Oh, to return to the halcyon days of the late Cold War, when global catastrophe wasn't an economic metaphor or a reference to impending and seemingly unstoppable ecological extinction. Though the arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union had reached the level of competing over who could destroy everything and everybody on earth more times over, its logic was still seen as rational — that atomic armageddon could be staved off by ingenious applications of game theory — and thus under conscious human control.

The late Cold War wasn’t the Cuban missile crisis, those 13 days of storied brinkmanship at the edge of annihilation that taught the world about mutually assured destruction (MAD). Rather, the efficacy of the 1980s-era total-apocalypse bluff lay in its inconceivability: MAD was an apparently self-extinguishing threat, since an incinerated planet offers nothing to win or lose, nothing to fight or die for. But at the same time, the threat of following through with world-snuffing retaliatory strikes also needed to be credible enough that neither side would get the idea that nuclear war could be winnable. MAD doctrine insists that the scale matters more than the items weighed.

But for ordinary civilians, the prospect of all-out nuclear war was so staggering that it became an exercise in sublimity to try to conceive of it. Thinking about nuclear war was like contemplating the nature of God or the conditions before the Big Bang. One had to laugh at the preposterousness of it all (though Sting earnestly wondered whether or not Russians hated children). Doomsday fatigue set in among the free-world populations threatened with extinction. In the Cold War's twilight years, the terror implicit in nuclear paradoxes lapsed into snickering incredulity, despite the mad proliferation characteristic of MAD. I see your Topol missile and raise it one MX.

So thoroughly did materiel crowd the landscape that finally the Reagan administration decided to take their game to space with the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), or "Star Wars." This was a grab-bag of offensive and defensive weaponry parked in orbit around earth that would give the U.S. the upper hand in the arms race. Sold as messianic deliverance from potential planetary immolation, the $30 billion project would let scientists "give us the means of rendering these nuclear weapons impotent and obsolete," President Reagan declared in a speech on March 23, 1983. With SDI, the Reagan administration sought a loophole in the iron laws of MAD, but by promising to make the Cold War game of world destruction seem winnable, SDI also offered a stronger temptation to actually play it. It was the limit case of MAD-induced madness.

SDI's promise of permanent supremacy was also its gravest threat. People had to fear that SDI was unworkable, and worse, that it might work after all.

***

To treat this Cold War Weltschmerz, Hollywood in its wisdom produced Spies Like Us, a 1985 Chevy Chase–Dan Ackroyd comedy in which the failure of an SDI-like system leads to the end of U.S.-Soviet hostilities. The movie fuses the winking-con-man spirit and the fraught buddy-movie homosociality of Bob Hope and Bing Crosby's Road pictures with the tense absurdism of Dr. Strangelove. These elements proved more compatible than they might at first appear. It turns out the half-assed insouciance of the performers and the tossed-off, seemingly improvised script aptly counterpoint the high-stakes deception of MAD. Both defy you to suspend your disbelief. Thus Chevy Chase's near contemptuous superiority to the diegesis parallels MAD's steely insanity; neither lets you accept the situation as it's given. Insisting that a scene be taken seriously becomes indistinguishable from refusing to: After all, no realistic scenario is imaginable in which Chevy Chase will pass for a spy, or in which thermonuclear weapons could actually be launched. Implausibility is the secret to the effectiveness of both.

Spies Like Us isn't merely a sendup/enactment of Cold War deterrence logic. It also anticipates the zeitgeist of the neoliberal new world order that would install itself as the end of history after the Berlin Wall fell

David Hasselhoff lookin' for freedom at the Berlin Wall

David Hasselhoff lookin' for freedom at the Berlin Wall

In Spies Like Us, communism is a joke, consumer desire is becoming universal, and the world is happily full of shirkers and impostors because nothing is worth the effort of genuine belief. The film shows the American pop-culture hegemony creeping in at the edges of the Iron Curtain, doing its leveling work: a Russian missile crew dances to the Bar-Kays' "Soulfinger"; a Doctor Zhivago poster hangs in a Soviet interrogation hut; KGB agents dress as iconic 1980s preppies.

Most tellingly, the movie ends with Russian negotiators competing against their American counterparts at Trivial Pursuit to decide the world's fate. Having a mastery of entertainment-biz effluvia will be the most important form of knowledge in the post-Cold War dispensation.

None of the film's characters have anything like firm ideological conviction. Political antagonism has lost its force and been reduced to kubuki theater and make-work for the government functionaries that Spies Like Us is preoccupied with — and who will, it suggests, inherit the free world.

Chase plays Emmett Fitz-Hume, a government flack who owes his job to nepotism. When we first meet him, he sits at a desk in an open-plan office, wearing headphones and watching a Ronald Reagan musical on a small color TV. Ostensibly part of a workplace team but explicitly indifferent to what's happening around him, Fitz-Hume exemplifies what would become a familiar type in the cubicle 1990s, a proto-cognitarian.

When work pressure bears on him, he resorts to double-talk, ingenious improvisation, and downright fakery. Fast-talking, pragmatic and morally lubricious, Fitz-Hume accepts the obsolescence of meritocracy. When faced with that shibboleth of the meritocratic order, a civil-service exam, he figures the way to handle it is to sleep with his boss, and when that fails, to cheat by any means possible.

With Fitz-Hume's incompetence and indifference established, we are introduced to his flip-side, Ackroyd's Austin Millbarge, toiling in the Pentagon basement. A thwarted overachiever and self-trained codebreaker, Millbarge is being exploited by his supervisor, who won't promote him and who forces him to take the same civil-service exam Fitz-Hume must take with no time to prepare. (Millbarge responds by impotently vowing not "to hook up the Disney Channel for free" for him.) With the hierarchy tilted against him and his conventional abilities, Millbarge has no route out of obscurity.

The juxtaposition of these two types tells us that as the Cold War bureaucracy stagnated, qualifications came to mean nothing if they weren't complemented with personal charm and an opportunistic streak. This point is underscored after Fitz-Hume and Millbarge's meet-cute in the exam room, when Fitz-Hume forces Millbarge from his meritocratic false consciousness. Fitz-Hume, who has arrived festooned with an eye-patch, sling, and fake arm all concealing crib notes, eventually turns to Millbarge, seated beside him, and holds up a question scrawled on his exam booklet: "What does KGB stand for?"

It's a resonant question, given that the exam room is immediately revealed to be laden with state-of-the-art surveillance devices that the exam monitor engages with the push of a button. Beyond the inanity of a civil service exam consisting of such trivia, the question offers itself to broader readings: Does the KGB "stand for" anything different from the CIA, which we subsequently learn is eager to send Millbarge and Fitz-Hume to their certain deaths as unknowing decoy spies? Does it meaningfully stand for Soviet supremacy, given the palpable ideological exhaustion of the Andropov-Chernenko era?

Konstantin Chernenko, Soviet Politburo Chairman in 1985

Konstantin Chernenko, Soviet Politburo Chairman in 1985As the title of the movie suggests, KGB are just "like us." The agency stands for the ubiquity of spies, the importance of surveillance to the sustenance of power, regardless of which political system makes use of it. It represents the excuse for a by-any-means-necessary ethos in anyone who can see beyond the ideological struggle to the world-weary cynicism it engenders.

Surveillance is also the catalyst that galvanizes Fitz-Hume and Millbarge's cooperation, calling it into being and making them useful to the state. After their exam-room antics, Millbarge and Fitz-Hume learn to their surprise that their buffoonery has captured the attention of a pair of elite spymasters who tell them they approve of their moxie. They have demonstrated the right stuff to become "GLG-20's," the cream of the spying elite. Self-taught, capable of spontaneous teamwork while disregarding mores and ethical limitations, they are, as their new bosses tell them, "people who are aggressive, people who know how to go after that little edge."

This resonates with the economic changes of the '80s and foretells of the emerging posthierarchical corporate structures of the informated 1990s. The Reagan administration broke the labor unions' power while wealth started to derived less from resources or finished goods than from tax loopholes, junk bonds, and debt-fueled "corporate raiding." The sun was setting on factory-based Fordism, which emphasized manufacture, and was starting to shine on post-Fordist production of information and affect, and service as commodity.

Spies Like Us dramatizes this transition, and the appearance of a new type of "social individual"

Of course, Fitz-Hume and Millbarge are actually being set up to be cannon fodder. The movie's premise requires us to be excited about this, as the characters themselves are. But the implicit critique remains salient. As post-Fordist workers, Fitz-Hume and Millbarge are built to be replaceable parts, to be redundant, but always believe themselves uniquely chosen all along; their very efficiency lies in their idiocy. The same might be said of many creative-class cognitarians bedazzled by their own pseudo-empowerment.

***

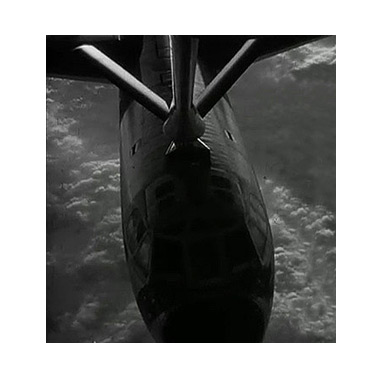

Under neoliberalism, skills and training are the precarious worker's problem, not the employer's. You must be shrewd enough to pick up what you can along the way through life without anyone specifically trying to teach you anything useful. The action of Spies Like Us hinges on this theme. Fitz-Hume and Millbarge's effectiveness as decoys depends on their never coming to realize that status, so they are forced to undergo a stunt-gag-laden training program which teaches them nothing remotely related to espionage. They endure an obstacle course to which has been added "the element of scorched earth," a live-fire dunk in a fetid bog, a drop from a tower while strapped in a junked airplane fuselage, an extreme-G centrifuge spin, a liberal dousing with flame throwers, a drag behind a speedboat, all for no apparent purpose save to satisfy the training-program colonel's (and the viewing audience's) sadistic impulses.

When Millbarge and Fitz-Hume tire of the torture and seek to resign, the colonel laconically replies, "Boys, it'd be a shame to have to kill you now." Millbarge interprets this for Fitz-Hume: "We're 'OIO,' " he explains. "Obligated involuntary officers." This OIO status is akin to Giorgio Agamben's

concept of homo sacer, a juridical designation with roots in Roman law that applies to individuals who may be killed without due process. Homo sacer denotes individuals who were "situated in a limit zone between life and death, inside and outside, in which they were no longer anything but bare life."According to Agamben, the state, in reserving unto itself the right to sentence a person to death, betrays that its sovereignty rests on the power to confer a fuller, more robust identity to individuals than that which falls to them by dint of existence. Thus individuals designed homo sacer — whether you call them the mob, the Lumpenproletariat, or the multitude — are necessary to determine the shape and contours of the state. Under neoliberalism, these outcasts are those who fail to produce value in the social factory through, as Virno writes, "the pure faculty of thought" and "the simple fact of having-a-language." Inasmuch as everyone speaks or thinks, they generate value that a state-supported capitalist can capture for private gain.

Once Fitz-Hume and Millbarge realize they have been designated OIOs — outcasts whose extralegal expendability sustains the capitalist order — they can redeem themselves only by becoming better neoliberal subjects, learning how to be productive through the process of scraping by and staying alive. As expendable decoys, they have had virtually nothing invested in their "spy training" beyond whatever it cost the state to torment them. Their delivery to the theater of operations (the Afghanistan-Pakistan border region) is a study in cost-cutting: They're dumped there inside a food-aid crate. With no support from the higher-ups or even knowledge of the real mission, Millbarge and Fitz-Hume nevertheless must manage to complete the objectives of the real spies purely as a consequence of their improvisational skills. A scene where they are forced to pretend to be surgeons epitomizes this: As they spout more and more egregious nonsense, a real surgeon questions their approach, to which Millbarge counters, "We mock what we don't understand" — a rich response that cuts both ways.

As with today's social-media free laborers — another set of semi-self-aware spies — their ordinary-schmuck amateurism turns out to be a difference-making advantage that allows them to achieve what professionals can't. Because they work without knowing what they are working on, they can produce untainted results and unexpected innovations without demanding a proprietary interest in them. The fact that they prevail against all adversity not only vindicates the ends-based moral reasoning for setting them up as sacrificial lambs but also neatly foretells of the proletarianization of erstwhile professional vocations.

***

The spirit of postideological optimism that pervades the closing moments of Spies Like Us only goes to show how thoroughly ideological the movie really is. No foundational truth rests at the heart of its story, which comes across as a parade of bluffs, ruses, and prevarications that set off an infinite regress of untruth. The Cold War's end will not put an end to spying but instead inaugurate a global system in which to make a living, everyone must always be in the process of deceiving to prove their worth.

This universal expectation of deception in the name of neoliberal productivity is lifted for only one scene in the movie. When Fitz-Hume and Millbarge, along with one of the real spies, reach their final objective, they find themselves at a Siberian mobile missile base, which they capture, subduing the two male and two female Soviet soldiers stationed to guard it. Only after completing their mission do Fitz-Hume and Millbarge know what it is: they launch the missile at the U.S. They don't know that they have been working for rogue elements in the American military to prove the efficacy of an SDI system (which fails); they believe instead that they have started World War III. Performing some quick calculations, Millbarge estimates that they have 42 minutes before the human race comes to an end.

The implication of the scene is clear: The only time we are really free is when the missiles are in the sky, on their way to obliterate everything, all possible consequences and disappointments. Lurking behind that is the idea that endless consumer desire is more dismal than actual apocalypse, in which (in fantasy, anyway) we can at least effortlessly get what we want for a glorious moment.

But rather than leave us with an orgiastic libidinal apotheosis, the film rescues reality. After their debauch, Millbarge figures out a way to divert the missile to detonate harmlessly in the outer reaches of space. The film then ends with one more deception. Fitz-Hume, speaking to the press, conjures the impression that delicate, high-pressure disarmament talks are going on, when really the negotiators — the heroes from the missile base — are simply canoodling and answering questions about Little Richard songs to divide the world's spoils.

The world-historical board-game match in this last scene offers a foretaste of a very different post–Cold War Elysium. With the nuclear stalemate broken, thanks to the shining example of international cooperation our heroes have modeled, we, along with the people of every nation can step boldly into a brighter future, one steeped in Coca-Cola, Big Mac secret sauce, and movies like Spies Like Us. A Trivial Pursuit, indeed.