America loves to watch its best and brightest come undone, but it’s never really understood them. Look at Jessie Spano.

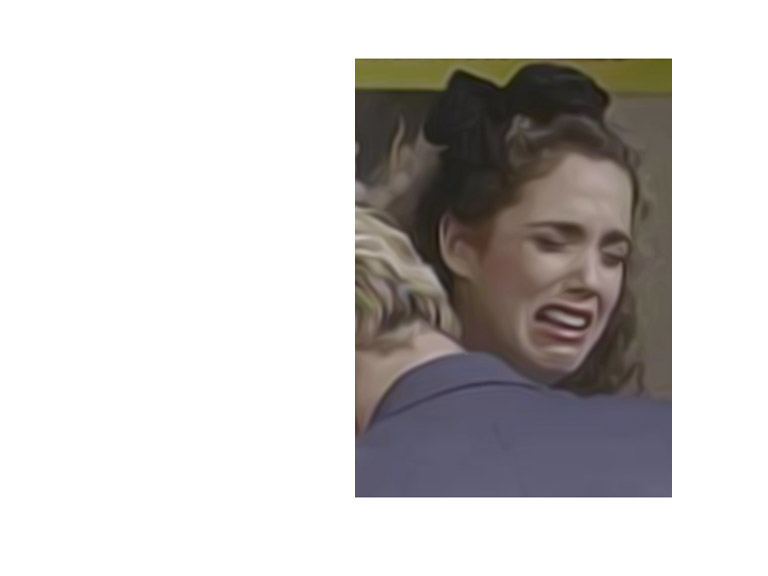

I’VE never subscribed to the notion that Jessie Spano’s (Elizabeth Berkley) breakdown in Saved By the Bell is a case of terrible acting. Prevailing wisdom suggests that the scene is a seriously misjudged attempt at portraying the vagaries of teenage depression, and history has confined it to the purgatory of parody. Through its endurance, this image has acquired a different meaning than its intended one. Jessie Spano’s caffeine pill breakdown is now evoked as a campy pastiche of 90s excess, a representation of everything we’d like to leave behind from that era. I’ve found this reaction to be callous and cold-hearted. Perhaps we’ve been unfair to her all along.

For those unfamiliar, a history lesson: In “Jessie’s Song”, the ninth episode of Saved by the Bell’s second season, Jessie has her eye on Stanford. Tall, athletic, and pretty, Jessie is a serial overachiever. Though she is the smartest girl in her class, she has astonishingly little aptitude for geometry. When she learns she got a C on her latest test before the midterm, she crumbles. “See? I’ll never get into Stanford!”

Over the course of the episode, Jessie will be drawn to various commitments, mere distractions from her from her monomaniacal quest to get into Stanford. To cope with these multiple stressors, Jessie develops a dependency on over-the-counter caffeine pills. This climaxes in a scene during which she collapses in a fit just before a big performance.

“I’ll let everyone down! I’ll never get into Stanford!” Jessie screams. She reaches for her pills. “I’m so excited, I’m so excited,” she muscles through the chorus. “I’m so…scared!”

Of the many Very Special Episodes that American television birthed, is there any as famous as this? None comes to mind. Berkley splays open Jessie’s anxieties in this scene; it’s a bit of committed, earnest acting that lacks any polish. I am reminded of what film critic Adam Nayman observed of Berkley’s widely-pilloried performance in Showgirls

America didn’t really “get” Jessie Spano in her time, and, 25 years later, it still doesn’t. Nor does it really get teenagers like her. This became abundantly clear to me during my four years at Stanford, the school of Jessie’s dreams, at the beginning of this decade. The university was riding a wave of fantastic PR -- a dwindling admission rate, a geographical proximity to Silicon Valley that was bafflingly framed as an attraction -- offset by reports of what was going on just outside our palatial campus. Every few years, some students at Henry M. Gunn High School and Palo Alto High School harbor suicidal ideations. A few act on those by jumping in front of incoming Caltrains. In the 2009 - 2010 school year, five students committed suicide within the span of nine months, followed by that of another recent grad in 2011; in the 2014-15 school year, four took their own lives. This epidemic has transmogrified into an object of national spectacle. Outlets ranging from San Francisco Magazine to VICE to the New York Times have all asked the same question -- what’s killing the ambitious, talented kids of Palo Alto?

The most widely-trafficked of these stories came last December, when the Atlantic published a cover story penned by Stanford alum Hanna Rosin provocatively entitled “The Silicon Valley Suicides.” The mere title suggested that the brightest minds in Silicon Valley, so-called incubator for tomorrow’s thought leaders, were dying before the age at which they could change the world. The piece was the kind of magazine journalism that ricochets across social streams, attached to trite qualifiers like “sensitive,” “thorough,” and “important.”

Rosin spent the perimeter of her eight-thousand word piece interviewing students, parents, and other community members about the young teens they know who’ve committed suicide, grasping for overarching trends to answer the question that inevitably follows suicide: why? She posed a few possibilities: is it Silicon Valley? Tiger moms? The teachers? Stanford? Some highly-combustible combination of all of the above factors? Rosin didn’t know. As Rosin reported out the story, she discovered the basic truth of suicide: it defies easy causality. “I found out that you can never really know why someone takes their own life,” Rosin commented in an interview after the story’s publication. “The closer I got to it, the further away it was.”

Rosin’s piece was artfully constructed, as any piece of prestige magazine journalism should be, yet it seemed to present a basic fact -- that suicide is never monocausal -- as a groundbreaking truth. This recalls what one Palo Alto student wrote: ”The story is honest and true, and Rosin provides a clear overview of what has happened in Palo Alto, but it offers little that is new, at least not for someone who lived it. Ultimately the article provides a bird’s eye view of a community that deserves much more than that.” Other readers from Palo Alto agreed. Something felt disingenuous, if not downright irresponsible, about a journalist from a national publication parachuting into a place beset with tragedy and scavenging for easy answers, packaging a community’s anguish in purple prose.

An article like Rosin’s is engineered to exist for the gratification of its readership, inviting them to gawk as spectators at the pain of bright young American minds without really parsing the contours of that pain. This falseness comes through in the piece’s last line: “They’re kids, so they can still forget,” the piece closes as she observes Palo Alto High students. The deployment of such a rhetorical tactic reveals Rosin’s pretense of empathy as mere posturing. She relies on a sense of comfortable distance, a reassurance that the experience of these “kids” is far from her own. And the adults reading this story could, too, be assured that they didn’t have to see themselves reflected in these kids -- these teens were of a new, troubled, generation.

The implication of Rosin’s read was that we outgrow these depressive spells with age, especially once we escape those pressurized shackles of high school. I only wish this were true. I stepped onto Stanford’s campus a lot like Jessie Spano -- desperate to succeed, furious when I didn’t, stretching myself exceedingly thin, stalwart in my refusal to “get help” (an abstract refrain I heard constantly from those who’d never confronted depression). By then, Stanford had rather deliberately groomed its image as the dream institution of many young Americans. University figureheads force-fed the koolaid to us from the onset of our time there. This distortion made this impossible to believe that anyone would not want to go there. We were living out Jessie Spano’s unfulfilled dreams.

Such an environment didn’t exactly do wonders for those of us who’d stepped onto that campus with histories of depression. After a few months, I -- along with many others at Stanford -- found myself achingly depressed, just as I’d been in middle and high school before then. Yet I entertained a myth of mental stability regardless, agitated by a surrounding culture that aggressively insisted upon its particular brand of sunny, West Coast appeal. This mirage gave way to something more sinister on occasion. Some students I knew committed suicide, yet these deaths weren’t acknowledged as such by an administration hungry to maintain its sacrosanct image. A few more attempted it. Many of us contemplated it.

I thought of Jessie’s breakdown often in those years. Watching that episode again, I’d feel a pang of ugly recognition rather than any desire to laugh; it resembled the fits and furies not only of my past life as an ambitious high schooler, but my present day one, too. I only then began to realize that what I’d experienced before in high school had now simply been transposed onto a new context. It took me some time to come to terms with the fact that these feelings wouldn’t go away -- that a depressed high schooler becomes a depressed college student, and that person will age into a depressed adult. These symptoms stay constant even if the context shapeshifts and time passes.

The pernicious myth about depression, propagated by Rosin’s article, is that its burden lightens with time. Saved by the Bell, too, is a kind of show that actively furthers this myth: Jessie barely speaks of the caffeine pill incident again, and mention of it just pops up for thirty seconds in a “don’t do drugs” episode, wherein Jessie recounts that she was addicted to pills. Berkley’s eyes dim in that moment, her body language hollows out, and the register of her voice drops, but the show isn’t necessarily attuned to what Berkley’s trying to do here. The show simply writes it into Jessie’s history -- something she was ashamed of, outgrew, and left behind. She ends up going to Columbia, while her fellow Bayside classmates waste away at a fictional California university. We’re led to believe that depression was just a phase.

Imagine if Jessie had inhabited a different televisual universe, one more aesthetically somber—say, a My So-Called Life or Freaks and Geeks. Would America have taken her desperation more seriously? And what would have become of her -- would she have eventually killed herself? A series like Saved by the Bell is straight out of the American playbook of sitcom fantasy, which is probably why Jessie’s breakdown still registers as so jarring. That scene spoke against every other aspect of Saved by the Bell, a show that provided a bizarrely anodyne depiction of American teenagedom, replete with its United Colors of Benetton cast who never spoke of race. Nothing was sanitized about Jessie Spano in this episode. What Berkley gave was a rupture to the hunky-dory world of the show, a raw and unfiltered and confessional scene. Against today’s climate, which has left us dumbstruck and befuddled as to why so many young Jessie Spanos are killing themselves, shouldn’t we understand this scene better than ever? We are now, as a country, engaging in a kind of performative sympathy, looking at Palo Alto with misty eyes and heavy hearts and mealy-mouthed proclamations of empathy on social media, yet this scene hasn’t been a beneficiary of this.

In spite of its seeming urgency, it seems unlikely that Jessie’s breakdown will undergo a critical reevaluation that puts it alongside the medium’s great depictions of mania. But I maintain that the image of Jessie Spano is predictive -- not only in the way it depicts how a generation would continue to cry for help, but also in the way those cries would always be misunderstood by the spectators looking upon them. Indeed, America likes its depictions of teenage depression soft and sanitized, like Rosin’s piece. America recoils at depictions of the grotesqueness of depression’s extremities, anything that carries the suggestion that this illness is more than just a mood we’ll outgrow. The truth is a bit harder for America to swallow, but it’s one that Berkley -- with her gnawing, unmodulated bid to keep singing even though she couldn’t -- understood better than America ever will.