When I read an article reporting that Richard Masato Aoki had been an FBI informant on August 20th, I was, to put it mildly, upset by the allegation.

Like everyone else, I have to weigh the evidence and the sources claiming Aoki, a Japanese American involved in radical activism during the 1960s, including the Black Panther Party (BPP), worked with the FBI. Why were so many of us so devastated by the claim and apparently blind-sided by the possibility?I had never wondered if Aoki could have been an informant. I just took his commitment to social justice, and specifically Black liberation, to be true. The reactions on social media and on the internet suggested I was not alone. Many people, notably progressive people of color, expressed disbelief. Those who had worked closely with Aoki, including the executor of his estate, some he politically mentored, and Black Panther Bobby Seale, were reportedly surprised by the news. Working through my sadness at such a possibility and noting the level of grief expressed on social media, I had to wonder, what had some of us missed? And why hadn't we speculated out loud about Aoki possibly being an informant to the degree we do African American political veterans? Was there something about what Aoki represented to us as progressive POC—especially us who are Asian American leftists—that made many of us refrain from a healthy skepticism of Aoki and indeed, any person whose celebrity rests largely on racial border crossing?

I am not trying to cast aspersions on interracial coalition building nor suggest that Asian Americans in particular should be met with political suspicion if we work across racial lines. But the degree of disbelief expressed at specifically Aoki possibly being an informant is notable as is some commentators’ perverse defense of him—and in the process, FBI informants in general. Some have argued that we need to remember that politics is “complicated” and that even if evidence were to convince us that Aoki was working for the FBI, it would not tarnish his legacy or symbolic significance. For example, Fred Ho, a well-known figure of “Afro-Asian solidarity” who had been a close friend of Aoki and a publisher of some of his work, flat out says, “If Aoki was an agent, so what? He surely was a piss-poor one because what he contributed to the movement is enormously greater than anything he could have detracted or derailed.” Although Aoki could be a victim of “snitch jacketing 2.0,” I am concerned with how willing some are to forgive him if he was an informant. Although an informant may differ from other FBI infiltrators such as provocateurs, that person would have to be willing to support and watch the FBI destabilize people and organizations. And I am bothered that some people are more concerned with preserving their individual relationships to Aoki—whether personal or symbolic—than to prioritize the people whose lives he would have negatively affected if he was an informant. But as an Asian American devastated by the charge against Aoki, I understand the emotional struggle involved in reconsidering his legacy.

I suspect that this struggle to reevaluate Aoki’s legacy is more about how we want to see him than what we actually (thought we) knew about him. Many of us feeling such grief at the allegation probably never spent any quality time with Aoki or even met him before he committed suicide in 2009. Indeed, a good portion of us probably knew little about his biography or what he had been involved in besides the BPP as the complete works on Aoki have only just become available through a 2009 documentary and a book published just this spring. With the exception of his ideas included in a collection edited by Ho, Aoki has received relatively limited attention in the growing body of work on Asian American anti-imperialism and Yellow Power compared to other figures such as Grace Lee Boggs and Yuri Kochiyama.

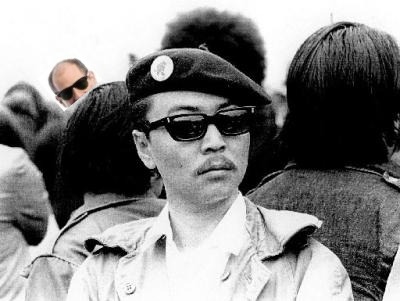

But as suggested in the iconic photograph of him sporting a black beret and sunglasses, Aoki was perceived by many of us who didn’t know him as cool, hip, and most importantly, politically down with the Black struggle. And yes, he was also unfortunately idolized for not being an “emasculated” (read nerdy or gay) Asian man—a homophobic and sexist preoccupation among many Asian Americans and our “allies.” And some of us liked that Aoki was known for providing guns and weapons training to the BPP. While there is afoot an intellectual effort to prove that the BPP was more than just about using guns, Aoki had passed a particular litmus test for non-Black allies of the Black struggle—a willingness to use guns or supply weapons in defense of Black people’s freedom and thus, purportedly be more willing to put one’s life on the line. Simply put, Aoki was, for some of us, our Asian American John Brown.

And yet Aoki was not John Brown. He was not white. He and his family had been incarcerated in an internment camp during WWII. As a youth he had been in a gang and in trouble with the law. His experiences with Blacks were not isolated to political organizing; he had grown up in West Oakland and images of Aoki during his youth show him hanging out with African Americans. Taken together, Aoki was a working-class Asian American man in a white supremacist society, whose biography makes for an even more seductive interracial coalition story. He was not the border crosser of the white anti-racist variety who used his dominant group member status and racial privilege to paternalistically help Blacks. Instead, for many of us, Aoki was an anti-model minority in the crudest sense: a working-class, socially rebellious Asian American who politically claimed his minority status and committed his entire adult life to radical activism.

Aoki, then, was the perfect hero for leftist Asian Americans as his biography spoke to two simultaneous desires that animate contemporary Asian American scholarship and activism. The first is being acknowledged by other people of color that we are racial minorities and not white or honorary whites. The second is proving to Blacks that we do not hate them or have structural power over them.

These are not new anxieties as scholarship and oral histories show that there was concern among Asian American activists in the 1960s and ‘70s about being perceived as a model minority—an assimilated, white identified, politically passive Asian American who believes in the American dream and rejects Blacks. But these twin anxieties remain and have become notable features of post-1992 Los Angeles Riots scholarship. As the riots pushed Black-Korean conflict—an already existing phenomenon in urban neighborhoods—into the national spotlight, an anxiety about Asian business owners being considered an occupying force in Black neighborhoods is often embedded in the Asian American scholarship even when the topic isn’t about Korean merchants. The interracial solidarity turn was a response to such political charges. While Blacks raised questions, not only to Asian Americans but to other POC, about who owns what, who controls what, who gets treated better, and why, many scholars, funders, publishers, and progressive activists responded by urging us to reclaim the hidden history of racial coalition between POC. This push for what I have described elsewhere as compulsory coalition fueled an interest in Black-Asian American solidarity beyond the political veterans of the 1960s and ‘70s and in turn, made Aoki, Boggs, and Kochiyama better known among younger members of the multiracial progressive left. In short, for Asian Americans Aoki represented our salvation. He represented what we consider the forgotten truths among progressives: that Asian Americans have suffered, that we’ve been racially targeted, that whites continue to treat us like shit, that we are not all rich or even middle-class, and that we were there and are here politically. And Aoki also represented for Asian Americans a relief from political indictment, of Black scrutiny of our racism or racial privilege.

I can’t help but think that this quest for salvation, institutionalized in academia and progressive media and activism, makes it difficult to interrogate coalition politics or the way it can be strategically used by the state to repress African Americans and radical movements. For example, consider how several scholars and activists have weighed in on this claim from M. Wesley Swearingen, an FBI agent who had investigated the Panthers during his long tenure with the bureau and whose commentary was included in the original article alleging Aoki was an informant: “Someone like Aoki is perfect to be in a Black Panther Party, because I understand he is Japanese…Hey, nobody is going to guess—he’s in the Black Panther Party; nobody is going to guess that he might be an informant.”

In a well-circulated lengthy Facebook note written the day the news broke, Asian American historian Scott Kurashige responds: “Who in their right mind would think that a Japanese American would be the perfect person to infiltrate the Panthers? You would immediately stick at [sic] out and arouse suspicion as to why you were there and where your loyalties really lay… Swearingen, on this specific point, clearly doesn’t know what he’s talking about, has no real knowledge of Aoki, and has never heard of the model minority (as in, you mean to tell me that at the same time the media is pushing the image of Japanese Americans as a model minority, the Black Panthers are going to think they are the model black militant?).

Despite taking issue with Kurashige’s commentary for a few reasons, Ho echoes his sentiment: “Swearingen only thinks that it is likely Aoki was an informer for the FBI because he was Japanese! How stupid! Would fierce Black nationalists accept someone more easily because he was Japanese? If that were so, there would have been more Asians in the Panthers!” And in her response to the allegation, Diane Fujino, author of the biography on Aoki, as well as one of Kochiyama, concludes, “more logically, Aoki’s racial difference made him stand out and aroused suspicion.”

Kurashige, Ho, and Fujino suggest that the spectacle of interracial coalition building—here, embodied in Aoki, one of the few Asian Americans getting to participate in the BPP (what Ho refers to as a group of “fierce Black nationalists” [a description of BPP ideology some would disagree with])—would be too obvious of an FBI or government strategy. In other words, we are to believe that racial border crossers cannot hide in plain sight or would be met with so much suspicion by Blacks that charlatans could be easily identified. There are several problems with this conclusion.

First, it presumes that people of other races have never been used to infiltrate organizations that focused on the plight of a specific racial group. Second, it presumes Blacks have a degree of political and material sovereignty in which they can actively exclude others—in this case, Aoki—wherein only sincere commitment from racial outsiders can break down the political barrier that Blacks presumably impose. Not to take away from African Americans’ attempts at self-determination, but Black organizations are likely the most structurally vulnerable to being infiltrated by members of other races as no other racial group has been as unmercifully demonized—by people of all political stripes—for wanting to have control over their community affairs and politics. Related, Blacks simply have less access to, or control over resources to put towards organizing, whether legal support, money, medical training, publishing opportunities, meeting space, or guns, and often must get them from others.

Third, Kurashige presumes that a so-called “model minority” would not be politically welcomed by the BPP. Perhaps. But why wouldn’t an “anti-model minority” be? Why wouldn’t Aoki’s biography and swagger—which becomes more interesting and spectacular when juxtaposed to the dominant image of Asian Americans as model minorities—be seductive to some African Americans at the time? If, for the most part, the white world and the Asian world don’t like politically left Asian Americans, African Americans tend to. Consider how we see Asian Americans today—including radical activists, scholars, spoken word artists, even Margaret Cho—get celebrated by non-Asian American progressives for not being “submissive” and more specifically, for working with Blacks and promoting Black-Asian solidarity. The latter is a condition of possibility for Aoki to even take on the depth of political symbolism among the range of people he has today as he, as well as Boggs and Kochiyama, are more known for their work with African Americans than their work with Asian Americans.

To argue that using Aoki would be too obvious an FBI tactic is to suggest that the state cannot exploit the very real desires for political solidarity among people of color in order to advance its agenda. But why couldn't it? There is evidence to suggest that by the time Aoki was an activist, the state already had. During WWII, the federal government championed racial liberalism and a multicultural American identity to neutralize political critique among African Americans and other non-whites as their dissension was considered a threat to national security and exploitable by axis powers, in particular Japan, who was promoting its own version of Black-Asian solidarity. As a Cold War strategy the White House sent Black jazz musicians, athletes, and journalists on State Department-sponsored events overseas, including to Africa, both to counteract claims among the decolonizing third world that the United States was racist and to gather intelligence as it was presumed third world peoples were more likely to be less suspicious of African Americans. When excluded from the 1955 Afro-Asian Conference, more affectionately known as Bandung for the Indonesian city in which it was held, the White House worked behind the scenes to get Black journalists there in order to gather intelligence while publicly feigning support for an all people of color gathering.

Given what we know, I have a difficult time believing that by the time Aoki worked with the BPP, the U.S. government wouldn’t consider exploiting hopes for third world solidarity among African Americans. While Aoki is treated as an exception because he worked with the Panthers—and to a degree he was as radical activism wasn’t as widespread among Asian Americans as some claim—the desire for third world solidarity was not isolated to the BPP. Nor were Black organizations as unwilling to work with other groups as some defenders of Aoki suggest when they imply that a “fierce Black nationalism” or suspicion of racial outsiders can ultimately protect African Americans from being infiltrated by non-Blacks. Whatever the case, the BPP was part of a longer Black radical tradition of looking to the third world and building alliances with other people of color. Different African Americans, including those whose influence was widespread and intergenerational and who experienced state surveillance, had expressed solidarity with other non-whites in notable ways. W.E.B. Du Bois traveled to China in the late 1950s and urged Africa to “know China.” Du Bois and Paul Robeson both sent letters of support to the Bandung Conference. After being deported in the mid-1950s from the United States for her political activism, which included opposing the Korean War, Claudia Jones organized Afro-Asian events in England. In 1960, Fidel Castro stayed at the Hotel Theresa in Harlem after the State Department worked behind the scenes to get his delegation blocked from another establishment. The ploy backfired; as Malcolm X put it, the Cuban leader “achieved a psychological coup over the U.S. State Department when it confined him to Manhattan, never dreaming that he’d stay uptown in Harlem and make such an impression among the Negroes.” Malcolm X referenced the Bandung Conference in his 1963 Detroit speech “Message to the Grassroots;” while he mistakenly gave the year of the gathering as 1954, he nevertheless championed what he saw as its ethos when he told his audience, “Despite their economic and political differences, they came together. All of them were black, brown, red, or yellow.” A year after he gave this speech in Detroit, Malcolm X met with a group of Japanese journalists in Kochiyama’s apartment to talk racial politics; as Kochiyama has described, the group wanted to meet Malcolm X more than any other American. In 1967, Muhammad Ali was convicted of draft evasion for refusing to fight in the Vietnam War, a gesture akin to Elijah Muhammad’s refusal, during WWII, to “take part in war and especially not on the side with the infidels,” which resulted in him being incarcerated. And of course, the BPP, as well as other Black activists and organizations, championed the victories and debated the ideas of Mao Tse Tung and Ho Chi Minh. In sum, there was a push for third world solidarity and some African Americans seemed more receptive to Asian Americans than some narratives of Aoki’s involvement in the BPP suggest, all of which would have been monitored by the U.S. government. Given that the state has been willing to take every single person and cause that matter to African Americans and strategically use their value to Black people for its own purpose, why wouldn’t it consider exploiting the desires for third world solidarity to infiltrate and destabilize organizations?

I don’t know if Aoki was an FBI informant and I don’t want him to have been one. Like others, notably the directors of the 2009 Aoki documentary who penned a statement on the matter, I reject any defense of informants and also want us to proceed with caution before accepting the claim that Aoki worked with the FBI. For those who knew Aoki, who worked with him, learned from him, and loved him, the task of coming to terms with his legacy is an unenviable one. And it will be difficult for the rest of us inspired by his story. But as we wrestle with what we know or want to know, we must also consider what politics, desires, and disavowals may have kept the possibility of Aoki as an informant an unasked question all this time.