The Hollywood witch’s real oath isn’t to the goddess or Satan—it’s to have and to hold

Twice now, Nicole Kidman has played a witch. First in Griffin Dunne’s 1998 adaptation of Alice Hoffman’s sister-sister toil-and-trouble novel, Practical Magic, and again in 2005, in Nora Ephron’s meta-movie-update of the beloved ’60s and ’70s sitcom, Bewitched, co-written with her sister, Delia. Unwieldy, both films hinge on gimmick, wane at the halfway mark, and include just enough disposable scenes as if they were made to be shortened for TV and air in the afternoon on the Oxygen Network.

Practical Magic is “liable to work as escapism for anyone who thinks Little Women has too much grit,” Janet Maslin wrote in her New York Times pan, categorizing it as a movie in which women discuss hand lotion. And Bewitched was the sort of big failure that gets footnoted as speedy sparring trivia in a Gilmore Girls episode. Still, with Kidman as their common denominator, these movies sketch a spectrum for Hollywood’s fixation with witches: At one end there’s the domestic witch wife who is proficient at brunch, screwball timing, and benign brouhaha. At the other end, the seductive sorceress misfit with a crew she considers her coven and an itch for revenge. One wears pink cardigans, paisley, and Lily Pulitzer; the other sees the world through oxblood-colored glasses. Ephron’s Bewitched and the ’90s cult hit The Craft bookend the scale (coincidently they share a producer, Douglas Wick) while The Witches of Eastwick, Practical Magic, and Hocus Pocus rank in ascending order.

In Kidman’s case, the disparities between her two roles—employing her powers to prank a man vs. to kill a man, for example—go on and on.

Bewitched is the story of Isabel Bigelow (Kidman), a witch who is desperate to quit the craft in favor of a normal life in Los Angeles. As it happens, she gets cast as Samantha (Elizabeth Montgomery’s role in the original show) in a television remake of the fantasy sitcom—essentially, a vehicle for failed actor and solipsist Jack Wyatt (Will Ferrell) to jump-start his career. Isabel’s charm—and spot-on Samantha nose twitch—outshines Jack, and soon the show belongs to her. The movie’s main conceit has less to do with magic powers so much as a question Ephron poses in the DVD’s directory commentary: “How powerful can you be in a relationship with a man and not lose his love?” In this case, the Hollywood workplace romantic comedy is appended: career, marriage, and coven. Witches too, struggle to have to all.

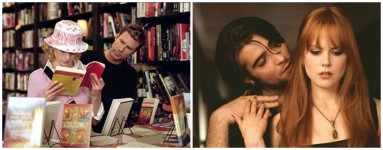

In this decidedly Ephron world, a meet-cute occurs in the Self-Help section of a bookstore, the men are for the most part total dolts, and L.A. landmarks are as adoringly mapped as the Upper West Side was in her 1998 rom-com You’ve Got Mail. Dipping and swooping on broom as we descend toward the city, Bewitched begins with an aerial grid that is distinctly L.A.: Hockney swimming pools and Ruscha parking lots. Later, we land on Isabel’s white-picket-fenced cottage in the Valley. Spreading her thumb and index finger away from each other as if enlarging content on a touchscreen, Isabel places a for rent sign outside the cottage, and just like that, it’s hers.

But as Ephron notes, Isabel is an addict. Each materialized thing, like the for rent sign or a beige VW bug that magically appears in Isabel’s new garage, generates guilt. She pays for her purchases at Bed Bath & Beyond by swiping a tarot card instead of a credit card, immediately shaking her head and vowing this is the last time. As Roger Ebert wrote in his review of the movie, Isabel’s one-last-time mien “makes witchcraft seem like a bad habit rather than a cosmic force.”

It would be interesting to see a director like Todd Solondz (Welcome to the Dollhouse, Palindromes) approach the character of an “addict witch.” In his world, comedy is an expression of darkness and suburban monotony is a façade for domestic disquiet. In a Solondz incarnation of Bewitched, Isabel’s near counterfeit pep and puckish smile, and her preference for overstuffed couches and fresh flowers, would imply pretense and, later, sickness. However in Ephron’s version, Isabel’s persona and Kidman’s performance of it seem entirely based on an impression of femininity. Witchcraft is a bag of hidden Oreos under the bed or that last cigarette. In one scene, dissatisfied at work, Isabel reassures her girlfriends that she is in fact, “Fine.” She adds, as if satirizing rom-com heroines, “Last night I ate three burritos and smashed every dish in my house.” In a Solondz film, nothing is lampoon. We would witness Isabel eat every last bite of that burrito on a half-broken plate.

But that’s a different movie. In this one, she quits witchcraft. First, she runs through a sudden rainstorm without summoning an umbrella—essentially, the cinematic mark of a free woman. Later at home, she continues her discovery of mere mortal life by popping a bag of popcorn. Nobody has ever looked more proud punching buttons on a microwave. Kidman’s naïve witch is largely a Meg Ryan pantomime: that sort of smiling, clownish stomp that makes her look like an optimist walking at a steep incline.

Ephron, whose sharply funny essays often draw attention to the general upkeep and regimen women are expected to follow, was obviously awake to the movie’s Twilight Zone tenor. “I want to have days when my hair is affected by the weather,” Isabel laments to her father (Michael Caine). Famously known for having her hair professionally blow-dried twice weekly, Ephron once advocated—with her patently punch-line wit—that it was “cheaper by far than psychoanalysis and much more uplifting.”

Positioned highest on Isabel’s pyramid of so-called ordinary, everyday life is finding a man who “needs” her “because he is a complete and total mess.” Reformed Witch Seeking Warlock Man Who (as Isabel puts it) “Seems Very Sweet and Unkept and Troubled.” For her, nothing is more desirable than quotidian tasks and compromises, and normal is personified by the couple who wheels past her in the towel aisle at Bed Bath debating paint colors.

Though far less peachy, Practical Magic is similarly preoccupied with the idea of finding a perfect man. (He can flip pancakes; he has one blue eye and one green eye.) Sisters Sally and Gillian Owens (Sandra Bullock and Kidman) are women whose powers come with a curse—the men they fall in love with are destined to die. Witchcraft, as the title suggests, is used rationally and rarely to subvert.

Whereas the women in Bewitched are meant to appear otherworldly (in a glossy-sheen sense of the word), the women in Practical Magic seem rooted in something more earthly. Or maybe that’s simply the effect of their home—an East Coast Victorian, picket-fenced no less, but overgrown and weatherworn. Sisters who whisper under bed sheets and ask questions like, “Do you forgive our mother?” are instinctively relatable.

Kidman as Gillian is the wild-child sorceress who climbs down trellises and runs away from home to live in California. She makes blood pacts, empties potions into cheap tequila, and likens falling in love to spinning really fast: You can’t see what’s happening to the people around you. You can’t see that you’re about to fall. She crashes Sally’s PTA meeting in a crop top, no bra, and belly chain, and announces to the classroom of uptight moms, “That’s right I’m back—hang on to your husbands, girls.”

Gillian is Hollywood’s Lilith Fair witch. She keeps her bedroom at a constant flickering glow, lighting candles as she sings along to Joni Mitchell or Stevie Nicks. (Isabel, of course, listens to Frank Sinatra’s “Witchcraft.”) Had Practical Magic been made in the past few years, Florence Welch would have scored it, maybe even starred.

Barefoot in black jeans, Gillian perches herself on counters or windowsills. She is a cat who walks down stairs as if balancing one paw in front of the other, narrowing her eyes as if readied to purr. In Bewitched, Kidman’s skin is fondant. In Practical Magic: porcelain. One witch’s cookie jar is another witch’s bell jar.

But more so, Gillian would never fall for a guy named Jack Wyatt. She would slice his name in two and pronounce it as if it were a question—Why-It? Instead, she meets Jimmy Angelov, whom she describes to Sally as having “this whole Dracula cowboy thing about him.” But Jimmy is abusive, and Sally, in her witchy synchronistic sister way, can sense Gillian is in trouble. She rescues her and accidentally kills Jimmy. “You have the worst taste in men,” Sally grumbles as they bury Jimmy’s body.

Dissatisfaction ties these two Kidman witches together. In both cases, the craft is a short cut or a revenge ploy, while a normal relationship with a man is the ultimate goal. Domesticity means safety for both of Kidman’s archetypal hetero witches. Neither one is too dangerous; one just chooses a Jimmy instead of a Jack. When Jimmy is killed, Gillian prays to God, begging his forgiveness. She promises to tame herself and have kids, and even attend PTA meetings. A woman’s powers, it would seem, are only good for one thing. The proper use of witchcraft, like the proper use of a woman’s sexuality, is to locate and snag the right guy.

In Ephron’s essay about the 1972 Democratic Convention in Miami where the National Women’s Political Caucus was purposed, as she puts it, to simply “put on a good show,” she typifies the feud between Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan by rivaling them as good witch and bad witch. “It is probably too easy to go on about the two of them this way: Betty as Wicked Witch of the West, Gloria as Ozma, Glinda, Dorothy – take your pick,” she says. “To talk this way ignores the subtleties, right? Gloria is not, after all, uninterested in power.” If the spectrum of witchcraft fits between Steinem and Friedan, there’s no wonder it collapses.

When the good witch and bad witch are one witch named Nicole, the moral coordinates take a back seat to the Hollywood narrative. The good witch shrewdly obtains what she wants, while shying away from too much power. (Isabel recoils when Jack—under the influence of hex—suggests to the network executives that she be promoted, “Make this woman a CEO of a multinational corporation!”) Meanwhile the bad witch is represented as sensitive, steering through life in a slip dress and caressing a black cat when she’s feeling extra vulnerable. Complexities do exist, but they serve only to shrink the witches down to size, small enough to fit in the home. Both movies end with images of domesticity: Gillian raking leaves and Isabel carrying boxes into her new house with her new hubby. Kidman’s witches aren’t humanized, they’re womanized. Any oath to goddess or devil is just training for the oath to have and to hold.