A conversation between two friends (or strangers).

Okwiri:

“Vote well, eh? We have to put our man inside Statehouse,” said a woman I had sat next to at the Easy Coach bus station, just three days to the elections.

I mumbled that I would not be voting.

The woman’s mouth fell. “Eh! How can you say such a thing loudly for people to hear? If Raila does not get inside Statehouse, me I will blame you.”

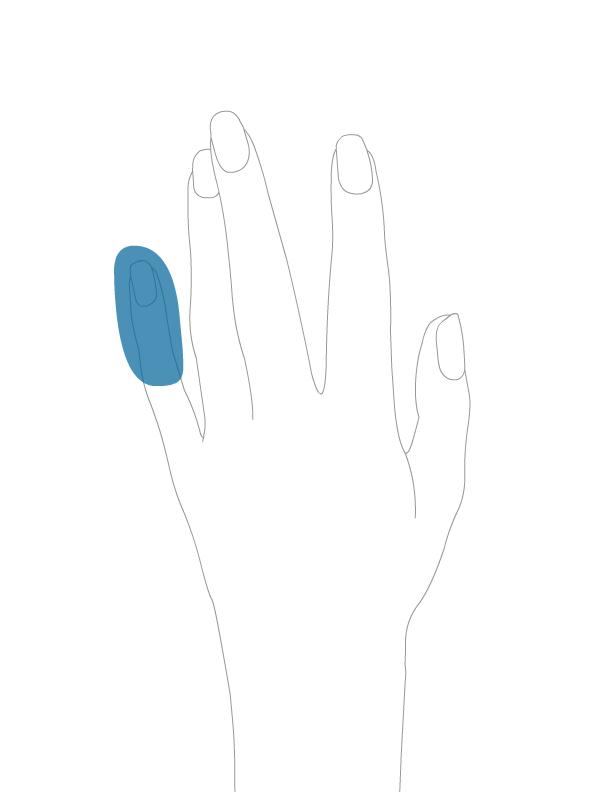

This was the constant refrain in the months before the elections, a time when you could not proclaim your reservations about the electoral process. On Twitter, voting cards had become popular avatars. Purple pinkies were a fashion statement.

The non-voter was a despicable person, deserving humiliation. A person like me lacked basic patriotism and had desecrated their ethnic legacy. My actions were outrageous. There was a call to national and ethnic ownership, and I was ignoring it.

I wanted to know why people voted. But the responses were just versions of the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) slogan: Your Vote, Your Future.

Many summoned the social contract to rebuke my unjustifiable apathy. And besides, they asserted, to vote was to acquire the right to complain, the moral authority. The non-voter was stuffing their mouth with gravel. They were required to acquiesce, henceforth, to go limp in the face of state aggression.

Kenne:

I am interested in the way people situated themselves for the elections, the kinds of material and ideological preparations they made before the elections, most of which were dependent on the election itself and its outcome. There was a lot of movement before the elections. Some people “going home” to vote, while others pre-emptively self-evicting themselves, in case 2007/2008 would happen again. The election conditioned people’s thinking. That’s why the woman at the bus station not only expected you to register but to vote for a certain person.

I refused to register or to vote for this reason, my refusal to participate in reducing the democratic process, from an expansive democracy to the act or event of voting.

Okwiri:

I did not register for a similar reason. It was not out of apathy, I shared in the concerns and anxieties that gripped Kenya. But the ruling elite, no matter what masks they wore, had interests more similar to each other than different. And for me, the prognosis was poor. There was little I could identify with, and even that little was flimsy. It was not enough for me to take part in empty ritual. I was very interested in the youth and women agendas, for example, but the political parties presented them in a way that was completely different from anything I had in mind. After looking at what the parties said about women and the youth, there was no way for me to select any of the aspirants. Had I chosen to vote, I would have been forced to use different criteria to make decisions on the political leadership. This was unacceptable.

You mentioned democracy, earlier. I have qualms about the nature of our democracy itself. It did not matter whether one went to the polls or not; the ruling class had its own agenda and we were there to make sure it was the legitimate agenda. I dispute the idea that the vote was the ultimate culmination of a citizen’s civic responsibilities, that after this event, one was required to do little else for five years.

Kenne:

The elections were also about the suspension of values and faculties of inquiry. Recently, Godwin Murunga wrote an article asking why Kenyan voters showed such outrage against members of parliament such a short while after voting them in. I think the outrage makes a lot of sense, because it’s detached from the election cycle. This moment is completely different from the election euphoria, from triumphant affirmations of a “mature” electorate.

Okwiri:

I’m reminded of the bombardment of peace infomercials on television, and of the massive billboards thanking Kenyans, after the elections, for keeping the peace. Those infomercials were a convenient way of making the election separate and distinct from anything else. Vote and go home, the authorities warned. I found this worrying, first in the suggestion that one ought to vote and then meekly accept whatever the outcome. Second, there is the suggestion that one ought to vote and then abdicate their civic duties for another five years. Civic duty is not reducible to a singular act. It is a deeper commitment to constant scrutiny of whether elected representatives are fulfilling their mandate.

Kenne:

Recently there was this association formed that sought to represent young people who found themselves disillusioned after the elections. They still faced the same problems they faced prior to the elections: poverty, unemployment, no inclusion by the governmental or corporate systems (what we here call “the private sector”). They had expected change. They had read the manifestos which elegantly catered to them. I felt detached from this group, even though I’m aware that I’ll easily form part of it once I graduate from law school. I’ll be subjected to an endless jumping through hoops while looking for employment and in the end deal with the disappointing fact that I need experience to get employment which I can’t get because I haven’t been employed!

I didn’t feel disillusioned because I didn’t invest in any political offer out there during the elections. I am interested in how this lack of disillusionment is a function of various privileges accorded to us: we attend university, our law degrees may be of value once we attain them because we are under a dispensation guided by a “constitution for lawyers,” as a friend put it.

Okwiri:

My disillusionment wasn’t from investing in political offers but from the dimming prospects any alternative future. I wasn’t convinced that much had changed over the last ten years, nor that much was about to change. True, the economy had grown, but the benefits have only gone to a few pockets. The inequalities were absurd. Historical injustices have never been addressed.

Recently, we have been othering each other, wallowing in an exclusionary nationalism in response to the Kenyan army’s incursion into Somalia. I’ve heard young people like myself call out members of ethnic communities of northern Kenya, accusing them of “taking over” Nairobi, expressing dread at having to “integrate with refugees.” I would have liked to see these issues engaged. Instead, they were replaced with more calls for a shared chauvinism and militarism. My lasting memory from the presidential debates is Paul Muite’s clenched fist, a lawyer and human rights activist promising to secure Kenya’s borders, with more militarism and a more hard-line stance on Migingo Island.

Kenne:

There is a piece on Gukira, on “queer disposability,” where he claims that politicians engage in homophobia not only because it is politically or rhetorically valuable to do so, but also for the purposes of “lubricating” anxieties or conflicts. I have been trying to find a place for myself in the discursive expanse that has been the post-election, and part of my resistance to voting was based on the failure to find a space that would have me and my “baggage” of nuances and idiosyncrasies. I think it is something that I and a lot of other queers shared. We were cowed during the elections, advised by LGBTIQ activists to lay low and keep away from trouble. This accounts for much of the apolitical positioning among queers, a cynical repudiation of that which has already marginalized us and rendered us violable. One would argue that women are disposable too. This similarity is very important for those of us who seek to create linkages outside our own identities.

Okwiri:

I am reminded not only of the hollow and token promises of inclusion, but also of the largely ignored constitutional threshold on gender parity. This went hand in hand with physical and psychological violence. The election season saw an unprecedented scale of violence against women aspirants, from instances of rape to attacks, threats and intimidation.

I spoke to women who expressed concerns about their safety, both prior and subsequent to the elections. Some of the violence they feared was domestic. One heard men gloat that there would be serious sanctions should their wives dare vote in any other manner than the men had stipulated.

Women also expressed concerns about the consequences of the elections. Any kind of post-election violence would include sexual violence against women. In the months preceding the elections, in fact, one read reports in the newspaper of women packing up and leaving urban areas for “home,” where they could get some semblance of protection against gender-based electoral violence. This last point reinforces what you spoke of earlier about getting ready for the elections, anticipating certain events and making certain choices.

Kenne:

These elections have been a lot of things. There has been the suggestion that its form and outcome can be explained in a set of facts or a singular narrative. Political elites corralled voters into ethnic blocs, the elections were determined by young and women voters, or that money and the promise of success determined who won the elections. The issues we’ve talked about here feature only marginally in how narratives about the elections are created.

This is how we, political nonconformists, radical feminists and queers, will survive the next five years, sustain and enlarge ourselves: by complicating simplistic singular narratives. By mounting critical resistance to established ways in which the Kenyan citizenry holds stake in the political economy.