The missile rushing over your head was processed through an Instagram filter just hours previously. As you see it pass out of sight behind the apartment block opposite some young conscript is preparing for video footage of it to be compressed and uploaded to YouTube before the hour is out. By nightfall tonight that explosion which just shook your neighborhood, in one of the most densely populated areas on earth, will have been liked over 8,000 times on Facebook. Welcome to Gaza City.

The mediated aesthetics of war have always tread a fine line between the banal and heroic, always used to justify, rightly or wrongly, the slaughter of young and old while always failing to really convey the profound and fleeting moment when a state chooses to end a human life, again and again and again a thousand times over. But just as war is the perennial driver of technological development, so it also remains the laboratory in which technological image production is really tested — the ability of one state or another to push representation to its limit and make you feel safe, happy, good about the flesh that is being torn from limb on your behalf. Propaganda aims to synthesise a community; a community that can protect, exclude, and hence is worth a sacrifice.

The current assault on Gaza is perhaps an early test of social media’s ability to understand and mediate war within, or on the borders of, a Western society. Here we see a newer aesthetic; a hybrid of networked technology, social media theory and a visual regime based around firmly entrenched, conservative branding techniques. We imagined futuristic (that is, contemporary) war to be realised along the lines of our hyperactive young fantasies, but perhaps we should have predicted that War 2.0 would look less like Starship Troopers than the early drafts of a footwear campaign or a coffee franchise loyalty-card scheme.

It shouldn’t be much of a surprise that the Israel Defence Forces are compelled to mobilize new social media strategies both as weapon and representation of war. The IDF’s history in the Occupied Territories has always been one of innovation, shifting topologies of conflict. For many years the IDF has schooled its officer class in continental philosophy, becoming pioneers of what might euphemistically be called “applied radical theory,” as Eyal Weizman explores in his investigation of Israel’s “architecture of occupation,” Hollow Land. As street-to-street combat became impossible for the IDF, they developed tactics of “infestation,” moving through the urban fabric by crashing through buildings, bringing the war from the street into the domestic sphere, “walking through walls.”

Similarly, as Israel removed occupying ground forces from Gaza in 2005, they were forced into implementing territorial control from the air, a process known as the “invisible occupation.” “The geography of occupation thus completed a 90-degree turn: the imaginary 'Orient' – the exotic object of colonization – was no longer beyond the horizon, but under the vertical tyranny of a western airborne civilization that remotely managed its most sophisticated and advanced technological platforms, sensors and munitions in the spaces above.” (Eyal Weizman, Hollow Land, pg 237, Verso 2007)

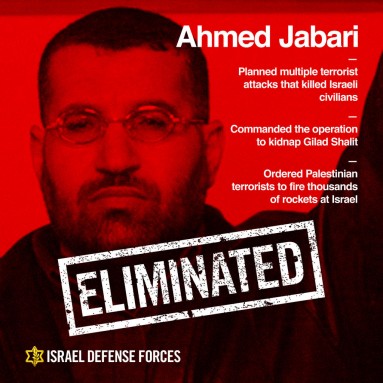

This transmutation of territorial control today enters a new topography, an extension of the historical "propaganda war": control of the networked space online. The IDF have run a comprehensive social media campaign from the first stages of the new assault, announcing the assassination of Hamas military chief Ahmed Jabari on Twitter, followed up by YouTube footage of his targeted killing within minutes. Then there were the step-by-step updates on the campaign, including statistics on rocket strikes, Israeli operations and “warnings” to Palestinian civilians to “stay away” from Hamas operatives for their own safety.

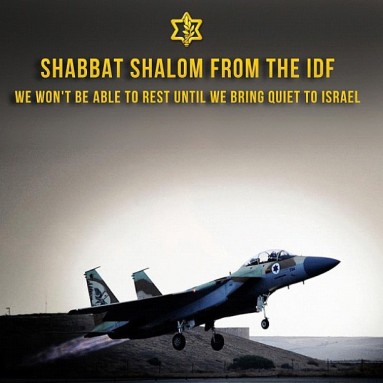

This integrated social media campaign is cross-platform, with accounts on sites from Twitter and Facebook to Pinterest and Instagram. The images posted on Instagram and the infographics released across platforms form the core of the IDF brand; with a coherent visual theme, and consistency with the brand narrative, they are reimagining an urban conflict and occupation on a new consumer scale.

Far from embracing ideas of a futuristic, dehumanising warfare, the instagrams of IDF, processed through the various “retro” and “soft-focus” filters, serve a dual purpose. The first purpose is that of historicization. Much as the hipstamatic literally filters the contemporary condition through the lens of the '60s and '70s, the use of “retro” filters removes the images of today’s IDF from their context within the current campaign of blockade and air assault and reframes them as part of the Israeli foundation story. These images are not to be judged alongside the grainy cameraphone footage of bodies being pulled from rubble, Hamas propaganda on forums and youtube channels, or Al-Jazeera coverage of Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh and Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi visiting wounded Palestinians in hospital. Instead the historic imagery invoked is of conflicts that have already been morally justified — the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, the Six-Day War and the Yom Kippur War, for example. The content is contextualized by the form into representing a historical and ethical argument, a national story as intuitively persuasive as apple-pie or Blitz Spirit.

The use of single-color screen has a similar effect on their repeated use on all images of Hamas leaders (ELIMINATED), rocket installations coloured blood-red etc. The figures are removed from their contemporary setting through being desaturated of their fleshy reality. The complex political history that complicates the relationship between the Israeli and Palestinian peoples is elided; their image is removed from conflict, from visual contestation, and is sucked into the narrative of the branding campaign. A visual filter evenly applied can work miracles, pulling together disparate, contested images into a single narrative.

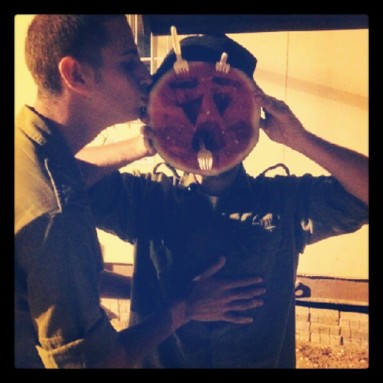

Secondly, the use of commercially available instagram filters replicates the visual culture favoured by much of its audience, producing images that slip easily into their feeds, naturalising the content. “These are the photos you would take if you served in the IDF,” the aesthetic says, “we are just like you, and these military decisions are the ones you would take, if you were in our situation.” They also step beyond this, including an aspirational aspect of a desirable lifestyle — impossibly handsome young troops, having fun on their downtime. This is a fighting force at play as imagined by Wolfgang Tillmans and BUTT magazine, a million miles from an occupying force. The images tap into the founding myth of the nation, as surely as Ralph Lauren campaigns exemplify the WASPy self-image of bourgeois America.

In producing an aesthetic equivalence with the brands whose advertising they emulate, in terms of perfect bodies, “timeless” subjects, etc., the IDF become as easily assimilable into consumers' personal-brand portfolio as those brands. Liking and sharing IDF visual material becomes no more controversial than sharing your favourite Nike campaign — not a matter of politics, let alone ethics, but just another part of the construction of your online persona. An analogue of this branding technique can be seen in the Obama campaign, in which a graphic style of desaturated images under colored screens, and strong, classic-modern sans-serif typefaces partnered with sentimental subject-matter is mirrored in the IDF campaign. The distance between the political image, the consumer image, and the personal profile image shrinks until one is indiscernible from the other.

Like many of the more advanced lifestyle brands, the IDF are shifting the focus of image production from their own staff and creative team toward their consumers: in this case, the troops, reservists, and supporters of the IDF. Content is aggregated from individuals and fed back into the social networks of the target audience. In many ways this is an advanced form of brand-management for a such a large institution; it shows a willingness to trust the audience, allowing them to define the brand, making IDFgram perhaps the first crowdsourced propaganda campaign for a state military but also one whose identity is ever more meshed with that of its troops and supporters, emulating fashion and lifestyle brands’ movement toward consumer-led campaigns.

Here the IDF becomes the avatar of a thoroughly Western consumer identity. The distance between our own lives and those of the men and women who fight in the IDF becomes ever shorter and more compressed; in collapsing this distance, the grainy and pixelated images of the Palestinian subject become more distant. This is the IDF campaign for control of the virtual environment, interjecting its brand identity into the slivers of human interaction online and thus attempting to occupy a greater portion of the market share for geopolitical allegiance. The IDF, however, isn’t a lifestyle brand but a component of the war machine; the images mediate not an online interaction but a slaughter of bodies, and the aestheticisation obscures the dynamics of the very real human cost of war. Online ideology plays itself out IRL. Gaza exists as meatspace devastated.