A dialogue on pop music’s prefiguration of the Occupy protests

By Max Fox and Malcolm Harris

Selective image redaction by Will Canine

Max (X): So why is Third Eye Blind’s “Occupy Wall Street” song so obviously a failure?

Mal (L): If it were opportunistic, it would have a better beat. It’s so earnest and guileless that it’s completely unappealing. It really shows how pointless endorsing Occupy Wall Street is as a gesture. You also can’t dance to it.

X: It reminds me of the woman at the union march at Foley Square calling “mic check” over the amplified sound system they obtained a permit for — what that’s supposed to overcome (no amplified sound) has already been accomplished. The signature of Occupy Everything is reappropriating spaces, which includes spaces in pop culture. It seems like Third Eye Blind is jumping into the spaces OWS has reappropriated here — and the occupiers have done fine getting the message out so far without Third Eye Blind’s weight.

“I notice that you got it

You notice that I want it

You know that I can take it”

— Britney Spears, “Till The World Ends”

L: It’s curious that in all the discussion of Occupy Everything, which has already reached the heights of meta-meta-commentary, we haven’t seen anything about pop culture besides who does or does not show up to the park or march. In the haze of “What could the protesters possibly want?” I side with Doug Rushkoff calling foul on the whole ignorance pantomime. The same industry that made a movie literally about murdering management—

X: “Don’t you want to kill your boss? Instead, watch Jennifer Aniston die a gruesome death in Horrible Bosses!”

L: They are shocked — shocked, I say! — when their target audience takes to the streets. Of course you know what we want, you’ve been selling it to us for years!

Aside from a few deservedly marginalized, Fed-obsessed Paulites, the crowds don’t have official policy goals. But they do have common affects. In a society where resistance is co-opted before it even comes into existence, shouldn’t we be able to better understand the protests and their near future through the way capital has already prepackaged them?

X: Yes, we should. If capital has co-opted it, then we finally know what it is! This should resolve the debates over what the right form of effective resistance has to be. Just because capital has brought a thing inside itself doesn’t mean that thing can’t be threatening to it. I mean, it contains labor within itself, it contains communism in itself. It is contradictory, and the condition of its own demise. These are supposedly the premises of a lot of Marxists.

Following Chris Chitty’s line of argument, we can read ads for movies like Horrible Bosses as simply revealing the fact that they express the conditions of their production, which unavoidably includes both resentful workers and smug one-percenters. Our encounters with commercial cultural products have probably the highest concentration of capital that we ever experience. In a 30-second TV spot, we see what $100 million looks like. So when the spot speaks, it’s no surprise that it speaks as capital. It barely matters what the content is; the voice of capital can’t help but overpower it.

But since capital is a relation between itself and its opposite, labor (or the revolutionary subject or whatever you’d like to say), it’s never totally clear whose voice is speaking in any given instance. Is it capital who’s saying, “This is our time”? Is it labor who’s singing, “Till the world ends”? It’s interesting also that this last line comes from Britney’s latest single, because the two contenders for her position as most profitable female pop singer, Gaga and Ke$ha, occupy the two voices, the one of capital singing to its opposite and the one of that opposite singing to capital. But in a bonus trick, what is sung is a sort of liar’s paradox. Neither can really say which one it is, because as dialectical poles, each voice depends on the other for its own identity. So we get Gaga saying more or less, “I’m not capital. Capital is a liar.”

L: And Ke$ha says “I am capital. Capital is a liar.” To search the underground for an earnest revolutionary soundtrack as people have before can’t possibly work now. Marketers rely on us to find something that hasn’t been sold yet so they can buy it. Capital is ahead of us at the moment, and if you spend a little time at Zuccotti Park it becomes clear that a lot of the occupiers are still parroting Christina Aguilera’s dreadlocked “You are beautiful/ In every single way.” But the content of popular music, what’s edgy enough to really capture public attention, has changed a lot since Christina topped the charts. Sorry Bob Dylan, you can’t compete with the Biebs.

At this point, I don’t think there are many images that some corporation can’t sell — maybe triumphant lethal violence against the police, as Evan Calder Williams suggests. Clearly violence against management isn’t off limits, otherwise Horrible Bosses couldn’t exist. If you do a close reading of almost any of these pop songs, especially the better ones, it’s amazing to see the fragments that stick out. The only feeling left for the music industry to sell back to us is crisis, and it makes for really great dance music.

You see this play out in the tastes on the radical left: The last explicitly anarchist party I went to promised “plenty of Ke$ha” on the Facebook invite without a bit of irony. Of course there’s also a kind of aphasia though, an inability for these songs to say what they’re about. Instead we have evocations of desires, specifically the bringing about of chaos, the control necessary to destroy control, running through the street, etc.

“I never thought that I could feel this power

I never thought that I could feel this free”

— Justin Bieber, “Never Say Never”

X: You could say they’re dancing around the issue. And yeah, a lot of those fragments happen to be nominally about dancing, but it’s pretty startling how much they sound like they’re singing about smashing shit up and taking over the streets, as joyfully as if it were a night at the clubs. This seems to be way closer to Occupy Everything’s aesthetic. Because it’s still beside or behind the point to talk about this or that thing that Occupy Everything says — the movement’s political content is still far more the affective experience of being together and taking over parks and bridges and streets.

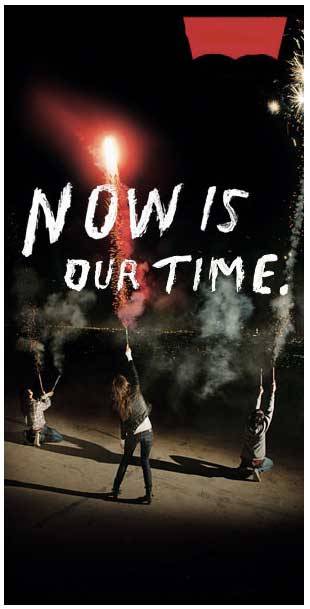

And this content is received like a language experienced by people who don’t speak it: “They’re just flapping their lips and dancing around, but they don’t seem to be saying anything!” But because we don’t even know what it is we’re doing in the longer term or even who we are, we talk about it as foreigners too: I just need to dance, we’re gonna dance all night, this town’s like a club, take the dance floor, etc., etc. Haters say, These are just dumb kids, and we say, Yep, we go dumb. And honestly, they still know exactly what we’re talking about (the world in crisis) because they made us make it and sold it back to us already. As if Levi’s doesn’t know its logo is a regicide. An upside-down crown, blood-red? They paid millions to come up with that.

“Tonight we’re going hard

Just like the world is ours

We’re tearing it apart”

— Ke$ha, “We R Who We R”

L: Insanity and craziness also come up a lot in these songs, which shouldn’t surprise us given the generational relationship with mental illness. Adults historically think kids are crazy, but ours were the first parents to administer psychoactive drugs to their children en masse. Half the teenagers in this country are officially “out of control” as far as the grownups in their lives are concerned, and the other half is buying their medication. We have come to see ourselves in the diagnoses, and since you can now label a virtual infant bipolar, kids born after 1985 have never understood themselves any other way. No wonder we don’t trust ourselves with mortgages, spouses, children, or state power: The crisis generation knows that it’s not stable. We’re “dynamite” “about to blow.”

X: “We are the crisis.” And this age split is absolutely there in the pop avatars themselves. Bieber, effectively commanding an army of the most technologically advanced tweens in human history, sings “I will never say never/ I will fight for forever” — the battle cry of an absolute nihilist if I’ve ever heard one.

L: “Nothing is enough!”

X: Another funny thing is how closely this split maps with who actually made most of these songs. Almost every single from the somewhat older guard of pop stars was written and produced by Max Martin (Britney, Christina, Backstreet Boys and N’Sync especially, but seriously, just take a look at his credits: It’s every pop song you remember from the past decade, as well as Gaga’s earlier hits), while almost every single by one of the younger ones was written by Dr. Luke, Martin’s protégé. The significance of this split is that the younger ones sing about taking over the city or club, impelled by the collapse of the future, and the older ones mock those who would be pretending to sing as them. Did you know that Ke$ha’s first phone call with Dr. Luke was disconnected as a joke by Paris Hilton while she was staying with Ke$ha’s family for an episode of The Simple Life, in which Ke$ha’s was the poor family Hilton condescended to spend time with?

“Victory’s within the mile

Almost there don’t give up now

Only thing that’s on my mind

Is who gonna to run this town tonight”

— Rihanna, feat. Jay-Z and Kanye West, “Run This Town”

L: The subject of a lot of these songs is sort of an amorphous, riotous “we” — it’s whoever is there and down to participate. It’s the same “we” I’ve used in this dialogue, and the one I end up using whenever I’m talking about a direct action. I get the feeling that we’re still a few years away from seeing the really threatening “we.” If there’s to be a revolution in our lifetime, it will be accomplished by 14-year-olds two years from now. True Beliebers.

But if this dialogue is for more than navel-gazing, then it has to be about exploding that potential now. Perhaps the thing we should remember about the London riots is that they forced Levi’s not to release a commercial it had ready that was basically riot porn. For a second, those two things were too close. If Hollywood could talk, it would probably admit that the box office on V for Vendetta wasn’t worth the hackers in Guy Fawkes masks. We as anticapitalists have to trouble the relationship established during the counterglobalization movement between cultural products and left resistance. What good is culture jamming when the giant subway ads already read “RAGE” with a circled A? I think there’s an answer, and it’s no longer about injecting new stuff or emphasizing implicit consequences. It’s about revealing and contextualizing what’s already very much there.

X: Yeah, and it would be pretty crazy if people ripped those ads off the wall and showed up to the march with them on sticks. Reappropriate the reappropriated! Another nice culture jam or whatever would be a remix or mashup of all these songs without the lines where they talk about dancing – what’s left would be expertly produced war cries. I would love to go on a march with Rihanna at my back reminding me “there’s only one thing on my mind/ who’s gonna run this town tonight.” Keeps you focused. If someone took these insurrectionary fragments and stitched them together into a dance megamix, we’d have a genuinely dangerous piece of music. Could even the most innocent of bystanders resist the pure form when they’ve been fed the adulterants for so long? Right now the levels are carefully balanced — a healthy dose of anarchic affect combined with typical capitalist tropes — but it’s within “our” power to knock them around.

“I want all of you tonight

Give me everything tonight

For all we know

We might not get tomorrow”

— Pitbull feat. Ne-Yo, Afrojack, and Nayer, “Give Me Everything”