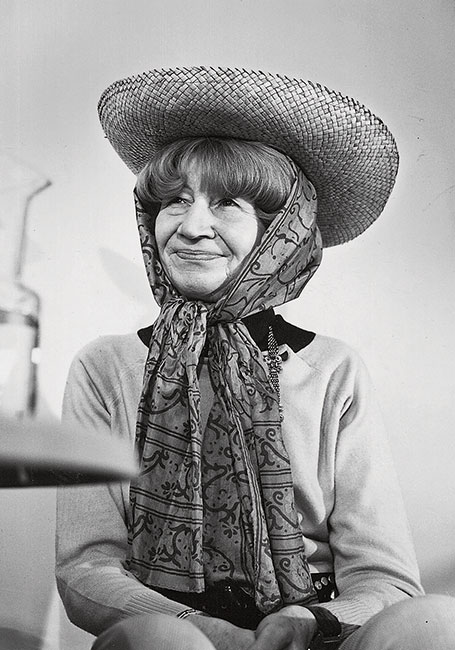

A bestseller in France at its first publication, Violette Leduc's autobiographical La bâtarde is an oft-overlooked classic of feminist literature. Famous for its frank discussions of sex and sexuality, its incredibly intricate characterizations, and its protagonist totally devoted to her own queer desire, the book never made a splash in the US, and was out of print for decades. It was rereleased by Dalkey Archives in 2003. The book has a foreword—equally little known—by Simone de Beauvoir, which we've republished below.

1976 Folio edition of La bâtarde

1969 Panther edition of La bâtarde

It is said that the unknown writer no longer exists; anyone can get his books published. That is exactly the trouble: mediocrity flourishes; the good seed is choked by the tares. Success depends, most of the time, on a stroke of luck. And yet even bad luck has its causes. Violette Leduc does not try to please; she doesn’t please; in fact, she alarms people. The titles of her books—L’Asphyxie, L’Affamée, Ravages—are the reverse of cheerful. Leafing through them, you glimpse a world full of sound and fury, where love often bears the name of hate, where a passion for life burst forth in cries of despair; a world laid waste by loneliness, which, seen from afar, looks arid. It is not in fact.

“I am a desert talking to myself,” Violette Leduc wrote to me once. I have encountered beauties beyond reckoning in deserts. And whoever speaks to us from the depths of his loneliness speaks to us of ourselves. Even the most worldly or the most active man alive has his dense thickets where no one ventures, not even himself, but which are there: the darkness of childhood, the failures, the self-denials, the sudden distress at a cloud on the sky. To catch sight suddenly of a landscape or a human being as they exist when we are absent: it is an impossible dream which we have all cherished. If we read La bâtarde it becomes real, or nearly so. A woman is descending into the most secret part of herself and telling us about all she finds there with an unflinching sincerity, as though there were no one listening.

“My case is not unique,” says Violette Leduc at the beginning of this narrative. No; but it is singular and significant. It demonstrates with exceptional clarity that a life is the reworking of a destiny by freedom.

Before we have read many pages, the author is already crushing us beneath the weight of the ineluctable pressures that formed her. Throughout the years of childhood, her mother inspired her with an irremediable sense of guilt: guilt for having been born, for having delicate health, for costing money, for being a woman and therefore condemned to the miseries of the feminine condition. She saw herself reflected in two hard, blue eyes: an offence in the human form. Her grandmother’s gentleness saved her from total destruction. It is to this influence that Violette Leduc owes the preservation of a vitality and a fundamental balance of mind that have prevented her, in the worst moments of her story, from going under. But the role of the “angel Fidéline” was only secondary; her grandmother died while Violette was still young. The Other was embodied in the mother with the eyes of steel. Crushed by this woman, the child attempted to annihilate herself completely. She idolized her; she engraved her mother’s law into her innermost self: fly from men. She set herself religiously to serve this woman, and presented to her own future to her as a gift. Her mother married; the little girl was shattered by this betrayal. From then on, she was afraid of all human consciousness because it had the power to turn her into a monster; of the presence of all human beings, because they all might dissolve into absence. She huddled down inside herself. Driven by the deceit practiced upon her, by her anguish, by her bitterness, she chose narcissism, egocentricity, loneliness.

“My ugliness will set me apart until I die,” writes Violette Leduc. This interpretation does not satisfy me. The woman depicted in La bâtarde interests dressmakers and dress designers – Lelong, Fath – to such an extent that they are glad to make her a present of their most daring creations. She inspires passion in Isabelle; in Hermine an ardent love that lasts for years; in Gabriel feelings sufficiently violent for him to marry her; in Maurice Sachs a definite and instinctive attraction. Her “big nose” seems to be no bar to either comradeship or friendship. If she sometimes makes people laugh it is not because of that; there is something unusual, something provocative about her dress, the way she does her hair, her whole physiognomy. People make fun of her to reassure themselves. Her physical ugliness has not controlled her destiny but merely symbolized it; she has simply found reasons in her mirror for feeling sorry for herself.

For, as she emerged from adolescence, she found herself caught in a diabolical trap. She loathed the loneliness which she had made her lot in life, and because she loathed it she plunged even deeper into it. She was neither a hermit nor an exile; her misfortune was that she never experienced a reciprocal relationship with anyone: either the other was an object for her or she made herself into an object for the other. Her powerlessness to communicate is apparent in the dialogue she writes: the people talk along lines that never cross; each has his own language which the other does not understand. Even in love, especially in love, any exchange is impossible, because Violette Leduc cannot accept a duality in which she sees lurking the threat of separation. Every break revives in an intolerable fashion the crisis experienced when she was fourteen: her mother’s marriage. “I don’t want people to leave me”: that is the leitmotif of Ravages. The couple must therefore be only one being. There are moments when Violette Leduc attempts to blot out her own personality, when she plays the game of masochism. But she has too much vigor and lucidity of mind to keep it up for long. It is she who will devour the one she loves.

Being jealous and possessive, she finds it hard to tolerate Hermine’s affection for her family, Gabriel’s relationship with his mother and sister and his friendships with men. She is insistent that her woman friend, once the day’s work is over, should devote every waking moment to her alone; Hermine cooks and sews for her, listens to her complaints, drowns with her in sensual pleasures, and gives way to her every caprice. Hermine demands nothing – except, when night comes, to be allowed to sleep. An insomniac herself, Violette rebels against this desertion. Later, she forbids it to Gabriel as well. “I hate people who sleep.” She shakes them, wakes them up, and forces them with tears or kisses to keep their eyes open. But Gabriel, less tractable than Hermine, claims the right to follow his profession and dispose of his free time as he pleases; every morning, when he tries to leave, Violette uses every means at her disposal to draw him back into their bed. She imputes with tyranny to her “insatiable insides.” In fact, what she desires is something quite different from sensual pleasure: it is possession. When she assuages Gabriel’s desire, when she receives him into her, he belongs to her; their oneness is a reality. As soon as he leaves her embrace, he is once more her old enemy: the other.

“Presence and absence, two identical mirages.” Absence is a torture: the anguished expectation of a presence. Presence itself is an interval between two absences: a torment. Violette Leduc hates her tormentors. They are each—as we all are—in collusion with themselves in ways that exclude her; and they also possess certain qualities she does not: she feels this as an attack upon herself. She envies Hermine her good health, her calm, her activity, her gaiety; she envies Gabriel because he is a man. She cannot undermine their privileges except by destroying their entire personalities; she attempts to do so.

“You want to destroy me,” says Gabriel. Yes. So as to remove the differences between them—and to avenge herself. “I was avenging myself because her presence was too perfect,” she says of Hermine. When they leave her, one after the other, she gives way to despair; and yet she has achieved her goal. Secretly, it is always her intent to shatter the relationship, the marriage. Because she craves failure. Because it is her own destruction she is aiming at. She is a “praying mantis devouring herself.” But she is also too healthy a person to work solely toward her own ruin. The truth is, she loses in order to lose and win at the same time. Her broken relationships are reconquests of herself.

Through the storms and through the calms she always keeps—and this is her strength—her instinct for self-preservation. She never gives herself entirely. After a few weeks of ardor, she makes short work of withdrawing herself from the range of Isabelle’s passion. At the beginning of her life with Hermine, she fights to go on working and providing for her own needs. Once conquered by the doctor, by her mother, by Hermine, her dependency weighs on her. She escapes from it thanks to her ambiguous and for a long time secret friendship with Gabriel. Once she has married him, she sets herself to destroy this bond by falling passionately in love with Maurice Sachs. When Sachs, after having gone as a volunteer worker to Hamburg, wants to return to the village where they had spent several months together, she refuses to help him do so. By then, transporting suitcases crammed with black market butter and legs of lamb into Paris with her own two hands, amassing a fortune, exhausted but triumphant, she is experiencing the heady delight of going beyond herself. Sachs would disturb the world over which she reigns, straight and proud as a cypress tree. “once he came back, I would shrink into the ground again.”

Others always frustrate her, wound her, humiliate her. When she grapples with the world, without outside help, when she works and succeeds, she is borne aloft by joy. The sniveling girl is also the woman traveler who, in Trésors à prendre, makes her way across the length and breadth of France, rucksack on her back, drunk with her discoveries and her own energy. A woman sufficient unto herself: this is the only image of herself that Violette Leduc can contemplate with pleasures. “I kept on till I had what I wanted: I existed at last.”

And yet she has the need to love. She must have someone to whom she can dedicate her bursts of joy, her melancholy moments, her enthusiasms. The ideal would be to dedicate herself to someone who will not encumber her with an actual presence, someone to whom she can give everything without anything really being taken. And so she cherishes the image of Fidéline—“My little apple who will keep forever"—miraculously embalmed in memory; and Isabelle too, now in the depths of the past a dazzling image for her idolatry. She invokes these figures, takes her solitary pleasure as she imagines them, prostrates herself before them. For Hermine, now absent and already lost, her heart beats in a panic of desire. She falls in love at sight with Maurice Sachs, and later on with two other homosexuals. The obstacle that separates them from her is so impassable that they might be a light-year away. In their company she “was consumed on the live coals of the impossible.” There is a sensation of pleasure to be had from an unsatisfied desire when it contains no hope. The woman in Laffamée whom Violette Leduc calls Madame is no less inaccessible. In La vieille fille et le mort, she pushed the fantasy of an unreciprocated love to a final extreme in which the other has been reduced to the passivity of a thing. Mlle. Clarisse, still unmarried at the age of fifty—not because men have neglected her but because she disdains them—goes into the café next to her grocery store one evening and finds an unknown man, dead. She lavishes attention and tenderness upon him, her effusions untrammeled by his presence; she talks to him and invents his answers for him. But the illusion fades: since he has received nothing, she has given nothing; he has not provided her with any warmth; she finds herself alone with a corpse. These love affairs at a distance ravage Violette Leduc as much as the reciprocated ones.

“You will never be satisfied,” Hermine tells her. Hermine destroys her by overwhelming her with gifts, Gabriel by withholding himself. The presence of her lovers drives her wild; their absence lays her waste. She herself gives us the key to this curse: “I came into the world, I vowed to entertain a passion for the impossible.” This passion took possession of her on the day when, betrayed by her mother, she took refuge with the phantom of her unknown father. This father had existed, and he was a myth; by entering the world she had entered into a legend: she had chosen the world of the imagination, which is one of the forms assumed by the impossible. He had been rich and of cultivated tastes; she relived these tastes, without any hope of satisfying them. Between the ages of twenty and thirty she coveted all the luxuries of Paris with a dizzying intensity: furniture dresses, jewels, expensive cars. But she made not the slightest effort to acquire these things. "What was it I wanted? To do nothing to have everything.” The dream of grandeur counted more than the grandeur itself. She lives off symbols. She transfigures the separate instants of her life by performing rites: the aperitif she takes into the basement with Hermine, the champagne she drinks with her mother, belong to an imaginary life. She is disguising herself when, to the sound of fantastic drums, she dresses in the eel-collared Schiaparelli suit; and her parade along the Paris boulevards is a parody.

And yet these sops to her desire do not bring satisfaction. From her peasant childhood she has retained the need to hold solid objects in her hands, to feel herself heavy on the ground, to perform real acts. To manufacture reality with imaginary materials: that is the prerogative of artists and writers. And toward this outlet from her dilemma she gradually makes her way.

In her relations with others he had simply taken her own destiny upon herself. When she begins to move in the direction of literature she gives it an unforeseen meaning of her own. Everything began the day she walked into a bookshop and asked for a book by Jules Romains. In her narrative she does not emphasize the importance of this fact, of which she quite obviously did not suspect the consequences at the time. An inattentive reader will perceive in her story only a succession of chance events. In fact it is a matter of a choice maintained and renewed over a period of fifteen years before finally bursting forth in a work of art.

As long as she continued to live in her mother’s shadow, Violette Leduc despised all books; she preferred to steal a cabbage from the back of a cart, to pick greens for her rabbits, to chatter, to live. From that day when she turned toward her father, books—which he had loved—continued to fascinate her. Solid, glossy, they held within their beautiful, shiny covers whole worlds where the impossible becomes possible. She bought and devoured Mort de quelqu’un. Romains. Duhamel. Gide. She was never to let them out of her life again. When she decided to take up a profession, she put an advertisement in the Bibliographie de France. She went to work at a publishing house, writing publicity releases and the like: she did not dare to think of writing books herself as yet, but she kept alive on a diet of famous names and faces. After her break with Hermine, she succeeded in getting work with a film producer; she read synopses, she made suggestions for treatments. It was thus through her own efforts that she altered the course of her existence and helped produce her apparently chance meeting with Maurice Sachs. She interested him: he appreciated her letters, he advised her to write. She began with short stories and articles of topical interest which were published in a women’s magazine. Later on, worn out by her continual spate of childhood reminiscences, he was to say to her: write them down, for heavens’ sake. The result was L’Asphyxie.

She realized immediately that literary creation could be a way of salvation for her. “I shall be a writer, I shall open my arms, I shall hug the fruit trees in them and give them to my sheet of paper.” Talking to someone who is dead, to people who are deaf, to things, is a grating game. A reader would provide that impossible synthesis of absence and presence. “This August day, reader, is a rose window glowing with heat. I make you a gift of it, it’s yours.” And the reader received this gift without disturbing the writer’s solitude. He listens to her as she talks aloud: he makes no answer, but he is a justification for her soliloquy.

Still, it’s necessary to have something to say. Fortunately, though in love with the impossible, Violette Leduc has never lost contact with the world; on the contrary, she clutches it to her as a means of filling the loneliness inside. Her unique situation safeguards her against prefabricated visions. Ricocheting from each failure back into nostalgia, she takes nothing for granted; she goes on tirelessly asking questions and recreating with words the discoveries she has made. And because she has so much to say, a wearied listener thrusts a pen into her hands.

Since she is obsessed with herself, all her works—with the exception of Les boutons dorés—are more or less autobiographical: reminiscences, a diary of a love affair, or rather of a loveless affair; a travel journal; a novel which transposes a certain period of her life; a novella introducing us to her fantasies; finally, La bâtarde, which summarizes and goes beyond her previous books.

The richness of her narratives comes less from the circumstances depicted than from the burning intensity of her memory: at each moment she is completely there through all the thickness of the years. Every woman she loves bring Isabelle to life again, herself the reincarnation of a young and idolized mother. The blue of Fidéline’s apron lights up every summer sky. Sometimes the writer makes a leap into the present; she invites us to sit beside her on the pine needles; this is her method of destroying time: the past takes on the colors of the here and now. A schoolgirl of fifty-five is writing down words in an exercise book. And sometimes, when her memories do not suffice to illumine her emotions, she whirls us off into strange flights of fancy; she exorcises the absences that tortures her with violent and lyrical phantasmagoria. Under its real-life covering, the dream life shows through, running like filigree through stories of the utmost simplicity.

She is her own principal heroine. But her protagonists exist intensely. “An excruciating pointillism of the emotions.” An inflection of the voice, a drawing together of the eyebrows, a silence, a sigh, everything is promise or rejection for this woman so passionately committed in her relationships with other people. The “excruciating” attention she pays to their slightest gestures is her good fortune as a writer. She brings their personalities alive for us with all their disturbing opacity and in the most minute detail. Her mother, flirtations and violent, imperious and conniving: Fidéline; Isabelle; Hermine; Gabriel; Sachs, as astonishing here as in his own books: it is impossible to forget them.

Because she is “never satisfied” she has always remained open to new experiences: any encounter can appease her hunger or at least distract her from it: everyone she meets is an object for her acute and attentive observation. She unmasks tragedies and farces concealed behind facades of apparent banality. In a few pages, in a few lines, she can bring to life the characters who have established a claim to her curiosity or her friendship: the old dressmaker from Albi who made dresses for Toulouse-Lautrec’s mother; the one-eyed hermit of Beaumes-de-Venise; Fernand, the dézingueur who makes away with sheep and bullocks on the quiet, on his head a fine top hat, between his teeth a rose. Moving, unusual, they take the same hold on our interest as they did on hers.

She is interested in people. She cares about things. Sartre tells in Les Mots how, brought up on Littré, things appeared to him as precarious embodiments of their names. For Violette Leduc, on the other hand, language is to be found in things, and the risk a writer runs is that of betraying them. “Don’t murder that warmth at the top of a tree. Things talk without your help, remember that: your voice will muffle them…The rosebush bows under the ecstasy of its roses: what is it you want to make it say?”

She decided nevertheless to write and capture their murmurs: “I shall bring the heart of each thing up to the surface.” When she is being ravaged by absence, she takes refuge among them: they are solid, they are real, and they have a voice. She sometimes falls in love with strange and beautiful objects; one year she came back from the South of France bringing two hundred pounds of dawn-colored stones with the imprints of fossils in them; another time it was pieces of wood, all in delicate tones of gray and twisted into visionary shapes. But her favorite companions are familiar objects: a box of matches, a kitchen range. She can extract the warmth, the softness, from a child’s sock. She inhales the odor of her poverty tenderly from her old rabbit-fur coat. She finds succor in a church chair, in a clock: “I clasped the back in my arms. I touched the polished wood. It feels so warm and friendly against my cheek…Clocks console me. The pendulum swings back and forth, outside happiness, outside unhappiness.” The night after her miscarriage she thought she was going to die, and hugged the little electric bulb hanging over her bed with genuine love. “Don’t leave me, dear little bulb. You’re so chubby. I’m going out with a cheek in the hollow of my hand, a shiny cheek that I am keeping warm.” Because she knows how to love them, she knows how to make us see them: no one before her had ever shown us those slightly tarnished flecks encrusted and glistening in the stairs of the Metro stations.

All of Violette Leduc’s books could be called L’Asphyxie. She feels stifled with Hermine in their little suburban home, and later on in Gabriel’s wretched apartment as well. This is the symbol of a deeper confinement: she wastes away inside the prison of her skin. But every now and then her robust health breaks forth; she tears down the partitions, she clears the horizon, she bursts out, she opens herself to nature, and the road unwinds beneath her feet. Aimless excursions, wanderings. Neither the grandiose nor the extraordinary have any attraction for her. She likes being in the Ile-de-France, in Normandy, meadows, paddocks, furrows, a land worked by man, with farms, orchards, houses, animals.

Often the wind, storms, night, a sky on fire, bring drama to this tranquility. Violette Leduc paints tortured landscapes which resemble those of Van Gogh. “The trees go through their crisis of despair.” But she can also describe the peace of autumns, the shy approach of spring, the silence of a sunken lane. Sometimes her slightly precious simplicity reminds of Jules Renard: “The sow is too naked, the sheep is overdressed.” But the art with which she colors sounds, or makes them visible, is hers and hers alone: “the sparkling cry of the lark.” We perceive abstractions through our sense when she evokes “the playfulness of the cow-parsley flowers…the anguished scent of fresh sawdust…the mystic vapor of flowering lavender.” There is nothing forced in her notations: the countryside is talking spontaneously about the men who cultivate and inhabit it. And through this countryside Violette Leduc is reconciled to those who live in it. She likes to wander through their villages, the open ones and those which are closed, shut in on themselves, but where each inhabitant knows the warmth of existing in community with all the others. In the bistros the peasants and the carters do not make her timid: she drinks, she is confident and gay, she wins their friendship.

All writers who tell us about themselves aspire to sincerity: each writer has his own voice, which resembles no other. I know of none more complete than Violette Leduc’s. Guilty, guilty, guilty: her mother’s voice is always stalking her. Despite that, thanks to that, no one can browbeat her. The faults that we impute to her can never be as grave as those she is charged with by her invisible tormenters. She spreads every last piece of evidence in the case before us so that we can deliver her from the evil she has not committed.

There is a considerable erotic content in her books; it is neither gratuitous nor deliberately sensational. She was conceived not by a man and woman but by two sexes. Her first awareness of herself, created by the constant harping of her mother, was of a condemned sex, threatened by all males. As a sequestered adolescent, she was stagnating in sullen self-love when Isabelle introduced her to sensual pleasure; she was shattered by this transfiguration of her body into a garden of delights. Doomed to what is called abnormal love, she became its champion. Furthermore, even though among the names she gives us for her solitude we sometimes find her using that of God, she is a firm materialist. She does not seek to impose her own ideas or her own image of herself on others. Any relations she enters into with them is of the flesh. Presence, for her, is the body; communication is only operative between bodies. To be fond of Fidéline means to bury oneself in her skirts; to be rejected by Sachs means to receive his “abstract” kisses; the outcome of self-love is onanism. Sensations are the truth of the emotions. Violette Leduc weeps, exults and trembles with her ovaries. She could tell us nothing about herself if she did not talk about them. She sees others through her desires: Hermine and her tranquil ardor; Gabriel’s ironic masochism; the pederasty of Maurice Sachs. Wherever she may chance to meet them, she is always interested in those who have reinvented sexuality for their own purposes: people like Catoplame, at the beginning of La bâtarde. Eroticism for her leads to no mysteries and is never cluttered up with a lot of nonsense. It is, nevertheless, the master key to the world; it is by its light that she discovers the city and the countryside, the density of the night, the fragility of the dawn, the cruelty in the mouths of pealing bells. In order to speak of it, she has forged herself a language devoid of sentimentality and vulgarity, which I find a remarkable achievement. It has alarmed her publishers however. They would not allow the account of her nights with Isabelle to appear in Ravages. There were rows of dots, here and there, replacing suppressed passages. La bâtarde they accepted in its entirety. The most daring episode depicts Violette and Hermine making love together before the eyes of a voyeur: it is narrated with a simplicity that disarms all censure. Violette Leduc’s discreet audacity is one of her most striking qualities, but one which has certainly done her a disservice: it shocks the Puritans, and the dirty-minded are left dissatisfied.

In these days, there is an abundance of sexual confessions. It is much rarer for a writer to speak frankly about money. Violette Leduc makes no secret of the importance it has for her: it too is a materialization of her relations with other people. As a child, she dreamed of going to work and giving money to her mother; once rejected, she gets her own back by filching it from her in small sums here and there. Gabriel places her on a pedestal when he empties his billfold for her; he pulls her down from it as soon as he becomes thrifty. One of the things that fascinates her most abut Sachs is his prodigality. She likes to beg: it is a way of getting back at the rich. Above all, she loves to earn money; it is an affirmation of herself, she exists. She hoards with passion; ever since her childhood, she has been haunted by the fear of going without, and she measures her own importance by the thickness of the bundles she pins under her skirt. In the comradely atmosphere of village bistros she will sometimes gaily pay for rounds of drinks. But she does not hide the fact that she is miserly: from natural caution, from egocentricity, from the grudge she bears the world. “Help my neighbor? Did anyone help me when I was dying of unhappiness?” Hardness, rapacity: she admits to them with amazing honesty.

She also acknowledges other petty traits such as we are usually careful to conceal. There were many embittered people who eased their rage against the world by taking advantage of France’s defeat: their first thought, after the Liberation, was to have it forgotten. Violet Leduc admits quite calmly that the Occupation gave her her chance and that she seized it with both hands. She did not find it unpleasant to see misfortune falling on other heads than her own for once; hired by a woman’s magazine but convinced of her own worthlessness, she dreaded the end of the war because it would mean that the “able” people would return and she would be fired. She neither excuses nor accuses herself: that’s how it was. She understands why and makes us understand too.

Yet she offers no extenuations. Most writers, when they confess to evil thoughts, manage to remove the sting from them by the very frankness of their admissions. She forces us to feel them with all their corrosive bitterness both in herself and in ourselves. She remains a faithful accomplice to her desires, to her rancor, to her petty traits. In this way she takes ours upon her too and delivers us from shame: no one is monstrous unless we are all so.

This audacity is a result of her moral candor. It is extremely rare for her to blame herself for anything or to produce any sort of defense. She doesn’t judge herself; she judges no one. She complains. She flies into rages against her mother, against Hermine, against Gabriel, against Sachs; she does not condemn them. Often she is tender, sometimes admiring; she is never indignant. Her guilt came to her from outside, without her being any more responsible for it than for the color of her hair; and so the words “good” and “bad” are empty ones for her. The things from which she suffered most—her “unforgivable” face, her mother’s marriage—are not listed as crimes. Inversely, anything that does not touch her personally leaves her indifferent. She calls the Germans “the enemy” in order to make it clear that this borrowed notion has remained quite foreign to her. She does not owe allegiance to any camp. She has no sense of the universal, no sense of simultaneity: she is there where she is, with the weight of her past upon her shoulders. She never cheats; she never yields to pretensions or bows to the conventions. Her scrupulous honesty has the value of a moral challenge.

In this world swept clear of moral categories, her sensibility is her only guide. Cured of her taste for luxury and social success, she takes her stand with determination by the side of the poor, of the friendless. So she is still faithful to the meager circumstances and undemanding joys of her childhood; and also to her life today, for after the triumphal black market years she found herself once more without a cent. She holds the destitution of Van Gogh, of the Curé d’Ars, in veneration. All forms of distress find an echo inside her: that of the abandoned, of the lost, of homeless children, of old people without children, of hoboes, of bums. She is desolated when—in Trésors à prendre, before the Algerian war—she sees the owner of a restaurant refusing to serve an Algerian carpet seller. Confronted with injustice, she immediately takes to part of the oppressed, of the exploited. They are her brothers, she recognizes herself in them. The people out on the fringes of society seem more real to her than the settled citizens who always behave according to their allotted roles. She prefers country pubs to elegant bars, a third class railroad compartment smelling of garlic and lilacs to the comfort of travelling first class. Her settings, her characters, belong to the world of ordinary people whom literature today usually passes over in silence.

Despite “the tears and the cries,” Violette Leduc’s books are “invigorating”—it is a word she loves—because of what I shall call her innocence in evil, and because they wrest so much richness from the shadows. Stifling rooms, hearts filled with grief—the truncated, gasping phrases have us by the throat: suddenly a great wind carries us away beneath an endless sky and gaiety runs beating through our veins. The cry of the lark sparkles over the bare plain. In the depths of despair we suddenly encounter a passion for living, and hate is only one of the names for love.

La bâtarde ends at the moment when the author has concluded the account of her childhood with which she began the book. Thus we have come full circle. The failure to relate to others has resulted in that privileged form of communication—a work of art. I hope I have persuaded the read to partake of it: he will find in it even more, much more, than I have promised.