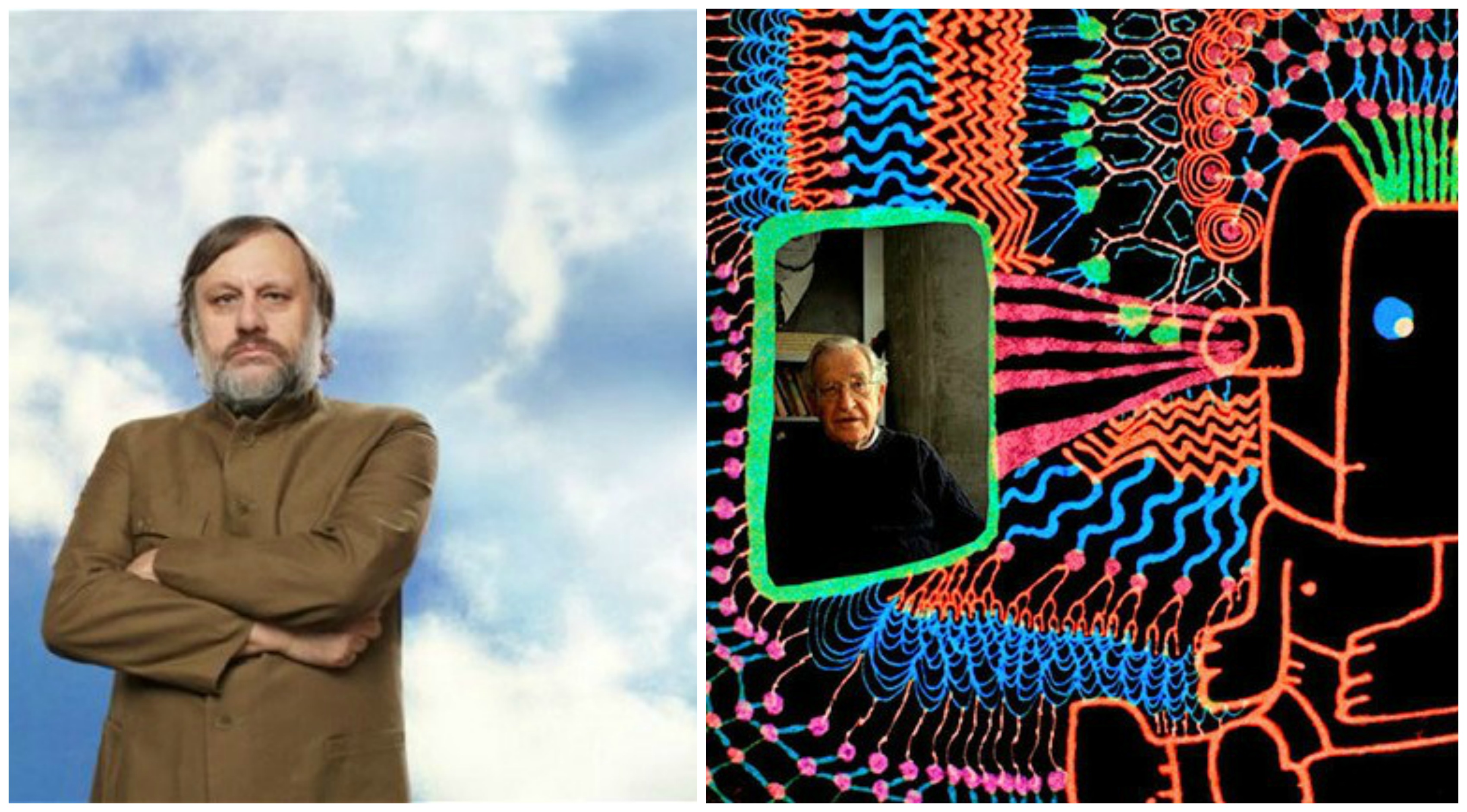

In the first installation of his film column Aspect Ratio, Brandon Harris looks at new movies featuring philosophers Slavoj Žižek and Noam Chomsky

The movies play tricks on us. Deception is the rule, suspension of disbelief the prerequisite. Whether Charlie Chaplin or Robert Flaherty, Michael Bay, or Steve James, it doesn’t matter who you are, let alone your intentions and budget and ideology. Some claim to simply glean moments from unobstructed reality. Others blow up things that look like bridges in places that look like New York using sophisticated computer-generated imagery and vast amounts of money, sums large enough to plug the municipal deficits of rust belt cities. Both the mythical unobstructed “reality” guy and the municipal deficits lady construct moments out of these various kinds of material that are equally artificial. Forget the box of the frame; once the cut and sound are introduced, reality is what we make it.

These tricks the cinema bequeaths us with are quite naturally bound up in the confluence of languages cinema has at its disposal here in the medium’s third century. Rhetorical and visual, narrative and purely sonic, movies clue us in, by their use of these many modes of communicative force bound up in the modern motion picture, how to think about them. What is up to you however; cinema is a plastic medium and it was designed to tell lies.

Those lies and a way to get at the truths they conceal, the very fragile nature of the truth, are the subject of The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology by Sophie Fiennes, sister of Ralph and poor Joe (how many moons ago was Shakespeare in Love?), about the psychoanalytic film criticism of the Slovenian philosopher and critic and celebrity Slavoj Žižek. Released theatrically at the beginning of the month, it is a follow up to her 2006 film A Pervert’s Guide to Cinema. The newer film follows a very similar formal strategy as the earlier one, intercutting between clips of classic films from Hollywood to Scandinavia to Soviet Russia, while Žižek appears intermittently on sets and in costumes drawn from the very movies he claims to mine hidden and often unintentional meanings from using his patented mix of Hegelian dialectics and Lacanian psychoanalysis.

That the latter has been a foundation element of psychoanalytic film criticism since the days of Christian Metz and Laura Mulvey doesn’t prevent Žižek's insights from feeling fresh, but one wonders if this is as much a reaction to his inimitable delivery style, all caustic tics and deadpan half-jokes tucked into unrelenting jargon, as it is to the revelatory nature of his discoveries within films such as James Cameron’s Titanic (to wit: “due to forces of class, the affair would have ended quite naturally a few weeks later, but ultimately the whole boat sinking thing provides a possibility to reinvigorate the shattered ego of an upper class girl by giving her lower class man meat”) or John Carpenter’s They Live, soon to be revived at IFC Center in the wake of its 25th anniversary, which offers a narrative that serves as a metaphor for Žižek's entire project of seeing ideology as a pervasive, all consuming aspect of our lives that we are often blinded to. If Roddy Roddy Piper offers you some glasses, take them.

The titles of Fiennes’s pair of Žižek films (which form a quartet of sorts when one also considers Astra Taylor’s 2005 documentary Žižek! and her 2009 effort Examined Life) indicate a subtle shift in emphasis from the first film to the second, seemingly suggesting the earlier film is more interested in film form while the latter concerns the constricting and freeing force that is ideology, in all its insidious forms, as represented in contemporary movies.

This is not such a clear distinction when watching them however. Perhaps the most preeminent superstar of contemporary left-wing thinkers, Žižek and his thought almost always circle back to sexuality and its repression, the political nature of gender relations and an attraction/repulsion impulse concerning “the other.” Both of Fiennes’s compelling but somewhat lugubrious movies with Žižek (each clocks in at over 130 minutes) follow suit, winding from discourse to discourse, often involving often thrilling and enlightening inter-textual readings of seemingly disparate films. But as bravura as those sequences can be, the picture never ponders any of the hidden possibilities it lays bare with any thoroughness and leaves the viewer more scattered and in awe than truly awakened to revolutionary possibilities.

Neither film, especially the newer one with its fancy HD photography and slightly pudgier, certainly more famous Žižek on display seems to have much tension within them between the author and subject. Fiennes clearly adores him and it’s hard to see why she wouldn’t I suppose, but Ideology could use a little friction, a clash of perspectives. It contains more speculation about the relationship of movies to contemporary events than the earlier work and embraces a more fully apocalyptic worldview perhaps, but in neither does Fiennes herself prove to be anything more than a conduit for a handsomely presented (and likely budgeted) reprisal of the incendiary readings of films Žižek publishes from time to time in the Guardian or New Statesmen. It’s a pity really. Watching her film, I kept thinking Žižek, a naturally charismatic performer, would be better suited opposite Fiennes’s brother and Daniel Craig as a Bond villain than locked into this series of occasionally rousing but ultimately canned explorations of the hidden modalities cinema manipulates us into accepting the nearly unendurable status quo of class domination with. But right there I’m outing as being a victim of the very same apparatus of state control Žižek warns us about. The movies are a dangerous ideological opiate. Proceed with caution. And God save the Queen.

***

Noam Chomsky is suspicious of Žižek. Chomsky has long made it clear he was unconvinced by the postmodern philosophers of the European left, with Žižek being target number one. The legendary linguist and scholar, political commentator, and logician had previously referred to those who subscribe to the ideas of Jacques Lacan and Jacques Derrida as a “cult.” He upped the ante in an interview he gave Veterans Unplugged last December:

“What you’re referring to is what’s called ‘theory.’ And when I said I’m not interested in theory, what I meant is, I’m not interested in posturing–using fancy terms like polysyllables and pretending you have a theory when you have no theory whatsoever. So there’s no theory in any of this stuff, not in the sense of theory that anyone is familiar with in the sciences or any other serious field. Try to find in all of the work you mentioned some principles from which you can deduce conclusions, empirically testable propositions where it all goes beyond the level of something you can explain in five minutes to a 12-year-old. See if you can find that when the fancy words are decoded. I can’t. So I’m not interested in that kind of posturing. Žižek is an extreme example of it. I don’t see anything to what he’s saying. Jacques Lacan I actually knew. I kind of liked him. We had meetings every once in awhile. But quite frankly I thought he was a total charlatan. He was just posturing for the television cameras in the way many Paris intellectuals do. Why this is influential, I haven’t the slightest idea. I don’t see anything there that should be influential.”

Not a man to mince words. That he too is the subject of a feature length cinematic treatment of ideas, one that opens the same month as Zizek’s latest is undoubtedly an irony given the less than warm opinions the two may share of each other and the rarity with which commercially released motion pictures deal with major figures in political, linguistic, or psychoanalytic theory, to say nothing of how unusual it is to have two films side by side that take serious the apparatus of ideas surrounding how films construct and transmit meaning. So the emergence of Michel Gondry’s Is the Man Who is Tall Happy?: An Animated Conversation with Noam Chomsky, which opened November 22 after its local premiere the night before as the closing night selection of the 4th DOC:NYC International Documentary Festival, feels like a unique opportunity of sorts. Gondry’s film is just what it title describes and so much more, but first and foremost, it’s the work of a fellow skeptic. That’s something the Fiennes film never much feels like.

For years Gondry, in the midst of a career nadir revolving around his back-to-back failed experiments in studio moneyraking with The Green Hornet and non-actor neo-realism with The We and the I, would meet with Chomsky from time to time, if only after Chomsky’s secretary and son finally convinced the scholar, who claims not to watch movies, to meet with the French auteur. After filming their discussions, he would retreat to the Brooklyn home he describes as a squat and animate segments which corresponded thematically and rhetorically with Chomsky’s explanations of his earliest memories, the foundation of his moral and linguistic philosophy and the like. After showing Chomsky some of the early results, he continued the process for several more years in fits and starts between projects.

Gondry’s crude, childlike animation is hypnotic, easily digestible and friendly to being juxtaposed with talk. He uses it to varied effects here. Calling film and video inherently manipulative, he lets loose with some of his own brand of film theory at the top. The distance he creates for his audience from the authority of the filmed subject by animating images as opposed to say, Fiennes’s method, is for Gondry the easiest means to invite the viewer to make up their own minds about the information being presented instead of of soaking up the beliefs of the orator like so much cine vodka. He’s always had a Brechtian streak in him.

Upfront, narrating in his thick French-accented English with cursive text appearing over an animation of himself at a table drawing and filming image after image, he deals directly with his intentions to discourse with Chomsky about his life and ideas before he dies, as well as the reason for his method of using animation as opposed simply providing a document of his filmed discussions with the octogenarian. It’s a wonderful self-reflexive device which he returns to throughout the film, as he constantly questions his method and his own competence in the face of such a totemic thinker, intercutting the sequences with snippets of their conversation, which veers from the evolution of scientific thinking to the original concept of Palestine to the importance of early observation of language by children.

Chomsky’s ideas oddly prove an appropriate subject for someone whose work has often been heady in a pop sort of way, but who’s at his best as an irresistibly restless maker of cleverly structured fever dreams. Chomsky’s elucidation of transformational grammar and other aspects of the minimalist program find as oddly fitting a visual analog in Gondry’s aesthetic here, as does the melancholy underneath Chomsky’s unwillingness to discuss his wife’s death. Mortality hangs over the entire project like that; Gondry himself, once an enfant terrible of the music video world, is just turned 50. He openly doubts in the film if he’ll finish it before Chomsky expires.

Doubt is inherent not only in Gondry’s method, but throughout his oeuvre; his films are filled with men who doubt the nature of reality (The Science of Sleep), who doubt their ability to withstand the weight of the past (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind), and who doubt the viability of their profession to sustain the influx of modernity (Be Kind Rewind). He’s candid about his doubts when you talk to him (he once told me at Sundance after too many drinks that he doubted his ability to answer a question about the burden of nostalgia in his films, the young woman in close proximity to him with the forty bottle in her hand might have had more to do with that) and near the very beginning of his conversation with Mr. Chomsky he reveals he’s nervous. Yet to his great credit, he doesn’t flinch and ultimately delivers a film somehow both more sanguine and serious than Fiennes’s admirable but starstruck effort.