In the best documentary films, artifice isn't an obstacle to truth, it's a way in

The great irony of so-called nonfiction cinema is that it is often more willfully deceptive, in its form if not its content, than fiction filmmaking. The skills required to sell the audience on a version of reality in both fiction and nonfiction filmmaking are all ultimately at the service of illusion and deceit, sleight of hand and the flick of a wand. As non-fiction techniques have come to dominate television programming since the late 90s, audiences have become as increasingly used to the time compression and sequence reordering. They’ve grown accustomed to editing cues that inform us of “winner” and “loser” narratives as Colson Whitehead recently put it. Yet by filming often underrepresented subjects in their natural habitats, by reenacting past events that are purported to have happened, the serious documentary filmmaker hasn’t necessarily moved any closer to truth than the reality TV carnival barker. In our second great irony, the documentaries that grasp literal truths and create emotional ones are those that are mindful and conscious of the lies they must tell us to do so.

The fissures between the truth and its aestheticization are a central theme in Dennis Lim and Rachael Rakes’ 55-film, two and a half week programme at Film Society of Lincoln Center, “Art of the Real.” Back for its second year, "Art of the Real" has provided a forum for some of the most enviably startling and thoughtful non-fiction programming the city of New York has seen in sometime. This is not a zone for easy truths; Lim and Rakes have constructed a sequences of films that test the limits of what nonfiction filmmaking can and is meant to do right in front of your eyes. In these documentaries, a form often likened to journalism is clearly an artistic medium.

Art of the Real numero deux opened on the second Friday in April with a shorts block of three movies, each of which ran approximately 30 minutes: João Pedro Rodrigues & João Rui Guerra da Mata's rumination on the remnants of a long defunct Macao fireworks factory (Iec Long), Eduardo Williams’s vérité portrait of bored Vietnamese teenagers who turn to jumping between the windows and roofs of buildings for amusement (I Forgot), and Matt Porterfield’s unscripted narrative (Take What You Can Carry), about a young American woman in Berlin we find, according the the festival’s programme notes, “attempting to reconcile her need for a stable sense of self-identity with the fulfillment she derives from her itinerant lifestyle”.

In no other place can I think of would a curator deliberately choose to show these works together. One has the shape and look of fiction, one pays strict adherence to vérité documentary and another blends archival photos and footage, reconstructions centered on figurines, oral history, and glimpses of contemporary life in the fireworks trade (the sound of fireworks is around every hypnotic nook and cranny of Iec Long). Together they pose as representative of various strands of contemporary non-fiction. "Art of the Real" is full of such uncluttered pronouncements and provocations, many of which are short in form —for Lim, Rakes and the high brow audiences they court, the feature has no special closeness to the truth.

The centerpiece of the festival is a partial retrospective of the great genre-bending trailblazer Agnes Varda, whose remarkable work in documentary essay (The Gleaners and I) and naturalist fiction complicated by self-conscious documentary framing (Vagabond) butts up against a series of works that fall all over the surrounding spectrum (Black Panthers, Mur Murs, Daguerrotypes).

Perhaps even more revelatory than revisiting Varda’s essential oeuvre is Lim and Rakes’ sidebar “Repeat as Necessary: The Art of Reenactment” a strand that interrogates the various ways doc filmmakers have used seemingly narrative reenactments across a broad spectrum of documentary phenotypes. Reenactments have their detractors; in the wake of the Jinx craze, Richard Brody attacked reenactments en masse just three weeks ago in the New Yorker, claiming they “never work.” But he back-tracked a bit the following week when it came to the work of Elisabeth Subrin.

The Temple University professor and stalwart experimentalist’s program unfurled on Saturday afternoon. It led off with Shulie, a “recreation” of a 1967 documentary about the then-22-year-old Art Institute of Chicago student Shulemith Firestone. Shulie is a canonized classic of the post-New American Cinema era avant-garde film, but little known outside the hard cinephile circles. Three years after the original documentary was made Firestone, born Shulamith Bath Shmuel Ben Ari Feuerstein to Orthodox parents in Canada before spending her childhood in the American midwest, would pen The Dialectic of Sex, a foundational text of Second Wave Feminism and become one of the most revered, and misunderstood, of feminist writers.

Shulie screened in front of Lost Tribes and Promised Lands, a meditation on memory, national purpose, and gentrification in Subrin’s Williamburg neighborhood that powerfully juxtaposes flag-strewn edifices in the month following 9/11 side by side with their more contemporary, often gentrified incarnations. Sweet Ruin, which offers up Gaby Hoffman in gender-bending dual roles, playing shards of the characters Maria Schneider and Jack Nicholson were supposed to play in the never filmed Antonioni screenplay Technically Sweet, closed the troika.

The subject of Shulie, who died at 67 in 2012, is played by Kim Soss. She resembles Firestone superficially and recites, line for line, dialogue that is taken from the unreleased film made about Firestone by Chicago’s stalwart leftist documentarian outfit Kartempquin. The rough hewn, period-appropriate 16mm portrait of this young woman proves to be a potent meditation on the aesthetics and desires of the late ‘60s. Shulie is interviewed on camera, shown getting a bullshit critique from several male instructors, intermittently explores nature, and talks about bonding with professional negroes whose highest possible aspiration was a job at the post office. What the accumulation of these moments provides is nothing less than a glimpse into the flowering of a feminist sensibility as it intermingled with anti-war sentiment and Civil Rights agitation. The nature of reality’s spell in Subrin’s hands is pitched at an angle where we can glimpse the artifice (during one anti-Vietnam rally in the film, the viewer can see modern cars, and a young black child in a black, mid-’90s, Michael Jordan jersey) just enough to meditate on its construction, to redouble our efforts to see Shulie’s message in our own time.

***

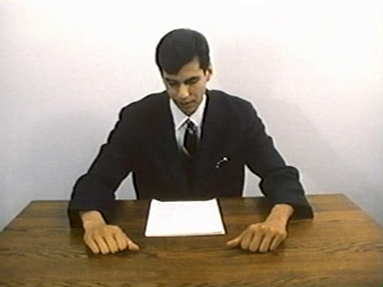

Earlier that Saturday afternoon, Jill Godmilow’s What Farouki Taught and Harun Farouki’s Inextinguishable Fire began the sidebar. Godmilow’s film, made while she taught at the University of Notre Dame in the mid ‘90s, celebrates Farouki’s earlier German black-and-white film with a shot-for-shot English-language color remake and an epistemological investigation of its methods. Godmilow’s film opens opens with Walter Benjamin’s discussion of art in the age of mechanical reproduction, before advancing to a harrowingly personal statement by a Vietnamese man (clearly a caucasian, speaking English in Godmilow’s version), sitting at a desk in jacket and tie. He stares into the lens and relays a story of being victimized by American napalm bombing, after which he was unconscious for 13 days. Then he pauses and says something so startlingly painful and true about how Americans always see, or rather refuse to see, the collateral damage caused by our empire, that the food I was chewing fell right out of my gaping mouth:

How can we show you napalm in action? And how can we show you the injuries caused by napalm? If we show you pictures of napalm burns, you’ll close your eyes. First you’ll close your eyes to the pictures. Then you’ll close your eyes to the memory. Then you’ll close your eyes to the facts. Then you’ll close your eyes to the entire context. If we show you a person with napalm burns, we will hurt your feelings. If we hurt your feelings, you’ll feel like we tried napalm out on you, at your expense. We can only give you a hint of an idea of how napalm works.

In both films, the man delivering the monologue takes a lit cigarette from an off-screen ashtray as the camera pushes in and tilts down, stubbing the tip out on his wrist as a voiceover tells us that, while cigarettes burn at 400 degrees celsius, napalm burns at 3000 degrees celsius.

This man is an actor, and Godmilow’s film is agit-prop of the highest order. We don’t know whether this particular napalm incident happened or not, even if Seymour Hersh’s recent piece makes it startlingly clear how common such brutality was. It’s the spirit of the thing that counts; we know it to be emotionally true. Such things did happen, and we as American typically refuse to care. The rest of the film, which blends reenactments and news footage, direct address, and voice-over, indicts the American capitalist engine and the Dow chemical company of Midland, Michigan specifically for manufacturing these tools of destruction when they could use our advanced manufacturing and biochemical capabilities to make products for the world’s betterment.

Godmilow’s film runs about eight minutes longer than Farouki’s; she is interviewed at film’s end, on her own film’s set, about her feelings toward Farouki’s film, which was never shown in the United States during the war. She declines to call it a documentary per se, saying “We don’t have a name for this kind of film. We should get one I think. It’s inexpensive, it’s direct, it’s strong, and for me it replaces the documentary’s pornography of the real.” Another, offscreen voice replaces Godmilow’s, continuing, “pornography of the real, as in the way we get off on war footage, where there’s blood and dead bodies flown all over the place. We love to look at the suffering and shame of famine victims, AIDS patients and unemployed workers. We’re seduced by the realness of the horror. Turned on in a kind of sexual way.”

Affecting, politically conscious remakes unearthed in an era full of mindless, commercial ones, Shulie and What Farouki Taught take the unlearned political lessons of yesterday buried within barely seen films and use them to haunt our present. Perhaps one day we’ll get better at heeding their wisdom and stare their truths in the face.