The Palo Alto Borders was my psychogeographical center. It seems strange to say that of a store, never mind an outlet of a giant and mostly uniform chain, but there was nowhere else I was so free to grow up. Borders became for us the mythic “third place,” not school or home, where young people could encounter each other on accident.

If you drive West on University Avenue in Palo Alto, California past the downtown area, you will pass under the train tracks, over El Camino, and onto picturesque Palm Drive and the grassy expanse of Stanford University.

If you go East, you drive first through North Palo Alto and its multimillion-dollar suburban compounds, then over Route 101 and into East Palo Alto. Developers have used this area in tax-starved EPA to store big chains that can’t afford the space in Palo Alto. The Home Depot and the day laborers waiting outside stay on the other side of the bridge, but if you walk up University heading East, before exiting Porsche and Ferrari territory, you can see the hulking blue Ikea rising across eight lanes of traffic.

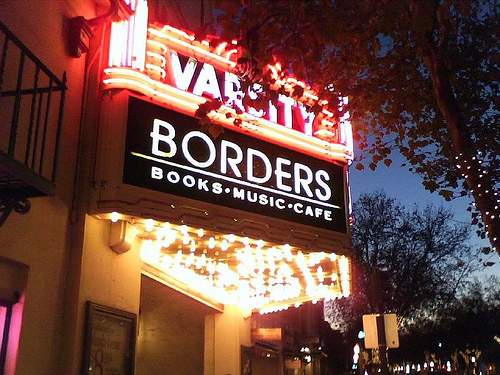

The Borders Books on University Avenue at the geographic middle of this whole mess, has been housed in the former Varsity Theatre since at least 1996, when I first saw it. I never knew the Varsity, but its neon sign is still there, white and pink and red above the bookstore’s own, as is the theatre’s original ceiling and its intricate moldings. Today, the signs look archaeological. Borders is joining The Varsity in the past.

The commercial development of downtown Palo Alto is not a classic case of gentrification. I’ve seen relatively few wealthy chains pushing out local institutions (though it happens); instead, the inherent turmoil of capitalism drives one gourmet frozen yogurt shop to replace the previous tenant, another gourmet frozen yogurt shop, to join the other gourmet yogurt shop on the block. There’s an Italian cafe, a Venezuelan cafe, a Croatian cafe, a Starbucks, and a Peet’s Coffee for good measure. If you stop in at any of these places, you can hear middle-aged tech folks talking about venture-capital funding in five or six different languages. Never has cosmopolitanism been so dull.

Palo Alto likes to think of itself as a national intellectual hub: You can find all the yogurt and coffee you want. But good luck looking for something to read.

The charmingly indie new/used Megabooks that used to live next door to Borders became either a Korean barbecue place or a clothing boutique—I can’t remember—and another bookstore downtown devoted to Stanford students closed and was reborn as a mattress store. With the death of Borders, Bell’s Books—a precious and forbidding collectibles shop with an imposing iron grate—will be the last bookstore standing in the downtown area.

As a kid, I saw Printers Inc. Bookstore and Cafe on California Avenue a couple of miles away from downtown turn into Printers Inc. Cafe and Stationary Shop. With the closing of Know Knew Books across the street, there will be two other bookstores left in Palo Alto proper—a small Books Inc. in the ritzy Town and Country shopping center, and the Stanford campus bookstore. Ebooks alone cannot justify this paucity.

Growing up, the Palo Alto Borders was my psychogeographical center. It seems strange to say that of a store, never mind an outlet of a giant and mostly uniform chain, but there was nowhere else I was so free to grow up. For me and my friends, Borders became the mythic “third place,” not school or home, where young people could encounter each other on accident. TV shows conjure these unrealistic hangouts for a reason, whether it’s the Bronze in Buffy or the Peach Pit in 90210. They are spaces of collision and reaction, somewhere to find others and be found.

When I was 12 and my friends and I first started to explore the world, we didn’t have anywhere to go but downtown. We would walk to nowhere in particular or take the 35 bus, just to go alone together to the places people went. It didn’t hurt that at the time, there was a comics store (Heroes), a candy store (How Sweet It Is), a great pizza shop (Pizza A-Go-Go), and CD store in addition to Borders. Throw in Z Gallery, a tacky furniture and “art” chain whose couches became temporary living rooms until we were shooed away, and a few cheap and short-lived restaurants, and that was my downtown—a small circuit of limited shopping opportunities.

I must have walked hundreds of miles between these places growing up. But by the start of high school, all except Borders had closed.

Why didn’t we go to a library? Or a park? Because public spaces were custodial. Librarians looked like teachers, and we didn’t want to be shushed. In Palo Alto on the weekends, the parks are marked off for Little League or AYSO or youth lacrosse games during the day. We were trying to avoid the PTA mafia, not waltz into their lair. And just try hanging out in parks at night without risking a chat with the police.

Borders, on the other hand, didn’t have any list of unacceptable behaviors. Getting kicked out was rare, and the pierced, tattooed employees looked nothing like our parents and were generally unworried by our behavior. The bookstore had the single most accessible restroom and water fountain in the entire downtown area, so the phrase “I need to go to Borders” became a comprehensible alternative to “I need to go to the bathroom.” The workers there closed the bathroom before the rest of the store, leaving Palo Alto teens without a single toilet that isn’t tucked behind a paywall.

Mostly when we went to Borders we would pick an uninhabited aisle (Christian Lit was probably the most popular), sit down, and read aloud from the most outlandish book we could find. Or we’d go from CD-listening station to station, trading headphones, discovering not just bands but popular music itself. We would spend hours, walk out without buying anything, and come back the next day to do the same thing. In return for their hospitality, I bought every birthday and holiday present for a decade at Borders.

On Friday afternoons in middle school, groups (by then co-ed) that could easily hit double digits would wander the blocks lazily, not having yet discovered the booze, drugs, and sex that would later send us to smoky basements in houses temporarily without parents. Borders was the assumed launching place for any downtown meetup; we learned each other’s waiting aisles. On nights we felt enterprising, we’d gather a group for capture the flag and use Borders’ two levels as opposing territories.

As a romantic destination, Borders lacks a certain ambiance, but it was the scene of countless half-dates and more awkward proto-flirting than the dances at the private girls’ school. The human sexuality aisle was our real sex-ed class, a copy of Sextrology —probably unsellable from all the adolescent finger smudges—taught us the various ways bodies fit together and why the punch lines of certain jokes heard years ago on playgrounds made sense. We read each other’s sexual horoscopes loudly, and usually failed to stifle giggles when an actual customer walked by.

As half-dates became the real thing, Borders was still the place I felt most at home, surrounded by plenty of books I could jabber about nervously. I still remember making out in one of the fiction aisles with my high-school girlfriend. It felt adult at the time.

Recently, I was in line at one of downtown’s many coffee shops—the Italian one, which has gone through three different names, as if incessant re-branding could ward off the artisan shaved-ice stores nipping at its heels—when I ran into a young woman I thought I knew but could not for the life of me place. We stood for a few seconds in liminal, mutual semi-recognition until she said, “You used to hang out in Borders a lot, right?” She was a longtime employee. After a long pause, she turned to me again and said, “You think we don’t see you. But we do.” She was right, it never occurred to me that anyone was really watching. Those employees probably knew more about my personal life from peering out from behind the counter than any of my adult authority figures did. It was all there on display, a relatively small stage for acting out adolescence.

Since I only see it on the occasional visit, I now experience Palo Alto’s change in jumps and bursts. In the week Jonathan Franzen released Freedom, Borders had a series of circular piles stacked four feet high. When I went back most recently, it had already begun its commercial death march.

The tables were stacked with the remaining books, but also perfumes and bathroom accessories, the disassembled shelves and giant multi-disk CD players unearthed from their listening stations. You could measure the closing countdown in days or percentage points. First 20-40 percent off, then 40-60. Finally, it hit 70-90, with nowhere left to go. As the days passed, the number of customers dropped, but their individual shopping baskets got larger in direct proportion to the bleeding discounts.

While browsing what was left of the social-sciences books on the underused left side of the second floor, I heard a group of three young teenage girls sitting in a circle in the Christian Lit aisle having a familiar conversation around a book that couldn’t sell even at 80 percent off, not if someone was holding it.

“Virgos express themselves with bold colors like green.”

Editor’s Note: An earlier draft placed Books Inc. in its former location in the Stanford Shopping Center. It is now in Town and Country Village, but the author is reliably informed that it’s still a pretty shitty place to hang out or buy books.