A Roundtable on Marie NDiaye's Ladivine

Marie NDiaye is not a household name in the English-speaking world. Not many Francophone writers are, of course, but especially not writers like the elusive, mischievous, and downright forbidding author of the just-translated Ladivine. Her “opaque lyricism,” as Amy Gentry put it for the Chicago Tribune, “doesn't always lend itself to easy translation,” and while Amy is right to observe that she makes the nouveau roman new again, such a novel form of novel is not necessarily an easy sell. NDiaye's cold prose is also, to put it bluntly, sometimes an unpleasant experience, and while refusing full access to her characters might perfectly fit the “disjointed ethos of contemporary Francophone literature”—as Jeffrey Zuckerman observed at the New Republic—reading her work can be a taxing experience, by turns, bracing and unpleasant… until she staggers you with the scorching familiarity of the terrible world we live in. You can call her ir-realism Kafkaesque or magical realism, if you want—many people do—but it also turns out to be so banal, so viciously normal, that—as I put it in my own review at Okayafrica—“her metamorphoses are not shocking transformations; they are the sort of thing that happens, when daily life makes you into a thing.”

Amy Gentry, Jeffrey Zuckerman, and I spent an afternoon chatting about this novel, which we all liked a lot, and which confused us all, in different ways, a lot. -AB

Aaron: So, first of all: Ndiaye’s novels have transformations in them. There are birds in Trois Femmes Puissantes, a guy gets changed into a snail in La Sorcière, and in La Femme changée en bûche--if I can be trusted to translate-- “The Lady Changes into a Log.” This is probably why critics like to call her “Kafkaesque.” But does marking her transformations as a stylistic feature--and putting that Big Name of Literature on her, plus and -esque--have the effect of flattening out what's most interesting about her work?

Jeffrey: NDiaye does use transformation as a stylistic trick, though by an odd quirk, it’s only shown up in two of the books translated into English. In the review, I said this was an allusion to Ovid, among many other writers and the general tradition of folk tales. But I also think NDiaye’s trying to do something different. She’s letting a lot of ambiguity remain--as

I think her real innovation is pushing that concept as far as it will go. The dogs become protectors. The birds in the entr’actes of Three Strong Women achieve the escape the protagonists prayed for. The transformations are a jump into another realm, a suspension of the normal rules of engagement for daily life, and that’s her real achievement--an ability to play with the tropes and rules of realism, and then break with them in a way that feels relevant and not merely escapist.

Aaron: That might be a segue to something Amy said on Twitter, calling the novel "a study of spaces where identity stutters and goes silent.” I love that formulation, because the novel is so much less about who we "really" are than about the kinds of spaces in which who we really are changes. So there’s nothing to escape to, or from.

Amy: Thanks Aaron! I think that was me reacting directly to the headline attached to my review--“a rewarding study in identity” didn’t feel right at all, but it spurred me to think about what did, and to formulate it on Twitter better, maybe, than I did in the review itself. All passing novels are, as you put it on Twitter, “weird.” But Ladivine, more than most, struck me as being about the very act of vanishing or melting that is implied in the word “assimilation.” The blankness and repetition and doubling, and even the animal transformation--which I hadn’t thought of as Kafkaesque, but I think it would be interesting to read through Deleuze’s reading of Kafka (wow I grossed myself out typing that)--all seem to me to speak to the trauma of erasure in a way that most passing novels I’ve read don’t, with the exception maybe of Nella Larsen’s Quicksand.

Aaron: In “The Metamorphosis,” turning into a vermin is kind of comic, but the humor of it is really… absent in NDiaye, isn’t it?

Jeffrey: Yes, NDiaye’s horribly serious. It’s almost disappointingly necessary, I guess. There’s a very long chapter in the middle of Ladivine that I genuinely wondered if it might be a dream sequence. And if there was any humor anywhere in that long chapter, that would have wrecked the effect that she was trying to achieve--that the characters were in some kind of purgatory where their past could not be escaped. I guess it’s hard to be funny if you want to become a saint?

Amy: Well, I thought the middle section of Ladivine was funny. Funny and creepy.

Aaron: Which parts? When they go to wherever-it-is-they-go, the place that might be Africa?

Amy: Yeah, the vacation part. Ladivine the Second’s section. Maybe I just like the absurd. That is definitely my favorite section.

Aaron: The absurdity of all the wedding stuff, the clothes, the hapless husband… it has elements of comedy; misrecognition, awkwardness, out-of-placeness. But absurd becomes uncanny when the misrecognitions come true.

Jeffrey: In most comedies, silly things recede into the background. But everything just kept coming back, and getting worse.

Aaron: Also the “bitter bread” line: "Had she not made of the servant's life a bitter bread?" At first it's just this vaguely biblical-sounding quote, but with repetition it becomes an incantation.

Amy: Here’s where I admit that not only is this the first NDiaye I’ve read, but it’s the sole complete work I’ve read--I looked at excerpts of Three Strong Women for my review, but Ladivine was my intro to NDiaye and remains my only real point of reference.

Second confession: I loathed the first 100 pages and succeeded in powering through only with a numbing glass of sauvignon blanc by my side. I was viscerally angry with it. I spent a summer in grad school reading Gertrude Stein’s The Making of Americans and that was a complicated summer for many reasons, but as I was reading the Clarisse-Riviere-did-this-and-that section I just kept thinking, “Someone already did this a hundred years ago in a fabulously failed experiment in narrative unfolding, and although it was interesting in 1910, there is just no reason to repeat this experiment in 2016.” Stuttering and logorrhea are not only defining characteristics of Stein, they are central to her idea of how identity works--through endlessly iterated repetitions and differences--and that, to me, is still the only real way I can make sense of the style of the Clarisse Riviere section. So it’s weird that the Stein comparison didn’t make it into my review.

Jeffrey: It’s so funny that the first part of Ladivine bored you. I was similarly bored and miserable in a couple of parts of Three Strong Women, which was the first proper NDiaye I ever read. But after reading a couple of reviews, I realized that I’d skipped over a couple of crucial details that completely altered the story. And I started noticing the same sort of crucial-detail-cloaked-in-incantatory-prose trick in Ladivine, with the result that I was enthralled throughout that entire first section. The result of learning how to read NDiaye? I think that’s the challenge--that you have to absolutely engage with each sentence before you can really get a grasp on what she’s trying to pull off in her novels.

Aaron: She reveals more and more the deeper you go; if you just read on--if you expect things to get explained later, rather than dwelling with the moment--you miss so many crucial things, things that are crucial for the way they don’t make sense, and won’t.

Jeffrey: So you’re sort of trying to figure out when something goes off the rails and whether or not it’s supposed to. Somebody dies early in the book, and it’s metamorphosed into “entering the forest.” I actually read the second death without realizing it at first. I just saw there was a forest again, came to the end of the chapter, and had to tell myself: “Wait, somebody just died… I need to go back and figure out where and how it happened.” I actually read that damn section three or four times before I could put everything together.

I almost want to say Stein is easier to deal with just because you can miss something and it’s not the end of the world.

Aaron: My confession is that I’ve never read The Making of Americans. But, Amy, you are giving me ammunition for my inarticulate feeling that calling her “Kafkaesque” is, at best, an obvious analogy, and not at all the best one. Maybe if I had read more Stein, I’d be able to say so from a less cranky place.

Amy: In no world will reading Stein make anyone less cranky! But I take your meaning, and certainly the structure of the novel, and the structure and title of Three Strong Women, feels like a direct evocation of early Stein, Three Lives in particular. Given the complicated racial stuff in Stein’s Three Lives, it would have been easy to write a much longer piece about the relationship between NDiaye and Stein than I had space or time for (Melinka/Melanctha alone kind of begs for the comparison). Stein is how I made sense of NDiaye while I was reading Ladivine, but afterward when I discovered her Nouveau Roman lineage it was so much more direct that I felt a palpable sense of relief. Maybe since I know less about the Nouveau Roman than about Stein, it felt safer, less like a rabbit-hole I could fall down. That’s a reviewer regret surfacing.

Jeffrey: NDiaye was originally published in France by the publishing house that became famous for bringing out all these Nouveau-Roman authors. And that framework does help clarify what she’s trying to do, though at moments, the language grows more powerful than the story being told. But it would be nice to have more time to think about these sorts of things, more time than a review allows.

Aaron: This is why I wanted to do this conversation, actually. “Reviewer regret” is as much a part of writing a review as being saddled with an impossibly simplistic headline. It’s always what happens. But with a novel like this one, it feels like even more of a problem; the simplifications are somehow more crucial? (This is why I was being all cranky on twitter, btw; every single review of NDiaye’s work that I read makes me say “This is smart! BUT OMG NONE OF IT IS ENOUGH).

Jeffrey: There is always SO MUCH that doesn’t get discussed at all!!

Amy: Yeah--so many times the review feels like the thing you have to get out of the way to start thinking about the book for real. It does valuable thinking work in a way that can only be done on a deadline but unfortunately it’s more process than product many times.

Aaron: Which is strange because reviewing is so often oriented towards appraisal, towards making some kind of final judgment on the book. But, I mean, c’mon, how can we know if a book is any good (or bad) if we haven’t had time to sit with it, talk about it, ruminate? Writing on deadline like that--like you have to, because it’s pegged to release dates--tends to produce such a false sense of certainty.

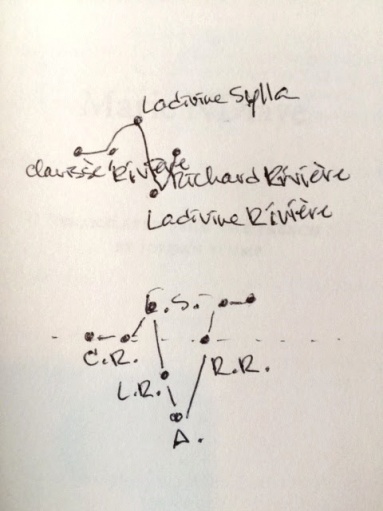

Jeffrey: I actually handed in my review late. I mean, my editor at TNR was a saint and gave me amazing edits and didn’t complain, but he had one day to deal with my entire piece. I read the book on two plane flights, filled up five notebook pages with thoughts and notes and drawings. That’s actually why I mentioned an EKG in my review--I sketched a diagram here with dots for each chapter that basically went up and down the generations like an EKG:

Aaron: WOH.

Jeffrey: Yeah, it’s one of those things that just totally clicks once you sketch it out. Like that time Nabokov drew a map of the Samsa household for his lecture on The Metamorphoses. Anyway, the result was that when I sat down to write the review, there were about 20 different topics or themes I could have focused on. And I think I was only able to hit about five or six of them in my review, so when I look at the finished piece, I feel quite a bit of regret for everything I didn’t discuss enough, or didn’t discuss at all. Silence is actually a really big factor in the novel--and it’s only here in this discussion that I’m hearing anyone really allude to that.

Would I have had time to work that into the review if I’d had more time, instead of worrying about whether or not I needed to talk about magical realism and whether or not NDiaye was actually building off of that? Maybe. And maybe it’s good to have an editor say, “Stop. We’ll clean up the prose, and pull together your thoughts so far, but right now we need to tell readers whether or not this is a book they need to grapple with”?

I definitely thought this was a book I needed many more people to fall in love with. I was okay with not cramming every one of my thoughts into the review because I wanted to get readers started reading NDiaye. And eventually I might get to find out what in NDiaye’s writing would make the book spark fireworks in their minds.

Aaron: When did you start to like the novel, Amy?

Amy: The section that sold me on the book, and on NDiaye in general, was the second section, what happens with Ladivine the Second and her family in the unnamed country--the total dissolution of her identity in a kind of ecstatic surrender. Because ultimately while I respect the Steinian experiments, I don’t think they’re enough in 2016. Anyone can replicate Stein (sometimes totally by accident, after reading The Making of Americans for an entire summer, very embarrassing). The uncanny stuff that happens in the unnamed country was spine-chilling and brilliant to me. First of all, it was filmic in a way that reminded me of the Thai director Apichatpong Weerasethakul. (Pretty sure I deleted that comparison from the review, too. Enjoy these deep cuts from my notes, guys.)

Aaron: Oh, I am! For example, Apichatpong Weerasethakul? I don’t know his work at all.

Amy: I’ve only seen Uncle Boonmee Who Can’t Recall His Past Lives, which won the Palme D’Or at Cannes in 2010, so I’m being highly sketchy in referencing it. And I don’t feel particularly qualified to talk about it, except to say that it’s beautiful, boring, eerie, static, uncanny, vivid . . . dreamlike . . . that’s it, that’s all I can say about it. Half the time you have no idea what’s real or not. And it puts you in a trance state watching it. The scene in Ladivine that was most evocative of it was the one where Ladivine’s family is eating dinner with the tour guide’s family under fluorescent lights. Everything seems to be hanging in the air somehow, flattened out.

Jeffrey: In the middle chapter? Yes, I kept expecting everything to snap back into a sort of reality. Life in Bordeaux is real. Life in Berlin is real. But that vacation seemed like the weirdest experience ever. It didn’t help that all sorts of unreal things were happening--the lost (and never-packed) clothes reappearing for sale on the streets, the people insisting they recognized Ladivine Rivière, that whole murder-that-wasn’t-really-a-murder. Everything just seemed to be on pause. Like a trance state, yes.

Aaron: For parts of the novel, it feels like it’s almost a shame to keep reading… like, you could just spend the whole morning just humming a few sentences and get something out of it. I re-read passages from it SO MANY TIMES. At first, out of total WTF confusion, and a sense that I was missing something (or trying to figure out some detail), and then, at a certain point, it felt okay, like that was supposed to be how you read it.

Amy: Yeah. It took me a minute to figure out she’d been killed. I was like, wait, murder happened, wake up Amy.

Jeffrey: Are we talking about the first death? That was like a Hitchcock movie. I could practically hear the music as Freddy walked out of the frame. But the second death was what tripped me up. I didn’t figure it out until I came to the second forest scene.

Aaron: Freddy was such bad news. The book is also filled with these sudden, brutal events, but also, when I was describing the book to someone, I called it “like wading through cold honey.” You can’t move fast, even if you want to.

Amy: Cold honey is a good comparison, especially in the Clarisse Riviere section. I found the second section to be much different stylistically, more image-dependent (filmic) in a way that was easier to move through. And then I love how masculine violence explicitly becomes an issue in the second section. Clarisse Riviere’s death notwithstanding, I absolutely was not expecting that. I was totally prepared for this to be a book in which race and identity are these floating signifiers, and gender is only important insofar as femininity is a hyper-legible surface (as when Clarisse Riviere stares at herself in the mirror). I was prepared for her murder to be this nihilistic act of random fate. And then comes Ladivine Rivière’s nightmare vacation with her family of Bergers, where her husband (until then described as very feminine) “mans up” to protect the family, and instead of making her hot for him (as in countless examples I can think of, from Hemingway forward), it frightens and alienates her.

Aaron: And so ineffectual! If his idea is to use violence to create safety for his family, it’s also scary because it does almost the opposite. Killing Wellington doesn’t kill him, it just makes his presence-as-violated a new source of terror. There’s no escape! To go back to Jeffrey’s point, earlier. Violence creates a new reality, one marked by that violence.

Amy: Can I digress quickly into a dumb aside?

Jeffrey: Oh, definitely!

Aaron: Please do.

Amy: There’s this genre of films my husband and I jokingly call “Lonely Shoe” movies. In these movies, the paradigmatic moment is when a “modern” man thrown into a threatening situation acts like a coward, and fails to protect his wife and/or family. Nobody gets hurt, but the whole rest of the movie is about the couple dealing with that moment. (“Lonely Shoe” comes from one particularly egregious example where they find a single shoe afterward in a sad ruined shack, like “ooooh god without masculinity this relationship is as useless as a single shoooooe”.) There are really good comical films about this too, including Force Majeure by Ruben Ostlund. The dumbest examples are often set among westerners traveling in impoverished countries, for obvious reasons (and also following Hemingway). Now I see Lonely Shoe moments everywhere. When the Lonely Shoe moment in NDiaye came, I suddenly realized how hungry I was to see it play out a different way. Like, Marko PASSES the Lonely Shoe test. And it’s horrible, horrible, horrible. Just as it would be in real life. The fantasy about heterosexual relationships getting somehow revitalized by an infusion of primal violence from a “primitive” place is just squashed.

Ladivine immediately recognizes his action’s relationship to colonial violence, and to her own mother’s death, and perhaps even to some repressed memory of racial erasure in the maternal line. After all, Ladivine is already herself the “return of the repressed,” she’s named after her erased grandmother. When the children “turn” (that dance the little girl does on the bloody pavement!), I get chills. It’s like something out of Henry James, the idea of children as these empty innocent vessels who pick up on subtle corruptions and become monsters. There’s this very clear way of asserting individuated identity in the novel that has to do with patriarchy and colonization (and CARS), and when the children get initiated into it, Ladivine is like “That’s it, dog time.” The dog is this haunting trace of racial memory, and stands for the refusal to participate in any identity formation that relies on erasing an “other.” So for me, when Ladivine is all “fuck it, I’d rather be a dog than like you guys” that’s the novel coming down against identity, at least as it’s formulated in the West, the way Clarisse Riviere formed hers.

Aaron: Now, I’m thinking about the way Ladivine’s choice replicates her mother’s death, but, by literalizing it, really blows up the terms of the metaphor. The “death as being lost in a dark forest” conceit is pretty played out; I immediately thought of Dante, but there are half a dozen other places you could turn to for thinking of it as a literary reference, since it’s basically just a city-person’s way of marking the edge of The Known World, the point after which there be dragons, etc. But then Ladivine literally gets lost in a dark forest! She’s like “The known world sucks! Peace!”

Jeffrey: You know, that was something I was really debating about as I collected my thoughts for the review. I think I suggested that a “happy ending” for many of the protagonists would be the inverse of a Cinderella story, where the fancy (false!!!) dresses were stripped away and we saw the real person underneath. Colonialism really does explain how this drama does play out to an appropriate end. But I suppose I’ve resisted it because NDiaye doesn’t really feel a strong kinship to Senegal. Her father’s homeland is visible in her last name (she didn’t change her name to her husband’s), it’s visible in her appearance, but she is definitely and without a question French. So trying to tie these transformations to African folktales, and draw on anti-colonialist sentiments widespread across Africa seems to be reading too much into an identity that NDiaye doesn’t believe she possesses.

Aaron: Well, I’ve actually been surprised by how much Africa is in this and some of her other books. There’s an interview where she is very clear about some of the ways she isn’t African:

“The only thing that changes when you have an African origin is that you are black, it’s visible. But that's all. I was raised by my mother alone, with my brother, in France. Not by my father, who I never lived with, and I did not go to see Africa until the age of 22. I was raised in a 100% French universe. In my life, the African origin does not really make sense -- if we know, it’s because of my name and the color of my skin.”

And she has been clear that she is French, in a very basic Don’t-Other-Me kind of way, though that claim is made in very specific opposition to a nativist story about France. So she doesn’t believe in at least some kinds of sentimental diaspora; I think I read an interview where she said that she went to Africa and found “nothing she recognized.” So, she didn’t feel a primal connection, the Roots narrative we get from Alex Haley or whatever. But both of those claims feel very oriented towards the argument she’s having with other people; in those argumentative contexts, she is French, and she isn’t African. But also, she did go to Senegal!

Amy: Can we start talking about racial identity as a thing that’s very different in America than it is in France? I think this is something that gets lost in translation.

Jeffrey: YES! This was one of my favorite things to think about when I was in Paris for work last fall. I met a friend at a bar called Le Comptoir Général and apparently it is very hip and stylish--my friend was telling me that he’d seen Solange Knowles there--but I just felt totally at home there. What’s special about the bar is that it’s an entire place (not just a bar, it also has a couple of small stores and a restaurant and a mock schoolroom) devoted to Francophone Africa. It’s roomy, it’s beautiful, and it’s very unmistakably African. If that bar was picked up and set down here in New York City, it would either become ghettoized, or it would become a caricature of itself--a museum, rather than a bar that also feels like a warm, welcoming window into Africa. I saw people of many different ethnicities there, and it was a similar makeup to what I saw on the streets everywhere. I get the sentiment that blackness is a much smaller marker of identity in France than in the USA--but it is not invisible. And I suppose I should emphasize that Paris is very consciously urbane. It has to be, since tourism is such a large part of its economy (Paris is AirBNB’s largest market), and if you look at the other cities where Clarisse lives--Bordeaux especially--that’s further south, and certainly a bit less densely populated and less markedly cosmopolitan. Bordeaux would still have plenty of immigrants from Francophone Africa, but it would be easy to understand why Clarisse might want to pass as white or authentically Gallic in a less diverse environment.

Amy: I think the whole identity question is kind of a red herring. It’s pretty clear to me that unstitching these types of distinctions is a crucial part of what Ladivine is trying to do.

Aaron: Can we put “red herring” alongside of “brown dogs” and “green women”? I feel she provokes some of these connections; in Self-Portrait in Green, e.g., she does some interesting things with the “I, Marie NDiaye, am writing this” framework.

Jeffrey: Yes, that’s part of the reason Self-Portrait in Green is my favorite of the NDiaye novels I’ve read so far. It’s also much easier to access as a reader, since it’s in the first person and you can’t really find yourself at odds with multiple narrative frames. But yes, there are lots of ties between NDiaye’s life and what’s presented in her books. I almost wonder at times if she’s writing her books as psychoanalytic exercises wherein she struggles with various questions and issues that do bear upon her own life (national and racial identity certainly among those). So then we end up seeing a sequence of metamorphoses: NDiaye > Book’s characters > animals the characters are transformed into...

Amy: Well using and messing with the authorial “I” is straight out of the Nouveau Roman playbook. ;) And the lineage there--yes, racial identity and national identity are very very important. I just think we’re reading it through an American lens that doesn’t necessarily do justice to the nuances she’s gesturing toward. I think this is where her resistance to being called a “black author” in the American press is seated; and the characters in Ladivine too are constantly oscillating between erasing and reasserting their origins.

Aaron: Right, everything depends on what the phrase “Black author” is being used to mean and imply. Her resistance to those terms--especially in publishing talk, and the categories formed by critics--is crucial. But that’s also where it feels like her move to Berlin was, itself, a kind of semantic act. Not that she’s any less French as a result of it, but that her Frenchness was always already contingent or mediated by racism, which Sarkozy comes to really embody for her. But it isn’t new: in the preface to her 1991 novel, En famille, she asked “from what country am I? Aren’t all countries for me a foreign country?” She goes on:

“Since my childhood...a state of constant malaise, or rather a perpetual sensation of displacement. It seemed to me that I never felt at home anywhere and there was nowhere one would consider me a compatriot.”

Amy: Yes -- I would say all identity is implicated though, not just Frenchness. Maybe not even just whiteness.

Jeffrey: All these characters exist in unease. They’ve missed that crucial imprinting they were supposed to receive if we’re thinking about identity the same way Judith Butler discusses gender. And then they don’t know what to do, so they keep trying to make their lives work one way or another.

Aaron: Do you think I’m trying to push her into a place where she is trying not to go? I guess I do want to read those statements in terms of race, but maybe that’s an unsubtle way to read what she’s doing; maybe it’s not about race, except insofar as it’s one of many forms of alienation? Specific, but no more so than all the other specific forms?

Amy: On the contrary I think it is very much about race--but in a very different way than I think we are used to thinking about it in America.

Aaron: I wouldn’t disagree with that, at all. Maybe we could go back to the dog, and what it’s supposed to signify; using abstractions like “race” take us away from the embodiment she uses to talk about these things. And so, what does it mean that she embodies [whatever it is] as a dog?

Jeffrey: "that this embodiment is canine in form"?

Aaron: Right. What are the semantics of that formalism? My first thought was that we’re seeing The Violence Inherent in The System: she turns into a dog because, having been violently killed, she now sticks around as a Sign of Violence. But the dog is so… basically benevolent, isn’t it? It’s just hanging out, watching. We have that early scene where a dog suddenly killed someone (was it Marko’s father?) and the mother has opinions about how dogs are bad. But that’s not really it.

Amy: But the dog didn’t necessarily kill the dad; though the dog is introduced as having killed him, it’s ambiguous.

Aaron: Wait, it is?

Amy: Well, Richard’s mother believes the dog killed him (she also hints, fascinatingly, that the dog might have had *reasons* for wanting vengeance), but the police say he had a heart attack and the dog just got hungry later, after he was dead. Also, to make matters more confusing, the dog is “a different dog” from another dog that visited Clarisse’s house, but has the same name. The dog does EAT THE DAD’S FACE though, either way. Doesn't get much more abject than that. GOODBYE IDENTITY, I'M A DOG AND I ATE YOU.

Jeffrey: The dog definitely ate the face and I blocked it from memory until you guys totally brought it back. (Thanks guys!!)

But the dog does seem to act as a simplification--it is what it is, it doesn’t struggle with identity questions or whether it belongs in any sense of the word. And you can see that in the narrative itself: most of the characters are malleable things locked into an unyielding world, but the dog itself is the immovable object around which the other characters orient themselves.

Amy: Ladivine the First believes that all dogs are dead people trapped in dog skins. So I think you can say the trace of violence is there in its negation, but the dog becomes a protector pretty quickly, though a menacing protector. Up above I call the dog a “haunting trace of racial memory” that “stands for the refusal to participate in any identity formation that relies on erasing an ‘other.’” I stand by that reading, but maybe I want to expand it to say the dog is the negation of identity itself, in some way. For me, when Ladivine is all “fuck it, I’d rather be a dog than like you guys” that’s the novel coming down against identity, at least the way Clarisse Riviere formed hers, and the way Ladivine suggests western identity formation and consolidation works--through violent erasure of the other. Which is why I will stand by my (totally useless) equivocation that Ladivine “both is and isn’t” a passing novel--in America, race and identity mean something very different than I think NDiaye means here, though not unrelated.

Jeffrey: Okay, yes, this comes back to that question of “passing novels.” Clarisse Rivière is the one who finds happiness in passing. But Ladivine Sylla (her mother) just wants her nostalgic dream fulfilled, of being with the man who fathered Malinka/Clarisse and living the ideal of a nuclear family. But as far as I can understand, Clarisse’s daughter Ladivine Rivière is thoroughly--what would be a good word here--integrated? Let’s go with “integrated.” She struggles with being poor, but she doesn’t know that her mother “passed” or ever existed as Malinka, so she isn’t primed to struggle with those identity politics. And so when she sees her children glomming onto that other, classist identity (as Amy discussed above), that triggers a crisis that presumably results in her going mad dog. So everywhere in the book we see passing as a promised land, a kind of Oz that turns out to have a seedy underbelly. When it works too well for Clarisse, the whole marriage falls apart and she goes for Freddy, who is closer to her roots (and, of course, gets on amazingly with her mother) and who eventually brings about her death. Do you guys see Ladivine as an indictment on passing? Everybody does seem to be happy once they pass, or live without the question of whether or not they pass.

Amy: Is Clarisse Riviere happy? I never thought there was any doubt that passing was a horrible soul-death for her as well as an erasure of her mother (and therefore herself). She’s dead from the beginning. She consciously erases her desires, opinions, thoughts, makes her face into a blank with makeup. Her blissed-out life is awful and numb and almost immediately falls through. To me, her murder is the culmination of her self-erasure. It’s self-alienation to the tune of a psychotic break. Ladivine the Younger doesn’t have to “pass”--and we can also agree that one of the themes of ANY passing novel is that “passing” is literally meaningless, because race is dependent on visual markers rather than some essential characteristic--even if she has darker hair than her mother or other physical traits, for all intents and purposes, she’s white. And whiteness is violence, in this book. Being on the side of erasure is violent.

Jeffrey: Oh, so that’s why she was pulling her hair back so tightly it hurt. (It’s an image that’s recurred in some of NDiaye’s other books, and I’ve been curious why it has so much value for her.) It was because she needed to feel some kind of reminder that she was alive, that she was forcing (or numbing?) herself into this shape and identity.

Amy: Interesting to hear that it recurs in other books, Jeffrey--I read somewhere that her weird flower images are also in other books, too. At any rate, I’m pretty convinced that what the book has to say about passing is much more complicated than “it’s a bad idea”--something to do with what’s left over or left out when identities are formed, how identities are formed in the context of violence and erasure--and what’s left over, the abject remainder. The animalistic. What’s disturbing in Ladivine is also what’s brilliant about it, which is the way she cozies up to the abject and animalistic. It’s frightening but it’s preferable to the alternative, which is allying yourself with the violent forces of, because the psychoanalytic reading seems appropriate here, “the name of the father.” The symbolic realm. Language. (Hence the stuttering and falling silent.)

Jeffrey: There’s that silence. It’s so much easier for people in this book to be silent than to talk (or be honest, I mean). When the characters become dogs or even just pass successfully, they go quiet, they refuse to talk about elephants in the room. (Oh shoot, is NDiaye going to use elephants for her next animal transformation? That’s gonna go smoothly oh yes it is.) Anyway, these animals are sort of “othered” but even if they’re silent, they persist and linger in the other characters’ thoughts and vision. They won’t leave people alone, they have to be confronted and grappled with.

Aaron: Which is not only a racial thing, even if it certainly is also a racial thing.

Amy: Well it’s also to do with colonization, which is always about race but not only race. (Maybe race is never only about race.) And it’s about gender, pretty clearly.

Aaron: The word “thing” is making me think of Cesaire and what he had to say about capitalism and colonialism as “thingification.” But again, not only colonialism, though colonialism also; not only capitalism, though capitalism also. It’s all abjection, all remainders, all the way down.

Jeffrey: A digression, but why does Ladivine keep her maiden name all the way through when she's part of the Berger family?

Aaron: I pretty much gave myself permission to lose track of those names, and did. There’s too much to keep track of, too many generations. I know it’s important, and carefully planned out, but it felt like the least interesting part of it all.

Amy: I entirely missed this. I am like, pulling out the novel right now to make sure she’s not Ladivine Berger. Oh god, you’re right. Well, that just means she was destined to melt back into animal-hood all along. I also kept my maiden name, will be transforming into a beast shortly. Woof, woof. <exit stage left>

Aaron: WOOF.