I’ve been following Shirin Neshat’s work for a long time. Initially, it wasn’t by choice: her Women of Allah series was unavoidable. Black and white, clearly confrontational, the images were everywhere, and helped turn the art market towards Iran and its women, and her progression into video art, films always came with admirers and detractors. Neshat was in London for some events, including a workshop and the London Film School as well as a double interview with Isaac Julien at the Barbican. We met over a glass of wine (for her) and an espresso martini (for me), to discuss her latest film with Natalie Portman, the politics of art, and homework.

Tara Aghdashloo: How has your understanding of your background and relationship to your subject matter – which is often Iran – evolved over the years?

Shirin Neshat: The development of the ideas of my work started from the personal to more social, and back to personal. It always relies on where I’m at in my life. To me art is about framing questions. Questions that are really important to the artist. What you question has to do with you and what you struggle with as a human being. These could be existential, political, or things that are from the unknown.

The evolution of my subject and my work reflects the way I navigate in life. If my father dies I think about death, and I make a work about death, like Passage (2001) that I made with Philip Glass. If I’m trying to return to Iran, around 1993-1997, and reconnect with it, then I make Women of Allah, which is a kind of nostalgic point of view of an artist living abroad. When I want to have a sharp knife and be critical about the government, then I make The Last Word, which is a trial. It’s a little bit like music. The artist goes up and down according to the melody and the emotions that drive them to do what they do.

TA: Do you think art is always political, even if you don’t want it to be?

SN: You could say for an Iranian art is always political. And you could say that about Andy Warhol maybe, but I don’t know. If you look at contemporary art and the likes of Jeff Koons or Damien Hirst, it’s not political art. It’s actually very narcissistic and it is the artists’ interest in their own ego. Which a commentary about their own culture whether it’s American culture or Western culture as a whole. If you look at Iranian culture then yes, I could say that every Iranian artist, however they work, somehow it becomes political. Even if they paint flowers it’s political because they are making an effort to move away from the political, and that is a political act.

Do you value political art more than for example, what Jeff Koons does?

Yes and no. For example, I love Lucien Freud for his ability to capture the psychological and emotional angst of human beings. That has nothing to do with politics, it has to do with pure human existence. But then I like William Kentridge and he is not always political but he has done so much work about the apartheid and the South African situation. I could also go for pure aesthetic, like abstract painting.

In Women Without Men there was definitely a strong narrative about a political junction in history, but it was still very artistic in its cinematography and presentation. What do we expect from your future films, and the new one coming up with Natalie Portman?

I don’t even know it myself. For me art and making films is not a strategy, it’s like reacting to what comes your way. And what comes your way in your personal life experience and also the chances you get as an artist and also important political social issues. I make the Book of Kings because I reacted to Arab Spring, but I make Illusions and Mirrors with Natalie Portman, which is very existential and personal.

Subject matters just sort of cook inside you, and you know it’s there and you have to do something about it. Sometimes it’s very rational, like I had a lot of thought about the Umm Kolsoum film (Egypt in My Heart, 2011), but the thing I did with Natalie Portman came out of the blue. It was like a sketch, like a little poem.

Why did you pick her?

I didn’t actually seek her out. It was a commission by Dior, because she’s their muse, and they wanted to do a show about Miss Dior but for her to collaborate with an artist, and she chose me. I was very flattered to have this opportunity and to have a little budget. For me it was a challenge. I’m generally not into stars.

You’ve lived outside of Iran and you just mentioned that where you live as an artist can influence your work. Yet you’re still very much in touch with Iranian colleagues and culture…

I’ve lived in the West longer than I have lived in Iran, so there’s a part of me that is definitely more Western than Iranian. And then there is a part of me that is definitely more Iranian. Iranians give me a sense of security and comfort, but the Westerners give me a sense of who I am. Even if I really tried to I will never completely be in a homogenous community.

That’s interesting, about security and sense of who you are. You could say that Iran doesn’t necessarily inspire security and I think in a Western context no matter how Western you feel you are always a foreigner.

But I’m not. I’m not a traditional Iranian woman. I came to U.S. in 1975 and I met Shoja in 1989 – until then I hadn’t really spent time with Iranians so it only turned after I met him. One of the reasons that I can relate to Shoja [Azari, artist and her long time partner] as someone who I’m with all the time and collaborate with is that he also came to U.S. so long ago. His identity is also not entirely Iranian. For me at the beginning it was difficult to engage with Iranians because I felt so distant. Now I feel great because that gap is gone.

And you mention in another interview that there are new definitions of globalism and now identities are not as stable or stagnant—

Influences define who you are. And it’s different from person to person, and for artists your work will be depending on the life you’re living. So my work has to be only seen through that lens of my personal experience, but not through any others because it won’t work! And the problem with the critics is that they don’t understand that.

Some criticize you for not living in Iran and having subject matter that is Iranian.

That is one of the most stupid criticisms, because it’s like if you’re outside Iran you have no right to it. You know they say you can take an Iranian out of Iran but you can’t take Iran out of an Iranian. To deprive someone of their history and their past and their cultural background because you’re not physically there, it’s like a dictator who is saying you can’t have access to this because you’re not here, so hands off!

In the past couple of years Iranian women have really been entering the international art scene, exhibitions, and biennales. You were one of the leading ones. What do you think about this emerging scene?

I just came from a show of Middle East and Arab artists in Boston, and it’s a mixed blessing. It is bad because it’s the most simplistic context. I can see why so many people would criticize it—I would criticize the show. They had borrowed one of my works and I went there to give a lecture. On the one hand it feels liberating, but on the other hand to group the artists because they are women and from a certain area is wrong. I’m not sure if each one of those artists understands how they are being packaged. I’m a bit older, more experienced, and I’m luckily outside of that pigeonholing, so it won’t hurt me to participate. In fact it would be arrogant of me if I didn’t because it would mean that I think I’m above this.

So is it a foreign, exotic look on the women of the Middle East?

There are things to admire about a show like that because they give a chance to see women’s points of view. But are they really great works of art or is it just subject-driven? And is the perspective very interesting? I’m not sure if it’s so interesting. A lot of Iranian artists are guilty of participating in this whole mishmash that is market-attractive works that also try to be subversive.

How do you think as an artist you can maintain your independence from this? Because some artists may not even be aware that they are being packaged and marketed like that.

Yes, it’s hard, because they are so young and so desperate to get out and I understand that. Because there’s so much press and a large audience.

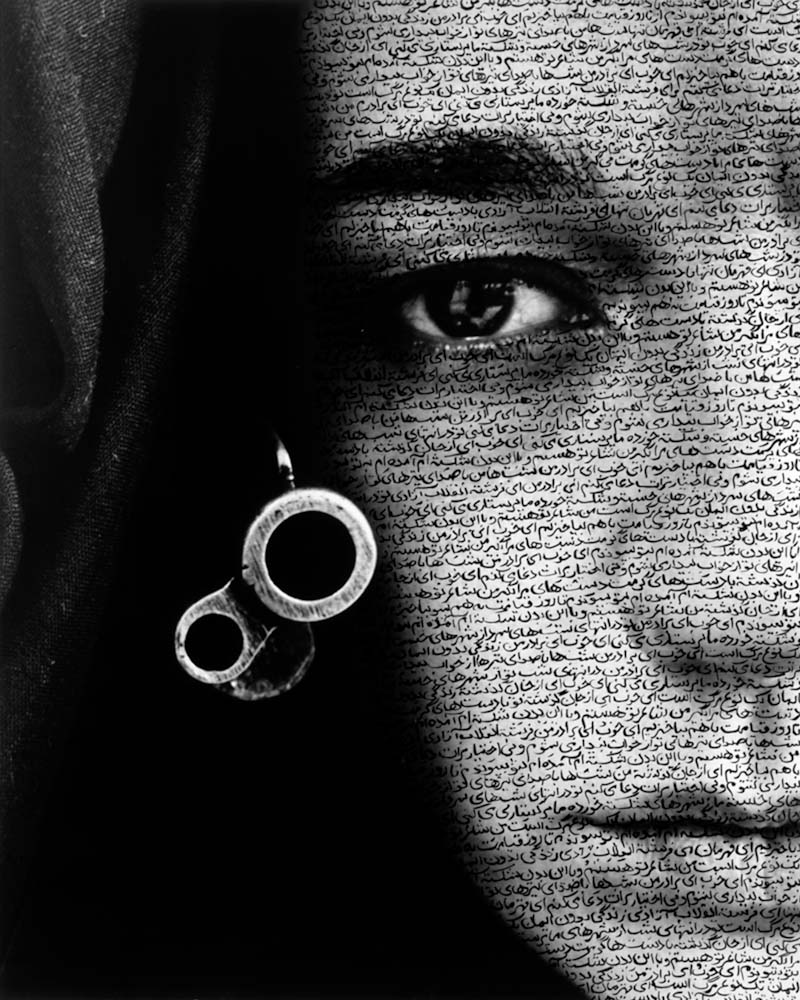

There’s a strong presence of text and poetry in your works, and in the latest photography exhibition you had in New York City. Do you handwrite them? Where do they come from?

Those poems are by famous poets, from Shamlou to others, and we go after pieces whose meanings relate to the images. I have two assistants that help me seek them out. The aesthetic and design are directly taken out of Shahnameh [a long, epic Persian poem written in 935–1020 in Iran]. The images of the war were painted on the bodies.

I do all the more complicated work. My assistants do the paintings and the pen writing. The Book of Kings at Barbara Gladstone [NYC] was 65 photographs, so I couldn’t possibly do them all. And if they sell, I have to go back and re-do it.

That reminds me of writing your homework, or ‘mashq’.

Yes exactly, that’s really what it is. And sometimes my fingers really hurt, because it’s just so painful.

But isn’t it also meditative? Calligraphy in general?

It is. Especially since I usually work with film, and then I come to do this, which is a very solitary experience. I like the contrast of working with my hands vs. working with a team.

You’re one of the first people to use the veil as a symbolic representation, or a code, in your earlier series. Over the years a lot of people have repeated that. What’s your take on it?

I did it very specifically for the time being, and that was my curiosity about the Islamic revolution in Iran. I’ve been accused of exotifying it. The truth is no matter how you look at it, it is what it is. To the eye of the Westerners it’s still exotic and you can’t change the Orientalist point of view— there are all these very serious issues and the veil is what they zero in on. I always say if there was a concern for Middle Eastern women, that’s not the top priority. Maybe because it’s a very visual thing, or a mysterious thing, so it’s endlessly more interesting to the Western eyes. Many people thought I did it just to serve that kind of gaze, but it wasn’t. Women might wear the veil for different reasons.

Well, it’s a successful model that many people use as a short cut.

Yes that’s the word. And they’re not the only ones, but also the market and curators and collectors. Even the use of calligraphy—everybody is writing on every single thing.

You’ve been here for a filmmaking workshop and some lectures. Now that they’re all over, what would be your one advice to young filmmakers?

What is so compelling about your story? Why should anyone care? And a lot of people go back to their families and background. But what is so special about that other than the sentimental value? In art schools I notice that everybody is photographing their family. It’s become an obsession with people because they think all they have to do it to look inside. And I’m saying, come on, you have to do a bit more work.