To be not a man, but the projection of another man’s dreams—what an incomparable humiliation, what vertigo!

—Jorge Luis Borges, The Circular Ruins

Coachella. Tupac. Hologram. Taken apart, none of these things are new, or even revolutionary. But something fascinating happened after the debut of the Tupac hologram (henceforth: Holopac) at Coachella: people were, for however briefly, awestruck. Tech bloggers raced to uncover the “Oz” behind Holopac, only to discover that it is basically the modern version of a 19th century technology called “Pepper’s Ghost.” Keith Wagstaff at Techland explains that “at Coachella, they achieved the effect by rigging up a custom, 30-foot-by-13-foot screen that could be lowered in seconds for a hologram that’s slightly more advanced than Disney’s dancing ghosts.” (Here is an easy, explanatory infographic.) Holopac was an expensive, not-even-new illusion. On cue, talk of taking Holopac on tour and creating new holograms emerged instantaneously, before his holo-drops of sweat had even begun to dry. (Entertainment Weekly has already compiled “Ten Hologram Tours We’d Love to See.)

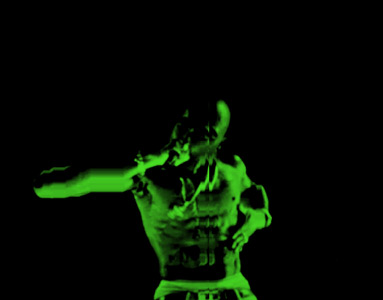

But still, this first incarnation of the ghostly, godly Tupac, rising barechested and glowing over a desert of people, under a sinister fog of marijuana smoke was impressive, a manufactured resurrection that somehow felt authentic. And with posthumously released albums titled “How Long Will They Mourn Me,” “Resurrection” and “Still I Rise,” could there have ever been a more uncannily-primed hologram? A Marvin Gaye or Jimi Hendrix hologram wouldn’t likely evoke the same “I can’t believe my eyes” reaction. Gaye and Hendrix are pretty firmly dead, whereas conspiracy theories still swirl around Tupac that he is living it up, smoking weed and drinking Hennessy in the Caribbean, laughing all the way to the bank. Seeing the Tupac hologram, an eerie sensation arises that it just might be the real thing.

Imagine, for a moment, that seeing Holopac was to be a singular, never-to-happen-again experience. No singing, dancing optical illusion touring stadiums worldwide. Would it then be this generation’s equivalent of being able to say you were at Woodstock, Altamont, the opening night of “The Rite of Spring”? A “you just had to be there” moment in cultural history? Even asking a question like that tells you that we are long past the concept of an exclusive experience that can’t be relived through video or virtual experience. Dr. Dre emphasized that Holopac “was done strictly for Coachella 2012, just for you,” as though sensing the collective yearning for a uniquely experienced moment. But what does it even mean to be “present” for a cultural moment now? Tupac rapping about the halcyon days of the early 90’s may represent a bygone era, and yet Holopac epitomizes the way a generation has been primed to filter most experiences through a tweet, video, or status update (something the Coachella organizers surely banked on). It’s increasingly easier to watch an “exclusive” moment online, then close the tab with the satisfied belief that we too experienced it. We are no longer the protective owners of one-of-a-kind experiences.

We are the latest generation (though certainly not the first) to have our nostalgia commodified, and Holopac seems to be as defining an opening moment for it as any. As we cross some nebulous adult threshold and look over our shoulders at a younger generation growing up with highly manufactured musical artists, the ghostly particles of Holopac conjure up an oddly simpler time, when rappers could be thugs and sing about how much they love their mommas. For those who were drawn to Coachella for its headliners, Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg, it seemed a way to commune with our former selves, selves that remember what it was like to truly discover something pre-viral internet, to truly feel an invested ownership of an artist. And perhaps it goes even deeper than that. Tupac represents a pre-9/11, pre-recession era, and he co-existed seamlessly with artists as diverse and dynamic as The Beastie Boys, Bikini Kill, and Nirvana. It’s surprising that such a notoriously skeptical generation seems to have embraced (or at least not dismissed outright) Holopac.

As a culture we are seemingly obsessed with authenticity, but it’s not clear what an authentic hologram could actually be. In his prescient 1985 novel White Noise, Don DeLillo wrote, We’re not here to capture an image, we’re here to maintain one. Every photograph reinforces the aura. Can you feel it? An accumulation of nameless energies. We are only projecting meaning and memories onto Holopac, onto this swirl of light waves and dust particles. But what are we even cheering when we clap for Holopac? Who reaps our catharsis, our collective suspension of disbelief? Bring the house lights up, and all we are left with is an empty stage, no true symbiosis between artist and fan. Holopac only lets us reinforce the aura of our youth, he is a collision of time standing still with technology unfathomably speeding up. Perhaps we are so obsessed with authenticity because the distinction between real and simulated has become so bizarrely blurred, in a way DeLillo only vaguely anticipated. In his essay “Simulacra and Simulations” Jean Beaudrillard discussed the uneasy handshake in accepting that we are no longer as concerned with separating meaning in the real from the unreal:

The transition from signs which dissimulate something to signs which dissimulate that there is nothing, marks the decisive turning point. The first implies a theology of truth and secrecy. The second inaugurates an age of simulacra and simulation, in which there is no longer any last judgment to separate truth from false, the real from its artificial resurrection, since everything is already dead and risen in advance.

Holopac has truly inaugurated an era that uses artifice in an attempt to capture authenticity. But I say let Holopac rest in peace. Let us have a last-gasp, never to be relived moment of awe and uncertainty. Let us have possibilities and speculation. Let us leave Holopac to wander the deserts of Southern California as a shirtless specter that only appears in certain slants of light during rainbows, or let him possibly be sipping on his beloved orange soda while he records more posthumous albums.