Alison Bechdel may well be the most important cartoonist working today.

With the publication of Are You My Mother?, her amazing new memoir, Bechdel exceeds the considerable achievement of her 2006 masterpiece Fun Home, bringing psychic life to the page like no one else and finding innovative pictorial ways of mixing narrative accessibility with theoretical sophistication.

Artists like Chris Ware and David B. are arguably more masterful at the drafting table — their lines are more amazingly controlled and their cartooning more proficient — but their drawings can overwhelm their characters and stories, which occasionally come to seem like victims of their technical mastery. Their works are objects — beautiful, masterfully crafted, but also fetishistically, virtuosically static, almost cold in their perfection.

By contrast, Are You My Mother? dissects a living, still-beating relationship, rigorously, unsentimentally, confronting the fact that "the story of my mother and me is unfolding even as I write it." What this means is that Bechdel's story has the disorienting gravity of experiences not yet assimilated into any simple symbolic matrix. The challenges this open-endedness poses to the reader are considerable, but the pleasures and insight available for those willing to follow her mind in motion are, correspondingly, without equal.

The opening of Are You My Mother? — which depicts a curious action scene — offers a perfect example of Bechdel's method. In these first pages, Alison practices telling her mother she's writing a memoir about her father; that is, she’s telling her mother about what will become Fun Home. In captions, meanwhile, Alison metafictionally reflects on her struggle to narrate the beginning of the story of her relationship with her mother, to narrate the beginning of the new book we're holding in our hands. Alison concludes, "The real problem with this memoir about my mother is that it has no beginning."

Suddenly, a truck swerves in front of her, almost killing her. Certainly, the unassuming reader thinks, the "literal" level of the story — the proper action — is ready to take priority, to get into the driver's seat, so to speak, leaving behind Alison's metafictional ruminations. But this expectation is immediately dashed when it's revealed that the truck that almost struck Alison is a Stroehamm Sunbeam Truck, the same type that killed her father. "After such a curiously literal and figurative brush with death," the next caption reads, "telling my mother about the book loomed rather smaller."

The difference between writing about getting hit by a truck and writing about the symbolism of almost getting hit by a truck — the difference between a literal and figurative "brush with death" — is the perfect emblem of the difference between Fun Home and Are You My Mother? In Fun Home, the truck hits Alison's father, motivating a sort of illustrated detective story, an inquiry into whether his death was a suicide or an accident. By contrast, Are You My Mother? insists on being a metabook, telling the story of how writing Fun Home affected Bechdel’s relationship with her mother alongside the story of her struggle to write the new book. (Art Spiegelman did something similar in Maus II, which didn't just continue his father's story but wrestled with the success of the first volume.)

Meta-reflection is always tricky, bearing the risk of getting bogged down in self-referential gimmickry. Bechdel pulls it off masterfully. In her new book, thought, action, symbolism, history, memory, and scholarship weave together seamlessly, none taking priority for long, each perfectly balancing the others. Bechdel oscillates between memoir and essay, transcending both genres, accomplishing something that arguably only comics can achieve. This makes Are You My Mother? more challenging than Fun Home, and some mainstream reviewers have already publicly struggled with its complexity. In The New York Times, Dwight Garner wrote that it's "not nearly so good" as Fun Home, complaining that "its tone is therapized and flat," that "there's no real narrative."

Yes, Garner completely misses Bechdel's point — after all, the lack of narrative, the impossibility narrating family history is precisely the subject of the memoir — but it's not hard to understand why some readers might react this way. Fun Home was, after all, relatable. Formally, the family's restored rural Pennsylvania home organized its page layouts and design, making it a sort of paper house, a comforting companion, a graphical rendition of intimate space. Her father’s literary tastes generated a matrix of familiar allusions (to F. Scott Fitzgerald, James Joyce, and Albert Camus, among others), providing another anchor for interpretation.

Are You My Mother? is not exactly relatable in the same way, a fact Bechdel acknowledges from the very first pages. Early on, speaking of the memoir we're holding in our hands, Alison's mother notes that Alison is probably trying to juggle too many strands. "Narrative is what they want," Helen says. It's hard to disagree. This is usually what hypothetical "general" readers want, and some readers (like Garner) will surely grow frustrated with Bechdel's nonlinear and densely allusive mode of storytelling.

Which is a shame, because Are You My Mother?'s agonized search for a form is part of what makes it a masterpiece, the perfect companion to Fun Home's more relatable pleasures.

Ostensibly, Are You My Mother? tells the story of Alison's uneasy relationship with her mother, Helen; her feelings of being emotionally hobbled or crippled; her sense that she had to be the mother to Helen. Though Alison claims that her relationship with Helen displays a "pattern of mutual, preemptive rejection," "each of us withholding in order to foreclose future rejection," it's often hard to pin down the precise cause of her anger. The origins of her agony remain elusive, vague. At times, Helen seems downright nice.

Knitted into this mother-daughter story is Alison's engagement with the ideas of British psychoanalyst and pediatrician Donald Winnicott. "I want him to be my mother," Alison confesses to one of her therapists. Although the memoir includes long reflections on the writing and life of Virginia Woolf, recalling the modernist pantheon that dominated Fun Home, Winnicott is the main reference point in Are You My Mother? Later, in some of the book's most emotionally affecting scenes, we also meet two of Alison's therapists, Jocelyn and Carol, who become prominent characters, alongside a panoply of Alison's long-term partners, who receive less attention. Of Jocelyn, Alison writes in her journal, "So I want Jocelyn to be my mother. Totally. I completely admit it."

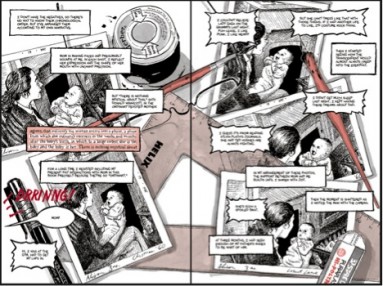

Obviously, then, the question in the title is not so easily answered. Who can be said to be whose mother is the book’s central drama. The possibilities seem endless. To try to answer this question, Are You My Mother? juggles multiple stories in every chapter, mixing narrative scenes (depicting Bechdel, her mother, Winnicott, Woolf), dreams, long excerpts from books, diagrams of Winnicott's ideas, and meticulous hand-drawn reproductions of photographs. As a result, Bechdel's pages are clotted —intentionally so. At times, caption boxes, dialogue bubbles, and the represented action tell three or four divergent stories. This may sound like an exercise in laborious self-consciousness, but Bechdel is such an expert cartoonist that it works effortlessly, which is not to say the book is always easy to read.

Every chapter begins with a dream that offers an organizing set of images for the pages that follow, a structure that recalls Winsor McCay's classic broadsheet comic, Little Nemo in Slumberland. Bechdel radicalizes McCay's buoyant dream logic, as if the final panel of a Little Nemo strip, the recurring moment where our pajama-clad hero falls out of bed, were to become the basis for an entirely new comic exploring his fall in minute detail, exploding his myriad torments and self-doubts, and documenting long sessions with his analyst trying to make sense of every terrifying candy-cane forest and talking dinosaur encountered in Slumberland.

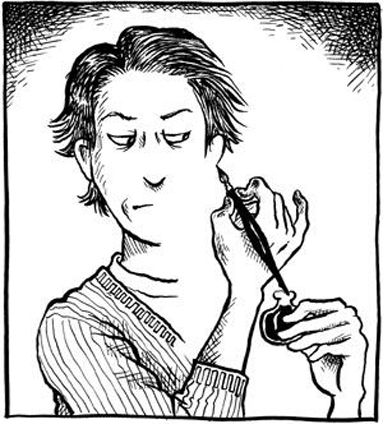

The drawings of Are You My Mother? are rendered in the mature style Bechdel developed for Fun Home and used in the introduction to The Essential Dykes to Watch Out For. Her figures are slightly cartoonish but controlled, the product of an obsessive drafting process in which she takes reference photos of herself posing as every character. Such care gives her figures a naturalistic grace and an emotional intimacy conveyed in tiny, almost subliminal gestures. When photographs, maps, or other primary-source documents appear in the story, as they frequently do, Bechdel draws them by hand, using heavy crosshatching to simulate shading rather than using color, setting them apart strongly from the other drawings, a documentary style she uses to signal that the images are meant to be scrupulous reproductions of real sources; likewise, she often incorporates primary texts into her panels, hand-drawing and lettering them. Given this emphasis on her hand — on the intimacy of touch — it's noteworthy that Bechdel uses a computer font derived from her own drawn letterforms for her lettering, though most readers won't notice this tiny deviation from her painstaking style.

For the main figures, Bechdel uses a gray ink wash and, in Are You My Mother?, red spot color. The resulting emotional environment is less tranquil than the funereal gray-green world of Fun Home; it’s as though the whole world of Are You My Mother? were overheated, about to fly apart. This tightly coiled energy is not a bad thing, given that, as Bechdel has acknowledged in interviews, Are You My Mother? mostly depicts people on the phone, sitting behind their computers, or talking to each other. How else to make this visually interesting? At the level of the individual panel, the drama of Are You My Mother? involves seeing how Bechdel has managed to give expressiveness and energy to essentially static scenes — a drafting process that might be viewed as an allegory of how she's trying to enliven her chilly relationship with her mother.

The opening dream sequences, like the near-miss with the truck, add movement and physical action to Bechdel's introspective narrative. Likewise, diagrams and commentary cram busily into individual panels, invoking the manic spirit of Harvey Kurtzman and Bill Elder’s hyperdetailed MAD comics.

Compositionally, her pages often incorporate multiple styles into a unified narrative frame, finding a form for the convulsions of Bechdel's mental life. For example, the first chapter culminates in an emotionally walloping spread showing a sequence of snapshots of Alison's mother holding her as a baby. They have been ordered on her desk to tell a story, accompanied by snippets of Winnicott's writing, present-day dialogue with her mother, and metafictional captions. In the lower-right quadrant, baby Alison comes to realize that she is being photographed and looks suddenly alarmed. Closer to the corner, an eraser reframes the page into a trompe l'oeil rendition of Bechdel's desk. The movement of her mind is frozen and gorgeously depicted. Only comics can do this.

Paradoxically, what Bechdel's depiction of her mind uncovers is that the mind is always vanishing from view, defining itself through its relationships to others.

As this discovery plays out, it allows Are You My Mother? to transcend its straightforward mother-daughter story and turn it instead into a profound meditation on the psychoanalytic idea that the self is always relational. Bechdel explores what it would mean to take seriously Winnicott's riff on Descartes: "When I look I am seen, so I exist." In other words, the ego is not autonomous or set off with firm boundaries but is always in relation to other similarly situated non-autonomous selves. What we are is our relationships with others, an infinite set of transferences. Bechdel describes transference as an "alchemical power"; it "essentially turns one person into another."

This can sound convoluted in theory, but the relational constitution of identity is a mundane affair, both in Alison's ordinary life and on the pages of Are You My Mother? For example, while talking with her mother on the phone, Alison automatically transcribes what her mother says onto her computer, paying attention primarily to the fidelity of her recording. This, like her reference photos, is partly a function of Alison's mania for self-documenting, but it also dramatizes the circuit of the mother-daughter relation. Helen performs a similar service, transcribing Alison's diary entries for her when she was a child. "My mother composed me as I now compose her," Bechdel writes. The irony, of course, is that when she transcribes her mother's reflections, she's not listening to her mother's words but becomes a mere a conduit for them. Likewise, young Alison thinks that she's getting her mother's undivided attention when Helen transcribes her journal. In trying to relate to each other as subjects, mother and daughter each turn the other into an object — an all-too-common parent-child dynamic.

Bechdel takes this seemingly ordinary observation and makes it strange; she uses the story of her objectified relationship with her mother to reflect on the nature of her work as an artist and, ultimately, to dramatize her memoir’s ambiguous place between subject and object. Alison sends drafts of chapters to her mother, worrying with her on the phone about whether the book holds together. Helen gives her approval finally, saying "Well, it coheres" and suggesting that "it's a metabook." Indeed! With her therapist, Alison complains, "Why can't my life and my work be the same thing? My work is about my life." The therapist responds, "The thing is, you relate to your own mind like it's an object," as if it were "an internalized parent or lover." In a caption box, Bechdel reports, "The irony of the fact that I'm writing a book about all this is not lost on me. Yet I don't seem to have a choice." What is at stake in Bechdel's exploration of mutual mother-daughter objectification — and her emphasis on the memoir's unique position between subject and object — is the very possibility of communication, not only with her mother but also with the reader.

As Bechdel strives to put her work and life into an ordered relationship, Winnicott's notion of a transitional object becomes important to her. The transitional object is a "special possession [babies use] as they learn they're separate from their mother" — something like a stuffed toy. These objects are "not 'me,' but not 'not-me,' either." Bechdel clearly wants this description to apply to her book; she wants her book to become an object that she can use to separate herself, in a performative fashion, from her mother. By turning her life into an object, she suggests, she might finally be able to finally overcome her anxieties and pain. As she puts it near the end of the book, "I have destroyed my mother, and she has survived my destruction." Doing so, she hopes, will allow her to relate to her mother in healthier ways.

And so, whereas Fun Home was a blue-green-tinted house, Are You My Mother? is a red-hued transitional object: in Winnicott's sense, a semi-sentient object addressing the reader as though the title were in fact the book's question to us or the question we are asking the book. Bechdel is interested in the "place between the subjective and the objective," the transformation of persons into things, and the transformation of things into people. One reason her comics are so successful is precisely because comics as an art form stand precisely between those two poles. Comics combine the urgency of the image with the intimacy of the page, the concreteness of the object with the fluidity of the subject. Few creators have the power or skill to fuse urgency and intimacy, outer and inner, action and thought, object and subject. Bechdel does.