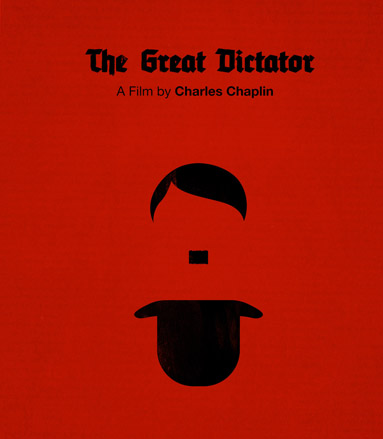

First, some context. Born four days apart, Hitler and Chaplin are the two faces of the 20th century: the genocidal fascist tyrant and the lovable, socialist clown, both movie stars in their own ways. The Great Dictator is a satire in which Chaplin plays both his trademark Tramp—here reimagined as a Jewish Barber in the fictional country of Tomania—and Adolph Hitler—here reimagined as Adenoid Hynkel, Dictator of Tomania. The film began shooting six days after the outbreak of World War II in a hostile climate: Hollywood refused to risk export profits on openly anti-Fascist films and isolationism held sway in Washington. FDR himself sent words of encouragement to Chaplin. Released in 1940, The Great Dictator was a blockbuster in America and Britain, though it would be another year until America entered the war. It was banned in the Reich, like all of Chaplin’s films (the Nazis thought Chaplin was a Jew), but Hitler had it screened for himself twice. Chaplin later said that if he’d known the full extent of the Holocaust he could not have made the film. It was Chaplin’s first film with synchronized sound, and his last to star the Little Tramp.

The whole of The Great Dictator, its triumph and its failure, can be understood in miniature in one scene. Thirty minutes in, Charlie is chased through the ghetto by Nazi stormtroopers. Charlie’s sweetheart Hannah (played by his real life half-Jewish wife Paulette Goddard) comes to his rescue with a frying pan. Predictably, she knocks Charlie on the head too. The stormtroopers go down and Charlie goes balletically stumbling down the street in a post-concussive haze. It’s a classic gag, but here’s the real joke, the one that sticks in your throat: Charlie careens down the sidewalk in one long tracking shot, and passes by storefront after storefront, all defaced with the same graffito: “Jew.” It’s a conceptual zoom-out in which ahistorical slapstick finds itself set against the single greatest atrocity in history. The real farce is not the fictional one, but the historical one: not the misadventures of Chaplin’s Jewish Barber, but the misadventures of Charlie Chaplin making this film, a masterpiece of comedy and sentiment, while perfectly ignorant of the worst thing that ever happened.

The Great Dictator is about its time but very much of its time. What it gets wrong is as informative as what it gets right. It was the only contemporaneous Hollywood film to cast light on the oppression of Jews, and it did so, as critic Richard Brody argues, better than most documentaries later would, showing us the full range of anti-Semitic violence, from daily humiliations to mob violence to concentration camps. However, Chaplin underestimated the centrality of anti-Semitism to Nazi ideology, presenting it as a mere ploy to distract the German people from economic hardship: about halfway through the film Hynkel instructs his advisor Garbage (Goebbels) to call off violence against the Jews while the Reich barters a deal with a Jewish banker.

Real life anti-Semitism was nowhere near that cynical—it was the beating heart of Nazi politics, much more insidious than a ploy of power-hungry bureaucrats. Chaplin couldn’t imagine the gas chambers, but then maybe no decent person could. That is why the most poignant moments in the film’s depiction of anti-Semitism are those which take on new meanings with the benefit of hindsight—incidental lines where Hynkel’s advisors say that they will “kill off the Jews” and that they have “discovered the most wonderful, the most marvelous poison gas. It will kill everybody.” It is as though the film’s unconscious were crying out, giving voice to the darkest, suppressed fears of just how far the oppression of Jews could go. These lines make us wince: Chaplin was so close, yet so far.

For a film about Jews, The Great Dictator is remarkably goyish. You will not hear a word of Yiddish nor a note of klezmer. You will see Hebrew lettering Exactly once; the rest of the text on the “Jewish” storefronts are in Esperanto. There are no yarmulkes, no payis, no temples, no prayers, in short, no Judaism. As much as this film is about Jews, it’s much more about Americans. When you watch this film, one way you should watch it is as propaganda, designed to urge the United States to war against Fascism.

Bask in its total Americanness. The Tomainian ghetto is the universal slum of all Chaplin’s films, as easily Boston as Berlin. When Jewish characters talk of dying for their country in the fight against fascism, the words down much easier if you understand them as being spoken by Americans to Americans. As the ghetto burns, Hannah’s pep talk to Charlie should sound familiar: “We can start again. We can go to Austerlich [the fictional stand in for Austria], that’s still a free country. […] It’s beautiful there: wonderful green fields, and they grow apples and grapes. [...] If we work hard and don’t eat much, we can save money, buy a chicken farm.” It’s Manifest Destiny. When Chaplin’s Jews escape across the border to Austerlich to work on what is clearly a vineyard in southern California, you might as well be watching Grapes of Wrath (also released in 1940).

To convince Americans that Hitler could be easily defeated, Chaplin portrays him as an incompetent buffoon, the puppet of more sophisticated advisors, and a dwarf in the shadow of Mussolini. This is funny, but it’s really incorrect, and when you think about how incorrect it is, it’s kind of gross. Chaplin began to recognize this himself while shooting the film: after the invasion of France, Chaplin was quoted as saying, “Hitler is a horrible menace to civilization, rather than someone to laugh at.” The virtuosity of Chaplin’s performance as Hynkel is distracting. We never really recognize Hitler the historical figure in Hynkel because we can’t get past watching Chaplin. Never, that is, except for in the famous scene where Hynkel cavorts through his office while playing with a helium-inflated globe and daydreaming of world domination.

It is very important in this sequence that Hynkel is alone and that he is silent. This is a private reverie. He’s not performing for anyone else. We are watching pure self-expression, pure freedom. Hynkel dancing on his toes, tossing the globe from hand to hand, effortlessly bouncing it into the air, it floating back down to meet him: the lightness of these gestures, the sheer joy and beauty of them! It is the same bodily grace that elevates the Tramp above his poverty, but here it is monstrous. It reminds us that fascism also speaks the language of freedom—the “freedom” of the powerful to dominate the weak, the “freedom” of state and corporation from the claims and desires of individuals. The Nazi Party sees itself as “freeing” the German people from the yoke of international Jewry, socialism, homosexuality etc. When Hynkel dances so lightly, so comically, with the entire world hanging in the balance of every gesture, it underlines that power experiences itself as freedom, evil experiences itself as joy. If this scene humanizes a monster, it does so by showing us something monstrous about humanity.

Chaplin realizes this, and the ambiguity only deepens in the film’s ostensibly triumphant conclusion. At the end of the film, the inevitable happens: in an improbable case of mistaken identities, Hynkel and the Barber switch places. Hynkel is accidentally arrested by his own soldiers, and the Barber is whisked away to Refenstahlesque rally to give a speech after the invasion of Austerlich. For four minutes, Chaplin addresses the camera neither as the Barber nor as Hynkel, but as himself, in a passionate plea for peace, understanding, and human decency. It is one of the greatest and most moving speeches in cinema.

Chaplin’s vision for world peace is distinctively of its time—a blend of cosmopolitan liberalism, FDR-style populism, and utopian socialism. Listening to him today you feel acutely how short History has fallen of Chaplin’s dreams. But there’s something else unnerving about this speech besides the disappointments of History. The speech begins with the very same music that played throughout the globe scene, the prelude to Wagner’s Lohengrin, suggesting a parallel between Hynkel’s daydreams of a universal empire and Chaplin’s universalist humanism. This same ambiguity runs through Wagner’s music, which, after all, aspired to be both universal Art and German ethnonationalist ritual. The suggestion is that maybe Art is unreliable as a vessel for politics. If Art, by definition, is always open to interpretation, then even the most humanistic art can be made to serve inhumane ends. While Chaplin speaks of pacificism, his plea ultimately function as a rationalization for just war. Chaplin’s words wash the blood from FDR’s hands.

Chaplin finishes his speech, and the crowd of Nazis cheer just as they did for Hynkel. Did they even understand a word he said? The film cuts away from Chaplin—what happens to him? Do the Nazis throw down their arms and dance in the streets? Is all anti-Semitism, all oppression, all war and exploitation wiped away, all because of Charlie’s speech? It seems unlikely. Of course, this speech isn’t really addressed to Nazis; it’s propaganda for Americans. But it is artistically significant that the speech remains in the world of the film. It’s a fantasy—like humanism. If a Nazi heard Chaplin’s speech, what would he say? Probably, “What a bunch of gibberish.” But, even more troubling, the Nazi might say, “World peace! I agree! That’s why we should exterminate the Jews!” And in fact, in an early draft of the film, the speech was just a dream. In that draft, the applause of the crowd gives way to the reveille of a trumpet. Chaplin wakes up in a concentration camp “with a smile as a stormtrooper enters. Charlie smiles at him. The stormtrooper starts to smile back, then, ashamed at his softness, he bellows: ‘Get up, Jew! Where the hell do you think you are?’”