Rock and roll survives by reinventing, rather impossibly, over and over, that which isn’t permitted. For one more generation, for one more year, for one more album, for one more song, rock music always finds one last rule to break. There’s a visceral exhale when we step over the line. We close our eyes and hold our breath, and it matters again that we didn’t do what we were told. Relief is rebellion; rebellion is relief.

Lately our rock stars are not cool at all, and Arcade Fire, whose latest album The Suburbs was released last week, are maybe even more than any other groups of nice musicians with holes in their sweaters and hearts bleeding on their sleeves very seriously uncool. They’re sentimental and grandiose. They publish liner notes constructed to look like teenage journals. They love their friends; worse, they love their girlfriends; worst of all, they love their families. This isn’t rock-star behavior at all. But that’s how indie rock defines itself, how it breaks with both an earlier generation’s “classic” rock and current hipster culture’s mandated boredom.

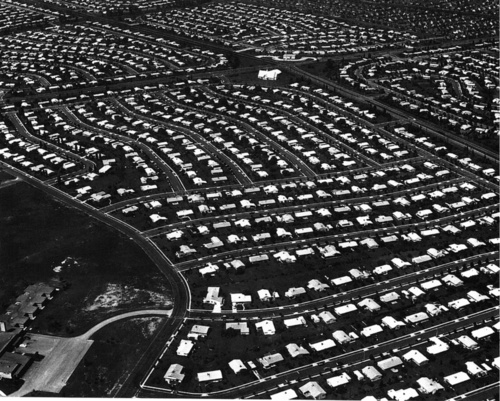

The album performs over and over again that same kind of reversal, substituting familiar mid-American comforts for defiance and rebellion. The line “we will never get away from the sprawl,” returns in multiple and various choruses, but the more it’s brought back and restated, the less it seems to be a cry of despair. Eventually it sounds like a sigh of relief or even contentment instead, giving up and going home. To admit we want all the obvious things from which we were supposed to rebel is itself rebellious. Musical culture starting in the mid-1960s helped to expose the suburban fantasy as a hollow and manipulative myth. But that figuration is somewhat worn out half a century later. It now seems a more disruptive act to admit that the suburban fantasy may have both substance and utility, that it perhaps represents something that we can’t get away from not because it’s culturally dominant but because it’s lodged in our desires and imagined futures. Sweaters and homes and kids and cars and families are the subject of this album, but they’re points of return. Song after song unfurls a guilty but undeniable longing for the sort of stasis and one-dimensional morality against which early rock ‘n’ roll defined itself.

The Arcade Fire are a band constructed from this kind of nostalgia. They are nostalgic for their own past albums, as the lyrical and musical callbacks on this one demonstrate. They are nostalgic for their childhoods and other people’s childhoods. They’re probably nostalgic for things that happened two hours ago. They’re even nostalgic for things they never experienced – the song “We Used to Wait,” is about writing letters and waiting for a reply to arrive in the mail. It’s unlikely that anyone in this band, let alone in this band’s audience, is old enough to actually remember writing and receiving physical letters.

But that’s the point. The suburbs of the album’s title are a nostalgic fiction too. They’re not actually where you grew up. You didn’t actually learn to drive on empty roads between houses in the summer or look for the girl you loved in every passing car. You didn’t even really want to escape your parents’ house. Rather, you heard that this was what happened to all the other teenagers, and you long somehow to recreate those memories — the painful, ugly, weird parts too — that everyone else was having, that everyone was supposed to have. Rock music has always been good at turning the unpleasant into the attractive. The suburbs, the simple, boring, repetitive, stifling, two- kids-and-a-garage house fantasies, are perhaps the most unpleasant thing to the average teenager listening to rock music, so to admit a longing for exactly that simplicity is how this sentimental, optimistic band locates a legitimate rebellion. There might be better, richer, freer worlds out there away from the suburbs, but they’re also far more difficult and complex. The world beyond the suburbs might be more honest, but often it’s a lot easier just to be dishonest. This album admits these rather unattractive longings, and by doing so articulates a small but important cultural secret: sometimes we just want to go home. Sometimes we just want to lie to ourselves that everything really is as simple as a family in an advertisement from the 1950s.

Older rock and roll was about telling Dad to fuck off and driving away from Dad’s house. Rebellion was simple and still new — the music taught us how to do it. But that was the way Dad rebelled against his Dad. Now that the genre has grown up and is as old as Dad, its rebellions have necessarily become more complex, engaged with sadness and ambivalence. Rock music no longer puts us in the car, turns the ignition and sets us driving, free from Dad. Now rock music brings us back to Dad and eventually turns us into Dad.

Arcade Fire is and has always been music about Dad. Funeral, the album that launched the band, was a response to Win Butler’s father’s death. Neon Bibleculminates with a song whose long buildup finally yields to the exhausted, exasperated reprimand of the singer’s father: “Do you know what I was doing at your age?” If Funeral mourned Dad and Neon Bible yelled at Dad, The Suburbsadmits our desire to become Dad. It’s not about the fear of adulthood. It’s about the fear that, in our endless adolescence, in our unwillingness to be happy, in the music that enables our sloppiest feelings and keeps us forever fifteen years old, we may never get to be Dad. It’s not that simple; just becoming Dad doesn’t make one good, or content, or moral, or happy. But we’re tired of telling everyone that we know that unhappy truth; we’d rather admit that although we know, we wish we didn’t know.