Illustrations from The Story of the Sun (1893)

"To travel is to discover that everyone is wrong about other countries." -- Aldous Huxley

Emboldened by the tales of kings Harald and Olaf, of their rude castles perched atop cliffs and their great fleets of small vessels, excited by their feats of valor and violence amid forests and fjords, former Illinois Supreme Court Justice John Dean Caton decided to set off for Norway. At the time of his decision in London for the first leg of what would become a months-long adventure, he asked how a body traveled to this rugged land. Only with difficulty, people told him; not too many journey as far north as he intended.

Unfazed by these reports, the good judge boarded a steamboat that left every other Thursday for Trondheim. He booked the last available stateroom and set sail the next morning. So fine did the weather prove early in the trip that Caton took the air deckside. By evening, however, the wind had increased to half gale-force, and the waves lapped his feet. He retreated indoors, wrapped himself in a blanket, and on the floor of the dining saloon settled for the night.

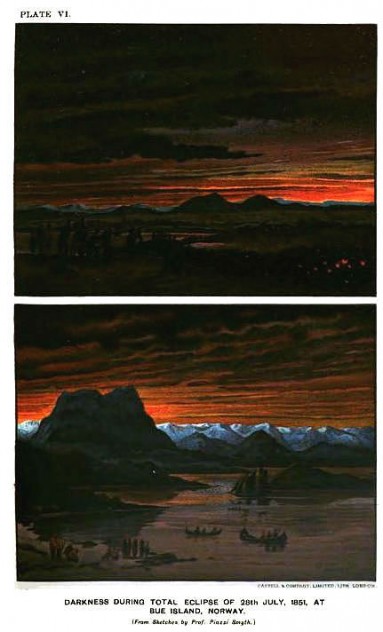

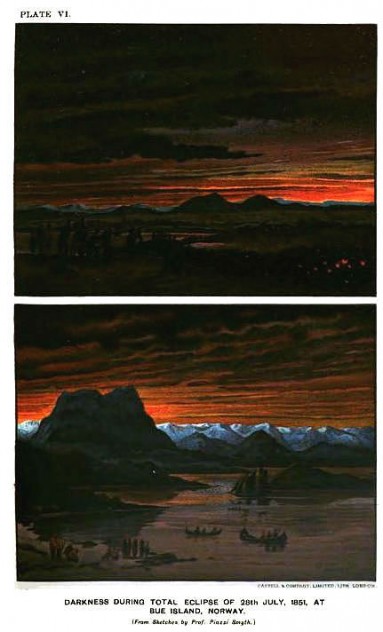

The North Sea lived up to its reputation. It lashed and jostled the steamboat. Morning saw the storm rage on. At midnight the second night, Caton, hazarding a brief peek through a porthole, spied in the distance the snow-capped mountains of Norway awash in light as if it were noon. The midnight sun, he wrote in his memoir of the trip A Summer in Norway (1875), made it seem as if he had landed "at the confines of another world, where the laws of nature as we had always known them, were suspended."

"[The] separation of earth and sky had been accomplished by Shu the god of the atmosphere, who afterward continued to support the sky as he stood with his feet on earth. There, like Atlas shouldering the earth, he was fed by provisions of the Sun-god brought by a falcon." -- James Henry Breasted, Development of Religion and Thought in Ancient Egypt (1912)

Throughout this other world Caton traveled by carriage and by boat. He stopped in towns large and small, noting in his journal the local industry and social customs. The farther north he trekked, the more he longed for darkness. On the longest night of the year he observed among the hills outside of Trondheim crowds of people singing and dancing before great bonfires. So bright was the sunlight that he saw couples steal away from the noisy throng into the forest beyond. For them, it seemed, night without darkness brought joy.

"The Norwegians are not only patient of labour, but ingenious to contrive, and dexterous to execute many feats of mechanical skill. The peasants never employ the hatter, the shoemaker, the taylor, tanner, weaver, carpenter, smith, or joiner, nor do they ever buy any goods in the towns; all these trades are exercised in every farm house, and sometimes with so much dexterity, that their work is scarce to be distinguished from that produced by professed artizans in town." -- The Gentleman's Magazine (1755)

A people capable of such revels had Caton often missing "the stars and stripes," he admitted. He found them polite but grave. Rarely did they talk, and they never laughed. Even the young appeared sober in comparison to their American peers. Their love they reserved for one thing: fish. He saw evidence of this while aboard a steamship headed even farther north. As he sat atop the upper deck, he watched as the islands of the Norwegian coast drifted past. Some were but small rocky knobs, barely jutting above the water, while others spanned miles. Many were covered in thick stacks of codfish, some four feet in diameter and five or six feet high.

Caton found that the codfish stacks strangely resembled haycocks, and he marveled at how the fisherman and their families constructed them. He noted that "real skill was required in their construction; they were perfectly round, and their walls were as straight and regular as possible." Children gathered up the dried planks of fish and their mothers stacked them. Husbands mostly supervised.

"There is never a fish without a bone, and no man without faults." -- old Norwegian proverb

Codfish covered thousands of acres, enough to feed an army. "A piscatorial paradise!," as Caton himself remarked. But when he sat down to his first meal aboard that Norwegian steamer, attendants served him third-rate mutton and rubbery steak. (The potatoes he found very fine.) Other passengers feasted on fish. When he asked why he too couldn't do so, his interpreter told him that the ship's crew only wanted to impress the foreigner. Caton made it clear he wanted to eat like the Norwegians, and from that morning on, fish awaited him at every meal. "I really felt

scaly, and was sometimes almost afraid to look at a hook," he writes of this dietary regimen.

"Here it was where Frithjof gay / Wooed King Belés fair-haired daughter; / Here she sang the sweet, sad lay / Which her love had taught her. // Hence those vikings sprung whose sword / Walked the South from idle dalliance; // Who in Vineland's rivers moored / Dauntlessly their galleons. / Now, alas! that age hath fled, / Fled the spirit that upbore it. / Ah, but still doth midnight shed / Flaming splendor o'er it." -- Hjalmar Hjorth Boyesen's Idyls of Norway (1882)

"FRESH CODFISH, NORWEGIAN STYLE. Raise the fillets from a very fresh codfish; cut and pare them into half heart-shaped pieces, season with salt, pepper, parsley, lemon juice and chopped shallots; lay them in a straight row on a baking dish with their seasoning, sprinkle liberally with bread crumbs, and on the top a little parmesan cheese; pour over melted butter, and cook the fish in a hot oven; serve a separate sauceboat of white wine sauce thickened with egg-yolks and cream, and finished with a little nutmeg." -- From a 1904 issue of the Stewards Manual of the Stewards Association of New York City

Stuffed to the gills with fish, Caton enjoyed the rest of his trip. The steamer stopped frequently at the islands and small coastal towns. Passengers boarded and disembarked. Some bound for a fair farther north brought with them mounds of pickled herring and rye bread for the occasion. As they came and went Caton admired their simple, understated cheer, their desire for conviviality in the boreal wilderness. In their pleasant company he crossed the Arctic Circle just as the midnight sun paused above the horizon before beginning its next ascension; and finally he understood how the constant light could be other than oppressive, could rather inspire a devotion to "wild legends which those who ... lived amid such surroundings, loved to hear and tell and, if possible, to believe."