Walgreens sells cheap plastic ones. Celebrities are buying gold-plated ones. Mass manufacturers like Trojan are giving them away in the streets of New York. The day of the sex toy has come and with it, the walls surrounding our prudish society will crumble. It will be the second coming of love, now freer than ever.

Well, of course not.

Sex-toy companies aren’t setting anyone free or even challenging society's ideas about sex. They are trying to divert us from sex to something a lot more palpable and sellable: pleasure. Lelo, a Swedish company founded by industrial designers, calls its items “pleasure objects” rather than sex toys, while Jimmyjane, a high-end sex-toy manufacturer based in San Francisco, asks on its website, “What's your pleasure?”

Such nouveau sex-toy makers have built a garden, a beautiful place, completely separate from the messy work of heaving bodies, sexism, and history. A pleasure that can be indulged in without shame and without evoking the troublesome history of the practices it is supplanting. A pleasure that's simple. A pleasure that avoids tackling the problem of the power dynamics inherent in sexual relations between actual people.

Sure, sex is pleasurable. Sex can be fun. But sex is also complicated. Power is tossed around the sheets as often as orgasms. Sex-toy marketing attempts to erase those aspects, replacing them with tingles, buzzes, and “oohhhs!” When sex simply equals pleasure, it's innocuous fun, not an emotional minefield. Sex, or something approximating it, becomes easy with a single swipe of the credit card.

When we say “sex sells,” what we really mean is that pleasure sells. Marketers want to let you know that orgasms can be bought without worry over the social dynamics of what constitutes sex, that they can be as simple as an on-off switch. A flip through contemporary television and magazine ads sends a loud message: own your pleasure ? do what you find pleasurable ? buy this. With this messaging, "pleasure objects" are an easy sell. Gender politics, after all, is a lot harder sell than pleasure; it might even require advertising images that don’t depict a nearly naked size 0 body, legs just ever so slightly ajar. Better to make sexual experience seem a pleasure akin to a chocolate bar or a massage, unlike real sex which is always inseparable from power.

***

Sex toys for women aren't meant to be replacements for sex. They're an alternative method to getting the good fuzzy feelings traditionally associated with sexual contact, without the historical pitfalls. When women get marketed pleasure through a sex toy, what they're really being sold is sexual pleasure without the “bad parts” of sex. A tool, specifically designed for delight is there in discrete, chic packaging. Indulge in it. Let it satisfy. Let it cure hysterical needs. Don't even think about that “real thing” anymore because this is better, safer, easier.

But just as customers should be wary of ice cream without calories, there's something about sexual pleasure without the other stuff which sounds suspiciously lacking. Selling products to women for "pleasure" rather than for "sex" helps maintain the separation of the two, as well as the notion that anything that isn’t penetrative isn’t quite sex. That old androcentric model that the only real sex involves female preparation (like she's a chicken about to be roast in an oven), male penetration, and male ejaculation still remains firmly entrenched and uncontested by “pleasure objects.”

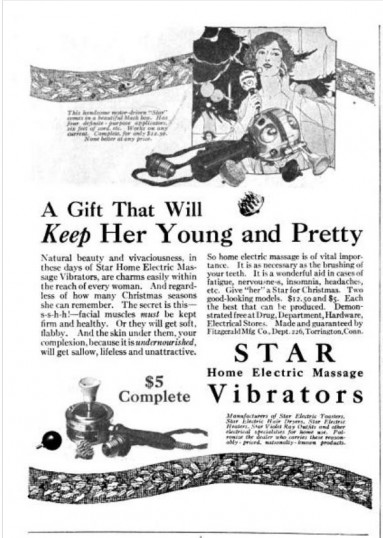

The effort to disassociate sexual pleasure from anything that isn't penetrative isn't new. The vibrator was first developed as a medical device to help doctors — from Hippocrates on — save time and effort in “curing” women of their hysteria. For the Victorians, with all their fears of losing female saintliness, vibrators were acceptable because the models of the era were not penetrative or phallic and therefore not “truly” sexual.

What really riled up the Victorians was the speculum, a medical device that was inserted into the vagina. It was phallic. It traveled up the same walls as a penis would and therefore disrupted the sanctity of the sex act. And the proper people of the day feared that it, in all its cold, pointy metal glory, was being used for masturbation. “Any object or device that traveled the path of the totemic penis into the vagina was, at the end of the 19th century, suspected of having an orgasmically stimulating effect,” writes Rachel P. Maines in The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria," the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction.

With the advent of household electricity in the early 20th century, came personal vibrators marketed for personal care.

However, around 1930, their association with sexual pleasure — and not just, say, innocuous stress relief or beauty gadget to create a glow —became too strong, and they largely disappeared from magazine advertising. While orgasmic glows are a-okay, sexual gratification without a male counterpart was not.

Eventually, as female desire stopped being seen as a deep medical and psychological concern with the onslaught of the sexual revolution, what was once of physician's tool began to be sold blatantly as a sexual device. Feminists, like Betty Dodson in 1974’s Sex for One, began sermonizing about self-pleasure. Vibrators were now urged on liberated women as a means of buying pleasure into their lives — pleasure they might not have enjoyed with a man, within the heteronormative framework presumed universal. It was a separate but equal pleasure, if you will.

***

The market for men’s sex toys offers further proof that the old androcentric model is still as standard as ever and still defines what has been known for thousands of years as “real sex.” Unlike sex toys for women, sex toys for men are designed to replicate the "man enters, man ejaculates" sex rather than offer an alternative. Instead of “pleasure objects,” toys for men are marketed as being like close-as-you-can-get-to-the-real-thing.

Fleshlight, an American company that in 1998 patented a nonlatex, nonplastic, nonsilicone lining for its handheld masturbators, calls its special material “Real Feel Superskin.” The men's section of Adam and Eve, a mega-online sex store and porn producer (with titles including 2005's top selling and most AVN Award-winning film Pirates) proclaims the men’s products to be so good, “You'll think it's the real thing.”

When sex toys appear in mainstream pornography (typically targeted toward men), they are rarely true vibrators, according to Maines. Instead, the sex toy of choice are dildos or vibrating dildos — toys specifically meant to approximate (at least in the universe in which penises are regularly 10 inches long and two inches wide) genitals. Pornography puts the messiness of bodies front and center and emphasizes the significance of male bits — penises and cum — as much as possible. The near institutional use of the cumshot in mainstream porn is just one example. In the world of “hardcore sex” marketed toward men, the phallus still reigns supreme.

But overwhelmingly, phalluses aren't what women use. According to Maines, only 11 percent to 20 percent of women today said they used dildos or vibrating dildos, which includes the made-famous-on-TV Rabbit.

Today, the discerning female customer can choose from vibrators which look like an anime rabbit and an orb that's more evocative of a UFO than a penis. Vibrators are sold as providing a pleasure different than the pleasure a penis provides — different from the pleasure of “real sex.” A pleasure that's more suitable for women because after all, 70 percent of woman don't orgasm from penetrative sex alone.

The shapes of women’s sex toys are not just designed for the promise of maximum physical pleasurability — San Francisco-based Jimmyjane's version of the rabbit vibrator includes independently moving ears and vibrators at the tips of the ears that keep buzzing no matter how harshly it's being shoved in there — but to remove the mental and emotional burden of engaging with a humanoid sexuality. Some toy designers purposely choose anamorphic shapes to avoid mimicking genitalia and protect against the threatening associations such comparisons can create for men. An Atlantic profile of Ethan Imboden, the founder of Jimmyjane noted that some men can be frightened by the thought of being supplanted by a too-phallic toy. “That's an element of why we make the products as quiet as they are,” Imboden told the Atlantic.” It's also why we make them visually quiet."

And women, it seems, also want to be removed from thoughts that they are being penetrated by a phallus. “I believe there’s still a place for the phallus, but women want a design that’s more comfortable,” says Donna Faro of Lelo, in a Los Angeles story. Historically, the phallus has been representative of fertility, prosperity, and power. But the universe of sex toys for women sells a world where that's an unnecessary hinderance on pleasure.

In removing the associations with genitalia, the messiness of bodies mashing together is obfuscated. Men no longer have to worry about being replaced. Women no longer have to worry about the psychic implications of being penetrated by a penis. Society doesn't have to worry about gender norms being disturbed. And expectations of what defines sex remains stable.

While clitoral stimulation gets a well-deserved nod, it’s marketed as pleasure, not sex. It's either a supplement or an alternative to what is still the main event of androcentricity: woman is prepared, man enters, man ejaculates. No clitoral stimulation required. Pleasure for pleasure's sake: it's a market solution consumers can have orgasms over.