This post is the first in a series of articles that explore the stories behind history's more peculiar cookbooks.

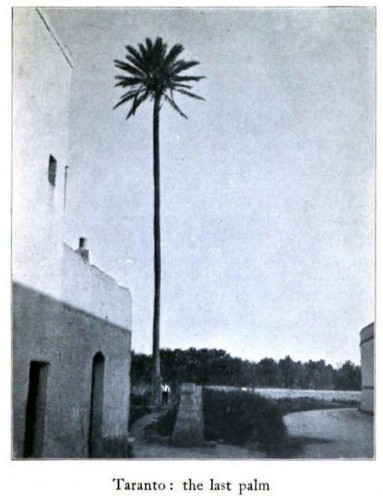

The courtship rituals of Southern Italy captivated the writer and notorious sybarite Norman Douglas. Each evening he watched as young Calabrian men would lean against the railing of Corso Vittorio Emanuele, a promenade that skirts the south side of the old town, their backs to the sea and their eyes fixed on the houses across the road

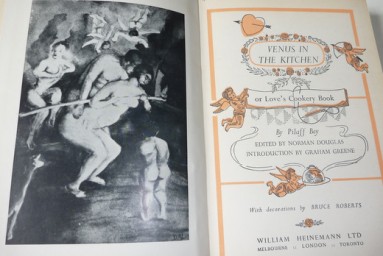

"Youth must keep up the poetic tradition of the 'fiery,'" Douglas surmised. Perhaps he had this tradition in mind, and the foods that could sustain such vigils, when he penned his final work, the 1952 cookbook Venus in the Kitchen. Containing recipes alternately delectable, prosaic and bizarre, the cookbook grew out of Douglas's personal aphrodisiacal repertoire. In the book's preface, Douglas writes that the recipes were "collected slowly, one by one, for the private use and benefit of a small group of friends." These friends, most of whom, Douglas is sorry to say, are "older than they want to be, and all of them anxious ... to preserve for as long as may be possible the vitality of their youth and middle age," found vigor and rigor return to their loins, thanks to these dishes.

Venus in the Kitchen took Douglas twelve years to complete. Other pursuits -- collecting Persian carpets and tawny, clean-limbed boys; writing a book on Central Asian melons -- frequently impeded the manuscript's progress. But the months before Douglas's death in 1952 found him between six o'clock and dinner-time at a cafe in Capri, surrounded by loose carbon pages, half-finished aperitifs, his snuff box and an old blue beret. The charmingly chaotic scene this presented moved many of Douglas's acquaintances to offer him their help. But Douglas, his fingers cramped with rheumatism and his white hair yellowed with nicotine, insisted on compiling and proofing the book himself. It was the old roué's first project in many years, and it was to be his last.

That's not to say he didn't have any help at all. D.H. Lawrence drew the frontispiece, which made it to press despite Douglas's objections. The author disapproved of Lawrence's design. "For my own part, I must confess that this picture of a fat naked woman pushing a loaf into an oven is not at all my notion of 'Venus in the kitchen.'"

Indeed, the recipes are often as shameless as Douglas's exploits. From soups to sweets, Douglas's collection of amatory dishes ranges from the seemingly ordinary (purée of celery) to the bizarre (a stew of sparrow's brains), and derives from sources divers and arcane.

A few years after the book's publication, Douglas died, some say from a deliberate overdose. His life had been fantastically ill-spent, and his last words were no less scandalous: "Get these fucking nuns away from me." But what the writer lacked in virtue, he made up for in good cheer and intelligence. Critic John Sutherland writes that, at one time, Douglas was "regarded as one of the smartest things going" and that part of "that smartness was his keeping, for the whole of his long depraved life, one jump ahead of the law." That he did so without compunction or regret was perhaps his life's most beguiling accomplishment.