PART 1.

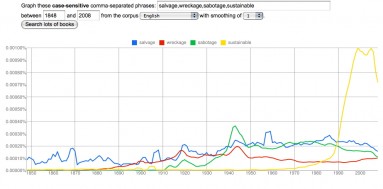

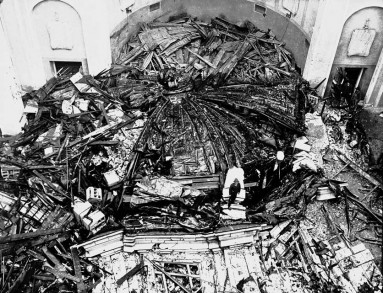

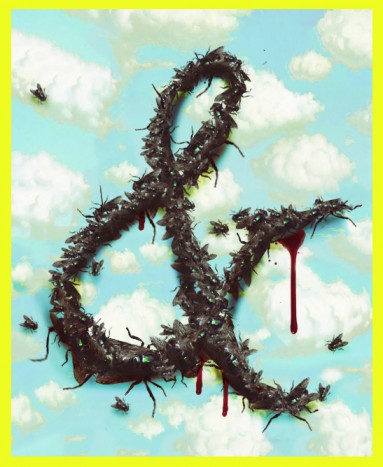

Among the manifold conspiracies that gave shape to the recent history of this species, say the last 1500 years, among the plots without which social structures would collapse in on themselves as lead-roofed cathedrals in fires and bombings do, plots such as the denial of the utter effectiveness of augury, a denial so effective that they are called mad who stand beside the river and watch sooty pigeons drop one by one by two by one into the thick-banked silt of North Greenwich, the feather splay of their kamikaze spins so obviously spelling out the very day and time when the O2 Arena will fall into itself like a cathedral or a bird or a social structure, bringing down with it tens of thousands of Michael Bublé fans, amongst all these denials and lies and foreclosures, one stands out, one doubled-back thread to be picked from the nested scrap: the history of &, the ampersand, et per se and, the 27th letter, the rag-&-bone conjunction.

The conspiracy was brilliant in its simplicity and perseverance, maintained with rare continuity from antiquity through feudalism to capitalism with hardly stitch or halt: simply to insist, ever and always, that & (the ampersand) was identical to and (the word), that the ampersand was just a conjunction made logogram in haste, a ligature’s self-knotted noose. How wrong, how utterly wrong.

But it wasn’t the ampersand itself considered dangerous, though efforts at its weaponization had been ventured, most famously by Constantinople’s advanced military calligraphers, causing Sultan Mehmed the Second’s 8-week siege in hopes of securing the technology, which took the city but not its prize, as the calligraphers set saboteur’s fire to tens of thousands of scrolls as the walls were breached, and it’s told that for an entire month the sky said, in its flaming hand, nothing more than & & & & & & & &… and there were no birds in the sky, just birds & fire, fire & fall.

No, the problem wasn’t the sign itself but what it indicated:

That is why, written in its true hand, an ampersand can be written only in flies.

***

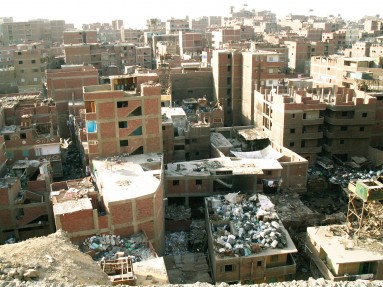

"[T]his world is a chaotic dump, above which floats, as a spirit above the waters, 'The sense of meaninglessness' ... No matter where we are, garbage always follows us. ... The theory of this world might be a theory of garbage and, as such, a discarded, heretical theory which denies fulfilment, asks not for purification and makes no demands for cleanliness that would insure survival."

Saturated with the specificity and devastation of the war and destruction of Jugoslavia, Acin’s words are also a post-canny irruption of scenery familiar since Benjamin, and indeed long before. A "piling [of] wreckage" before the feet of an anguished angel, "a pile of debris growing skyward."

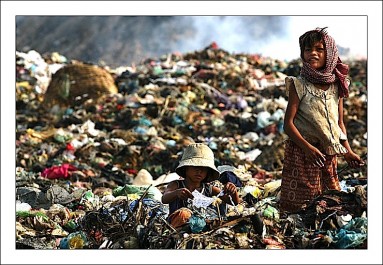

It’s old news that we live in a universe of rubbish. The fact that we scrabble psychically on an antihuman heap, a junkscape, is a truth and a trauma - and also the triumph of two ideologemes.

i) Conjoined melancholy and excitement.

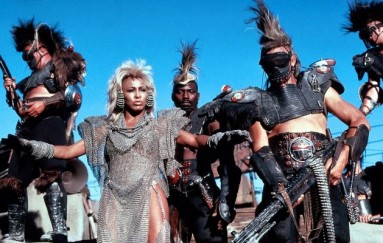

The common libidinal investment in Mad-Max dreams of rubbish-heap heroism blunts the enormity of the literal physical survival of millions on the trash heaps of capitalism, without the benefit of leather accountrements, of crossbows, of punk haircuts, of post-apocalypse and-yet chic, who struggle against rejectamental death in the slurry of garbage neoliberalism, the empire of rubbish, those poisoned on Nigeria’s Coco Beach, in Haiti by the Khian Sea, on the middens of Tonga.

ii) The tides of trash in which those of us fortunate enough not literally and bodily to struggle, but which, rather, stink up our heads in tugging dream-form, are an evasion.

There’s seventy times as much industrial as consumer waste: that it’s chocolate bar wrappers and broken lightbulbs that we envisage eating the world, rather than the opaque and incomprehensible sludge, the glimmering runoff, the contingent sculptures of refuse pig-iron and recusant minerals, is exoneration of capital. Makes the dump our misdemeanour, to be defeated with civic responsibility.

But even knowing that, we don’t pick our landscape.

Salvagepunk, a heuristic the birth and, repeatedly, end of which we’ve declared before, isn’t, of course, an answer to anything. It is an effortful effort to think a way in the scree of garbage.

This is at least the third death of Salvagepunk, and with it we notice that we’re not alone. We investigate with new attention the non-human scavengers with which we share our garbage world.

PART 2.

Amongst the various things of importance Aristotle wrote, one was this: "it makes no difference whether it is five beds that exchange for a house, or for the equivalence of 5 beds." Roughly two millennia later, Karl Marx will find this important enough to cite in the first chapter of the first volume of Das Kapital, where it appears as two equations: "5 beds = 1 house is not to be distinguished from 5 beds = so much money."

An and - not an ampersand - works at the center of this, this precursor of the value form. Because along with the contagious is worrying away at what Aristotle calls "the impossibility that such unlike things can be commensurable," there is the and of equivalence, putting not just 5 beds and 1 house together but also 5 beds and what is not different from 5 beds, and above all, those two different forms of equivalence themselves as "not to be distinguished." This is an and that neither conjoins things in their qualities nor marks them as different. It drives a separation within things (a bed and a bed as its abstract equivalent) and obliterates the differences between. So begins the paratactic grammar of capital: 1 house and 5 beds and 5 beds and 1200 dollars and 29.7 sheep and 1/52,000th of a tranched mortgage and…

And one morning we looked out over the port and realized our lives were nothing like that sky over Constantinople.

Alfred Sohn-Rethel, in his bravado attempt to link basic categories of thought to exchange itself, gives this obliteration a point of feverish vertigo: in that slimmest of moments, when, in order to be exchanged between two parties, a commodity - let’s say a bed or hours of your life or a horse or a painting - must suddenly belong to no one, not even to itself. It must become just pure exchange, without the thingness of house or horse, without even the qualification of being some one’s property, just the possibility of being equivalent in general. As for all those clinging determinations, like the particular arrangement of skin worn through on the flank of that horse or that place on the bed in the house where the sweats of your fever dried into a salt version of you, a leaked ghost to be inherited by those who bought the mattress from us for $50 as we kept our fingers crossed hoping they wouldn’t notice the second you who never rose from its sleep, or the daily destruction of the sinews in her wrist because hours is strain and repetition is fact, and all this is burnt free, the particular’s stain voided like ash.

We enact this process, on average, between 8 to 14 times every day. And even the rubbish wind isn’t nearly strong enough to huff away that gathered strata of resultant chaff, AKA the present.

***

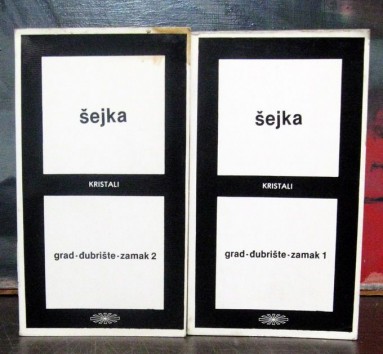

Leonid Sejka knows the world is an endless junkyard.

At its centre lurks the limit of his artist’s brush, an unpaintable, unthinkable mechanised zero point, a garbage grinder devouring all forms in the labyrinth.

The truth is more awful and more banal. There are machine in the junk yard - more than one - but they don’t destroy, they birth garbage. The world is the grounds between engines spinning trash from matter. What then later reconfigures that rubbish into fecund paste isn’t machine but animal. Like Cairene pigs, abjured porcine uncanny.

Humans are anti-rubbish. This isn’t a value judgement, not an aspiration nor a Promethean swagger. It’s a fact spoken with a shrug, a side effect of anthropocentrism, and a due respect to rubbish itself. Humans are wholly unconvincing as garbage.

"You never knew what you would find in that rubbish dump." Dambudzo Marechera on life as a black child in the discards of empire, in white supremacist Rhodesia. "Broken toys. Half-eaten sandwiches. Comics, magazines, books. One brilliant blue morning I found what I thought was a rather large doll but on touching it discovered it was a half-caste baby, dead, rotting." This isn’t evidence of the rejectamentalism of the human but, in the shock the find occasions, of its opposite. Even a corpse is never rubbish: it is always the dead. A cold, quiet human agent. "I fled as fast as I could," Marechera says of the heap, "back to the safety and razorfights of the ghetto."

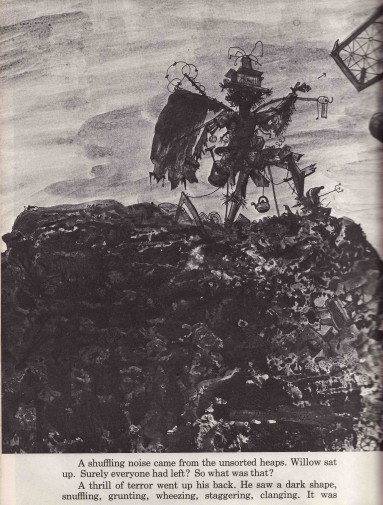

The child and the corpse are gathered. And opposite them, at the antipode of the human alive or dead, trash itself walks, all across culture, enmonstered.

This is the telos of rubbish, a chest-hollowing weird trash sublime. But these monsters are no more Garbage Virgils to our Trash-Inferno-trapped Dantes than the dead can be. The dead are not of the rubbish, so can’t guide us either in it or to its heart. The monsters, by contrast, are the rubbish itself. "Nothing could be understood from this jumble of misshapen forms," says Muriel Grey of her rubbish monster in The Ancient, "while all around him, the rest of the world was explaining itself." All these patchwork refuse horrors’ agendas awe, but are opaque.

The human; the monster. Neither helps. We need recourse to a mediating animal point between. Mindful that it’s less than they deserve, all we can do is petition, implore, entreat the beasts to do as we’ve had them do in all our endless banalising stories: to pretend to totemhood, to walk with us. We need an animal copula, a conjunction to attach us-ness to the rubbishness in which we’re lost.

The pig is the maw, event horizon, Schwarzchild radius, too voracious to conceptually accompany, too easily parodic, too unsettlingly us-like to trust. The junkyard dog too freed by ferality. The pigeon too dumb. The cockroach too encoded as abject for us to follow.

The worm, that garbage grinder that Mary Butts calls "a red tube for the excretion of earth," is a candidate, and as an agent of decay it might seem perfect in an excremental world. Consider this from Nathaniel Cobb, in the Yearbook of the US Department of Agriculture, 1914:

If all matter in the universe except the nematodes were swept away our world would still be dimly recognizable, and if, as disembodied spirits, we could then investigate it, we should find its mountains, hills, vales, rivers, lakes and oceans represented by a thin film of nematodes.

The problem, though, is that the honorable philosophy of Vermiformalism is, like the rot that is its grundnorm, both post- and pre-garbage. It is totalised mulch, rather than, as rubbish is, collective, inhumanly democratic.

Not the worm, then. We need another beast vector of trash philosophy. One looping, urgent, iridescent and vile, both beautiful and ugly, irreducible to and inextricable from rubbish qua rubbish. Dead-again salvagepunks pick our way not out of but endlessly through the trash following the fly.

PART 3.

But materials persist longer than the span in which they can be made the nothing of exchange.

Sure, doggy doesn’t understand abstract equivalence, even if patience has been bred and beaten into him. But at the end of that understanding is a material memory, carried in the triangulating link of property that spans between coinage & meat but can’t erase the thick specificity of these coins, that meat. That memory hides itself in the daylight of our transactions, the scent picked up dogs who "don’t get it."

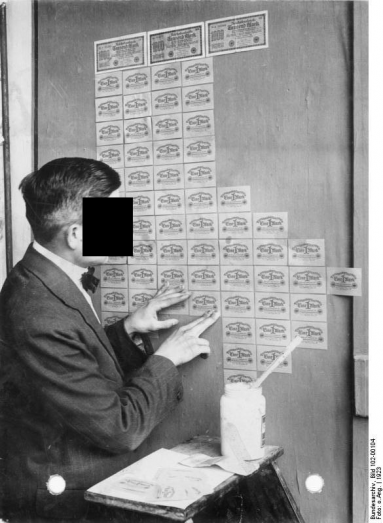

The bonds between meat & coin, which must be written with ampersand, can only be seen when the value between the two breaks down, becomes unmistakeable in its stasis. Like in Vienna, in the period of early 20's hyperinflation when useless Deutchmarks were burnt for petty heat or used to paper pretty the walls, and Anna Eisenmerger, whose banker told her "My dear lady, where is the State which guaranteed these securities to you? It is dead," watched as, "Mounted policemen were torn from their horses, which were slaughtered in the Ringstrasse and the warm bleeding flesh dragged away by the crowd..." The palace of culture is built with dog shit, Brecht said, but as for what is built with horse meat and heated with the fires of Deutchmarks, we simply cannot say.

Or nine decades later, a year a half ago in Essex, where a woman was arrested for "stealing" spoiling food, including meat, thrown out by Tesco after a power outage. Tesco claimed that the contents of the bin still belonged to them despite it being discarded and rotting, and therefore that bonds of property exceed the collapsing protein weave of sarcomere as the flies get down to business. And Tesco also proudly state that in their commitment to sustainability, they send thousands of pounds of leftover meat to be burned for electricity every year. I can’t help but think that if they only ever burned the meat from the start, using it to power the refrigeration to keep fresh the fuel that will not be wasted on human hunger, things would be simpler. But no, there’s still the and that weighs, evaluates: flesh in the rubbish bin and flesh in the incinerator and flesh in the package, bathed in electric light, and flesh in the belly and flesh in the jail and flesh in the street, torn from and along with its horses, their steam rising up like gutted recollections.

But three years ago, in Egypt, the outbreak of swine flu in Mexico led to the fear that Egyptian pigs could become sick. As throughout porcine history, this doesn’t mean calling a pig doctor. It means culling: the immediate slaughter of all 300,000 plus pigs in the country. Amongst those massacred and uneaten were the pigs of Manshiyat naser, the "Garbage city" on the outskirts of Cairo, tended by the Zabbaleen, the Coptic Christian garbage collectors the city can’t run without. The destruction of the pigs destroyed the livelihoods of thousands of Zabbaleen and their families. In anger, one of them said, "Let Cairo drown in garbage." And it did, & the flies came & so too the smell that ensued, AKA memory.

***

Insect-fouled narration. A flecking of salvagepunk.

Touch connects. With an exchange of atoms we’re attached to something by something. The light but unendurably annoying repetitive haptic bother of a fly’s feet is a linking, let alone the vomit-glue of that grotesque pad tongue touching down on us, and off again, on us and off again, repeatedly, one stop en route to the garbage.

To eat the garbage and puke it up, to puke bits of us on the garbage and suck it up again, to puke it back down on us in a noisome gloop in which we are conjoined with the trash in which we live.

Like Beelzebub-led angels on their way down, flies blunder into trouble but can still fly. They don’t, or even worse, do, watch where they’re going. In turd footprints, drool and their own spoor, they trail a braille of shit. A resistant and tantalising code.

The fear is that it says they’ve already made it to the bottom. That Hell has a long been a hole for landfill, that we walk on striae of discards deep within the pit. That there’s nowhere else to go, not even anywhere worse.

Now, "This is Hell" is an antique reveal. That it’s cold and packed full of our crap is a slightly newer insinuation, a sutured despair-cum-hope-cum-despair-cum-hope-, and so, fly-foot, on.

That fury we feel at the repeated interventions of any fly is massively disproportionate to the lightness of its touch. What drives it is anxiety. We feel ourselves the objects of attention. We’re noticed by the universe, via order Diptera.

Three lifecycle ways in which fly can guide in the rubbish heap.

i) Through the words it writes as neonates, on rust, on some fender, on flat rubbish, on the trash-strewn ground of the dump. It can write them in the ooze of its maggot bodies.

ii) In relentless veering in its majority, in a swarm, a cloud not of unknowing but of insect knowing. Fervent smoke.

iii) Scattered breadcrumb-style in death, laying a path in its little raisin bodies, from point to rubbish point.

We’re not obliged to do anything about any of this: it just is. No one said this revelation was invigorating, or that fly was a salubrious animal companion. "What’s that, Buzzy? Timmy’s fallen into Hell?"

The Dipteric is no dialectic. It’s not a sublation; it’s a shitpad joining of incommensurables at the end of fly’s legs.

Against this scandal, there are two obvious defences. One is the strategy of Renfield, Dracula’s fly-eating slave:

My homicidal maniac is of a peculiar kind. I shall have to invent a new classification for him, and call him a zoophagous (life-eating) maniac. What he desires is to absorb as many lives as he can, and he has laid himself out to achieve it in a cumulative way. He gave many flies to one spider and many spiders to one bird, and then wanted a cat to eat the many birds. What would have been his later steps?"

Like the protagonist of Alain Mabanckou’s African Psycho, an inadequate serial killer hemmed in by junk, Renfield is a pitiful wannabee monstrosity. His mania is a function of the world, not of Nosferatu.

Renfield has a fool’s Capitalism envy, tries to imitate its voracity with cringe-making misprisions. He thinks the accumulation ends in digestion, a hoarding in the body! That it is, if in predatory fashion, about sustenance, rather than a drably murderous monetised dynamic of itself.

And all the animals he hopes to ingest are multiples of smaller animals he has fed them, down to, and ending at, the fly. Fly, in his idiot belly, is the indivisible atom of animal, limit point.

But no stomach acid can dissolve the Dipteric. It mediates organic and rejectamental. This doomed madman strategy is to try to reduce the fly to the merely former.

The bureaucrat, the asylum’s director, tries the opposite tack. To make-garbage the fly.

This, supposedly, is the purpose of flypaper.

To snare the fly, kill it, to throw it away as rubbish.

But this is no more convincing than Renfield. Flypaper is a commodity far too unlikely, too lunaticly engineered, too baroque and rococoly symbolically freighted to have been thrown up by the exigencies of commodification, for all its demented invention.

A tightly wound spool of paper coated in sweet viscous poison, uncoiled like a streamer at a fetid antiwedding, trembling with hungry struggling flies, their terrible whispering feet silenced, anchored in glue, there to die and loll and rustle with breezes, macabre chitinous decor. A display of corpses in spiral vortex, a strip of wallpaper without a wall, turning like an insectile drill.

There is no fucking way flypaper was not designed by a semiotician.

And by one who, whatever the brief, knew that flies could never not be vectors. Throw that long heavy ribbon out, all specked with fly dead, it will land on the trashheap in the shape it’s eager to take, overlooping and sticking to itself, coiled over its own length. Insect typography. Compulsively conjoining. Salvaging a punk meaning for itself from its animal garbage self.

A fly ampersand.

[image by Armando Veve]

[image by Armando Veve]

PART 4.

The story of those pigs in Cairo is a story in the uneven history of salvage, in its underside, which we call salvagepunk. We add that suffix because salvage alone, born of and in the panic of value, of weighing the saving of worth before or during or after a catastrophe, is torn between and and ampersand.

In the 17th century, salvage meant a payment: the remuneration given to sailors for saving another ship from going down, the equivalent to the cost of a portion of the cargo that would have sank. This is the same period when, in the Mediterranean world, it became newly possible to continue shipping in the dangerous waters of winter. But not primarily because of new boats. Because of insurance, which drives a separation within disasters themselves, between profit lost and commodities – such as human labor - lost, such that it becomes profitable to ship unabated in full knowledge that ships will be saved only on the books, while their hulls gape like grottoes under the chop.

In the 19th century, salvage meant a saving, rescuing property before it was lost, with the “salvage corps” of firefighters in Glasgow, London, and Liverpool, extra-municipal organizations that ensured buildings to be insured were up to snuff and which, provided you could pay, would snuff out the fires or root around through the charred remains for something to be dusted off and sold again.

In the 20th century, salvage meant the recuperation of what was already lost, combing the fields of wreckage. Fittingly, it’s the first World War, that apogee of waste that provided capital with the ground clearing it needed, that enacted the shift: the British Salvage Corps, who picked through the dead, took their shirts off their backs, made them into gas masks, so that the living did not breathe in their death but the death of another gone not wholly to waste.

In the 21st century, the history of salvage’s meaning curls back on itself as if ampersand, the split becomes absolute: on one side, hands pour acid over motherboards to strip out their last heavy metals, hands put acetylene fire to the tremendous hulls of decommissioned tankers. On the other, central banks dream that bailing out a sinking financial ship by flooding it with liquidity will garner the biggest salvage payment of all: the continued pseudo-health of capital.

The two are bridged by an ultimate denial of history: the fantasy of sustainability, of salvage without the disaster, in which consumption and preservation stand magically hand-in-hand, peering like the blind into the smog.

***

And she is going as fast as she can but the rope around her waist frays and snaps, and her ruined trousers head abruptly south so she is shuffling from tor to rubbish tor hopping and holding up her own clothes and she looks nothing like a free-runner. She trips and comes down hard on her right thigh on the corner edge of what was once a dishwasher or a small fridge, protruding from the rubble of grey refuse like robot bones. She rolls. She slides painfully down the hillocks of trash, clamping her hands to her mouth to stop from shouting, hunted as she is by mutants (insofar as they can run through their own cancerous pains); or blank-masked enforcers from some presumed authority somewhere (though she has eavesdropped on them sobbing at night into dead radios, smelt their uniforms and seen their patchwork repairs); or marauders running as fast as they can (not fast) over the garbage dunes, holding reclaimed steering wheels in front of them and blowing Vruuumm Vrummm! noises as they come. In any case someone is coming after her.

She comes to a rest in shadow. Above her is an overhang of chickenwire and tins. She freezes. Above her is a terrible shape, a jagged many-limbed thing, a tree tangled from the composites of aerials and tv innards, plastic extrusions like growths in its multipart trunk, thorns of glass and shattered plates. Its branches splay - finger after finger of tubing, and intricate wicked ribbing. Dangling from them like dirty dank foliage, like the skins of victims, are dish clothes, and umbrellas’ countless ripped canopies. Nylon in dinged colours.

She cannot believe it. This is the place for which she’s been looking, of which everyone in the dump whispers. The parentload of violence, growing on weapons, or budding them, its roots reversing peristalsis.

She begins to dig. She does not hesitate, despite the dangers of which she’s been told. She excavates with a flange of wood, with a broken saucepan, with her hands. She digs through layers of rubbish. She digs archaeology. She goes down much faster than she should be able to, through centuries of rubbish. Discoloured and granular, but plastic, resistant to true rot. Specific. Resilient. She is soon in a hole in the rubbish, that rubbish in a much much bigger hole.

She is digging for a weapon, and she finds it. Puts her hand at very last in the growing dark on a still-dense cardboard tube and halloos and hauls and up from the earth flexes a long stinking insecty strand. She twirls it around her head. She snaps it, whoops and waves, dislodging a few flecks of adhesive but not one of the tiny bodies.

She turns to face whatever is coming, brings her fly-whip down.

PART 5.

Salvagepunk has been around for a while, even if it didn’t get its name until about 3 years ago. It is the other side of salvage, the ampersand side, when the properties of things become a sabotage of their purpose, unbound from their identity as if by flies, bound together with other broken things, as if by flies.

Et per se and. Which means: And in itself and. The in itself of something becomes hooked, the conjunctive barbs on each side. Kurt Schwitters thinks it precisely with the word: Merz, which is kommerz, commerce, from which the with has been severed. Deep within enemy territory, commerce is ruined and, as Schwitters says, one learns to scream with household refuse.

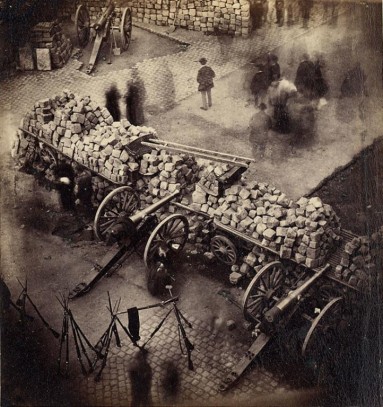

The operation of salvagepunk starts when the being wasted of materials is the occasion for them to become war on what brought them to be, in favor of those who use them, against those who owned them. The form of it is that of the barricade#: the use of the city against the city in the name of the city. The use of the materials of the city, against the designated function and flow of the city, in the name of what the city has already been beyond that function.

The ampersand therefore does not mean and. That has been the tremendous lie. It means and/or: the conjunction that joins what should be mutually exclusive, the incommensurate, not flattened into value, but undone into jagged proximity.

We tore the locks from the building and wound through them the copper wire borrowed like veins from the walls. To these we added the doors, for which there was no longer much need. To this we added what remained of the building. Then we got to work.

I could speak this again in rust and hotwiring, in bicycles made of bombs or vice versa, I could speak of The Bed Sitting Room or Hyesoon or Schulz or Hrabal or Mad Max or Berg, but I won’t because two years ago I wrote to you, I was in a terrible cafe in a terrible town in California & I wrote to you to say listen, there are two separate things, in Greece, there’s a town called Keratea in southeastern Attica, it has 16,000 people, it is 40 km from Athens & they tried to build a landfill there to swallow all the trash from the city & the people there refused it & on the road that skips the town but links the capitol to the dump next to the town the people of Keratea burned the construction vehicles & set up road blocks & dug a grave-deep trench like it was a war because it was & at night they shone lasers into the eyes of the cops & firebombed their houses because it was war & one man said at age 60 I finally learn how to make Molotovs & on the walls there were children’s drawings of riots, it was of these I wrote to you, these drawings we could not find online but beside me in the cafe was the other thing, two terrible people who were chatting, all yoga pants and popped collar & I noticed the color of nail polish & this neon glare must have been one of the colors in those drawings, a stray crayon or laser or shard flung far west & I wrote you to say how is it that the same color is both & to say that maybe it is in writing that we affix the glue to which trash sticks like glitter, but we both know that’s only when that glue is heated by the steam that rises from all the bodies together & many dumpsters dragged into the streets & set ablaze like trash in Naples where a young Sohn-Rethel wrote “that which is intact, that which just works, arouses misgivings and doubts, because the fact that it just works means that it can never be known how and for what it will work” & one morning outside the EU convention there was a horse left by the people of Keratea & it looked like total crap, cobbled together with scrappy wood and chunks of highway, and an idiot’s grin and a sign around the neck that said SORRY & the politicians having heard what happened in Troy thought themselves so clever & dragged it inside their gates & took axes to it to kill the invaders & they hacked & blood flowed & they hacked and realized there was no one inside, just blood & blood & they took it to pieces & that night their bodies, coated with blood, stiffened like driftwood in their beds until they like horses & cathedrals could not move & having written you this I stepped outside in that dismal town & looking up I saw the sky was so full of flies that you could not start and/or put out a fire