[Regarding the traversal of this nation from coast to coast with one's father, in the key of Laurence Sterne's A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy, albeit in a USA falling apart at the seams where economy, time, gender, and space join. In the previous entry, we learn that: a) the narrator - an unemployed house-painter/optician with a stubborn commitment to landscape omens and a severe distaste for Christians - has something rattling in his chest that is not a cough and b) America's elderly population has fled the cities en masse to stalk the fringes of the highways, where they hunt by scent alone those who do not move with adequate haste.]

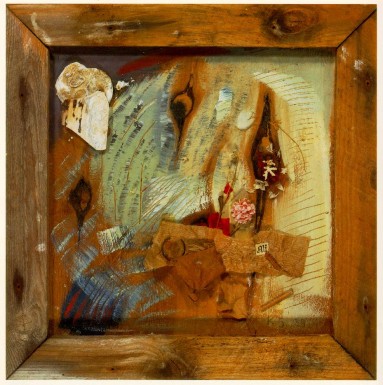

Corresponding images:

&

&

‡

Nearly all - say 17/20ths or so - of the motels in The Hinterland had been closed at one point or another, but only a good two-thirds of them stayed that way. The rest reopened, though that isn’t quite the right verb. Better to say: they persisted, yes, they persisted in a shade of their former selves, partially functional. Neither with nor without vacancies. Merely leaking slow, chunks torn free yet lumbering ahead as severely wounded bears do when they drag themselves red and partial from the river, gashes the size of foxes across their neck and middle.

For the most part, they bore the expected traces. Sheets from which stains couldn’t be coaxed to leave. Scorch marks on the ceiling. Copper wires dragged from the walls like borrowed veins. Viscous bathtubs full of that unmistakeable substance. A surfeit of rats. The start of unfinished epic poems concerning the present situation, and its origins in the deafening plop of the third housing bubble, carved deep into the wallpaper of the Oak River Conference Room. Its finish - concerning the reinvigoration of the corn market after desertification took Kansas by dust storm - in the Maple Glen Lounge, where there was, perhaps coincidentally, not a stitch of wallpaper. The middle cantos nowhere to be read. Spotty Wi-Fi. Persons whose relation to each other could be called neither friendly nor hostile all sharing a bridal suite yet still vigorously refusing to break out the mini bar.

But some more unusual occurrences could be glimpsed too. A dearth of rats. Smiling receptionists, though usually missing at least three fingers, always missing at least two. A breakfast buffet with decent scrambled eggs. Ice machines that had, at some point, been emptied of water, refilled with old bile. Still functional and very exhaustively cleaned, but that taste just never quite leaves. Always a whisper of acrimony left behind, still sharp enough to ruin even an assertive glass of scotch or ketamine or even fresher bile. A closet full, seriously fucking full, of fingers.

Three-quarters, my father said.

What, I asked.

It was at least three-quarters of them that remained closed, he said, his eyes near closed as though tabulating the sum behind their fleshed half-light.

Don’t be ridiculous, I snapped. There’s no way it was more than two-thirds. Especially if we are defining “not closed” in terms so markedly expansive as I’ve outlined. I simply mean those where people came to sleep again, where they came to eat or hump or both. (I raised my eyebrows for emphasis. He wasn’t watching.) You’re just getting bored from the drive. Getting testy. I’ll take over next stop.

I will never know where you get these ideas, he muttered with a certain sadness. Obviously not from me, I’ll tell you that much. Fractions aren’t something to be to be taken so lightly. No, he said more deliberately now, they’re nothing to be trifled with, the right hand testing the length of his mustache, which was the same as always, the precise length that could be reached by the meeting point of teeth.

Neither are foxes, I said, neither are foxes.

Even in times such as these - unabated he went on, choosing to ignore my comment and avoid thinking of foxes, in fact, he was not to mention them or acknowledge any mention of them or their certain existence for the duration of the trip, with a single exception toward the Further West and that was actually a coyote, as he knew all too well, despite what he would say in half-assed protest - there’s no excuse to believe that things are just whole or not at all, with maybe the sharp-eyed sighting of a rare half from time to time…

I never said that, I interrupted, you know I never said that.

… No, he went on, once more acting as though my comment hadn’t been audible, the eyes once again a mustache-hair width from closed, those lids worrying away at the slit of space between, no, there’s been such an awful blooming of partials in this last decade. But don’t go thinking that means that they are just wholes that got themselves damaged or reduced. Don’t think there are any fewer - not less, fewer - healthy wholes out there, roaming the wide earth, rutting and hunting, standing still in earthquakes, fitting within the confines of thought, just like they always have and will.

I won’t, I said. Don’t worry about that.

Well, good, we’re finally getting somewhere, he said quickly and flashed a smile. Outside the leaves were aflame. In sympathy with the season, the color was up in his cheeks. This was, after all, one of his preferred topics. No, don’t think that the partials used to be wholes. And don’t make the other common, but equally deadly, mistake. You know what that is?

I was silent, feigned interest in the leaves slurring by outside, although of course I knew.

Come on, you know. I’ve told you often enough. (It never failed to surprise me just how much he was aware of having repeated himself and how he took that with real pride, as evidence of his rhetorical clarity, because, as he liked to say that a famous Polish rhetorician once said before he too was swallowed into the camps never to be seen again in either pages of scholarly footnotes or winter streets, “An argument, like a house of glass, needs a good clear foundation.”) Don’t assume they were nothings that merely got stuck part of the way way to toward full whole-ness. You see, a partial…

… is complete in its partiality, I finished his words. It is the integral expression of an unfinished thought, cursed into material existence by an accident of abstraction, hereafter unable to become either whole or nothing. Outside I saw what could have been a stripped warehouse, but I was too distracted to be sure and the difference between a merely empty and a truly stripped warehouse is immensely subtle, too subtle for all this talk of abstraction and rutting.

That’s right, he said, nodding, teeth searching for an unclaimed hair, that’s just it. He kept nodding, rehearsing the rest of the logical deduction of partiality in his head, silent, but with small nods to keep the logic’s eurythmic beat. You know - he said, the nod suddenly stopping - we’re coming into their part of The Hinterland. The partial’s part. Full of the 2/9th motels and all their vicious jags, their abutments, and untiled pools.

Of which only two-thirds ever remained fully closed…

He let it slide. That’s why we have to keep persisting, he went on. Keep whole, carry that flame ahead like a flag. A standard. Yes. That. A good solid measure of whole. Barrel-chested wholeness, the kind you could set a candle on without fear. The fiber and white blood count kind. Not to become 12/47th men or whatever the current percentage on the roads is supposed to be.

I thought we were supposed to be precise, I chided. Outside, behind a glass-topped wall, the suburbs had broken down, blubbering in space and yard, weeping with siding and insulation. Pseudo-gutters everywhere. A readymade dog house self-fisted into incongruity. No, I recalled to myself, not broken down. The partials, the partials. Besides, these suburbs couldn’t be more than five days old. The roof membrane still suspect to suggestion or fists.

There’s a time for precision, he went on. And there’s a time to stay whole. Sometimes they aren’t the same time. Just remember this: it’s subtracting from another whole that will doom you. You could never be partial, because you weren’t that from the get-go. You know that. But you could become less. So know that. Unwhole. Do you know? (He didn’t wait.) Taking a part of something else that deserves to be whole or to be allowed the chance to fall away into nothing, to take that part like it was an entire partial, I mean, hell, partials, do what you want with them, they flit anyway, go ahead and stitch them together, use them as a jack to change a tire, whatever, make a demi-scarf, fist them like hollow doghouses. But to subtract something from a whole and add it to yourself… No, that’s what we can never allow. He had the gun out yet again, for good easure, as he always did when we hit this topic, and on every point of emphasis, it swung just a touch too far in its expressive arcs and scraped lightly on the glass. Because that’s what separates us…

Yes, I said. The subtraction. That.

‡