(via Kumi Yamashita)

If our identities are only self-conscious creations, where does that leave us? Where does that leave love?

In Baldassare Castiglione’s Book of the Courtier, an influential Renaissance-era attempt to define the perfect gentleman through a series of dialogues, one of the aristocratic speakers offers this advice for a courtier in love: “When the courtier wishes to declare his love he should do so by his actions rather than by speech, for a man’s feelings are sometimes more clearly revealed by a sigh, a gesture of respect or a certain shyness than by volumes of words.” Words are too easily employed by “cunning” men who are skilled in the art of contriving “false demonstrations of love” — men who seem “quite ready to cry when they really want to burst out laughing.” The lover should instead “use his eyes to carry faithfully the message written in his heart, because they communicate hidden feelings more effectively than anything else, including the tongue and the written word.”

But this distinction between words and actions is troublesome. In order to know he is in love — true love, the kind figured as a sort of divine visitation rather than a convenient decision on the lover’s part — the prospective lover must understand the “message written in his heart” as genuine, uncontrived, spontaneous feeling. But then he must articulate that message with his eyes, transforming the authentic awkwardness that first made him aware of his love into a signifying pretense. That which is supposed to make a lover know his love is sincere is subsequently made to serve as a dubious performance of sincerity. The lover must govern the representation of feelings that, if sincere, would be beyond governance, and at the same time, he must also recognize sincerity in feelings he know can be contrived and deployed strategically. How then can he ever know whether his feelings really are sincere if he must always stage-manage their expression?

This is the sort of annihilating reflexivity that, according to sociologist Anthony Giddens, is one of the defining characteristics of modernity. In Giddens’s view, tenacious self-consciousness stems from our having been uprooted from local conditions and circumstances that once stabilized identity. The sorts of cosmopolitan problems once reserved for Renaissance aristocrats now afflict nearly all of us. Like Castiglione’s courtiers, we are obliged to imagine that we can perfect ourselves in accordance with a social ideal generated in the abstract.

In a sense, the Renaissance court may have functioned as an early example of a nonplace, Marc Augé’s term for those artificial social environments that deny the contingencies of nature. These could be understood as spaces in which our identity is entirely determined by abstract social relations — where identity becomes, in effect, entirely political. In contemporary urban life, we pass seamlessly through such spaces, our identity is no longer fixed by a set of local traditions. Instead our local practices are linked to globalized social relations through widely disseminated discourses and procedures, through generalized nonplaces and brands. We use ATMs; we eat at McDonald’s; we shop at supermarkets and H&M — the stores are more comforting and familiar than the people around us, who more often than not are indifferent strangers who signal their benevolence by studiously ignoring us.

We no longer count on a community to provide the context in which we can be recognized; we can be anywhere and continue to act like ourselves. Whereas the horizons of local familiarity once limited what we could imagine for ourselves, modern life has situated us in broader “abstract systems” — standardized ways of doing things and ubiquitous cultural reference points, universally recognized procedures and authorities. Tradition — “how things are done here” — has been fatally disrupted. We can enter an elevator in any city or an Italian restaurant in any American town and understand what to expect and what to do. And thanks to the universality of money and the pervasive norms of capitalist market exchange, we trust we don’t need a personal relationship with a pub owner to get a pint.

Individuals are free to ascribe personal reasons for routines that were once “simply what is done.” We come to believe that we can control who we are to a far greater extent, so we try to master the social processes that shape us, dictating their outcome by administering carefully what we feed into them. Modern identity, then, is born of the alienation of auto-surveillance, which makes the self seem a discrete thing we manipulate from behind the curtain of publicity. But this only serves to accelerate those processes and make them more unpredictable. “The point is not that there is no stable social world to know,” Giddens claims, “but that knowledge of that world contributes to its unstable or mutable character.” By wanting to know about social processes, we set in motion the means by which they mutate incomprehensibly. Reflexivity generates stultifying angst even as it makes self-cultivation possible.

In “The Metropolis and Mental Life,” sociologist Georg Simmel claims that the complexity of modern city life brings about a rise in time-consciousness and the death of spontaneity. “Punctuality, calculability and exactness” lead to “the exclusion of those irrational, instinctive, sovereign human traits and impulses which originally seek to determine the form of life from within” — like the sort of sincere love that can be a “message written on the heart.” You would think the advent of mobile phones would reverse this, affording us the freedom to live more provisionally and seize upon the random opportunities city life can spontaneously supply. But such spontaneity runs counter to the deep emotionality Simmel associates with the premodern, “organic” way of life, with its slow pace and its strong, irrevocable ties. Spontaneity in that world was an unstudied responsiveness, the ability to fully inhabit one’s emotional responses within the relative security of small, sheltered world. Now the urban blasé attitude characterizes spontaneity in the form of “keeping options open.”

Is it possible to monitor and deploy one’s feelings and still actually feel them? This brings us back to Castiglione’s courtiers and their love problems. Considering the precariousness of courtiers’ status at court, dependent as it was on the ebb and flow of personal relationships and access to superiors, and the degree to which the negotiation of those relations relied on deliberate self-presentation as a mode of diplomacy, we might regard them as our psychosocial forebearers. Their work was also their leisure, as ours is becoming, and their uncertain place in the social hierarchy means they knew no “ontological security” — that is, as Giddens defines it, “the confidence most human beings have in the continuity of their self-identity and in the constancy of the surrounding social and material environments of action.”

For Castiglione, self-monitoring is not a problem at all but rather a ramification of that elusive ideal quality of sprezzatura, the “certain nonchalance which conceals all artistry,” which is supposed to be the surest mark of a true gentleman, the essence of the courtier’s social capital. Underlying sprezzatura is the idea that the value of an action is in how it is received rather than in any essential quality of the action itself. Deeds themselves become arbitrary, which in The Book of the Courtier leads to the ludicrous equivalence of disparate practices: for instance, how one appears on the battlefield and how one appears at a masked ball are judged by the same criteria, which have nothing to do with why one fights or why one dances. They are merely occasions for sprezzatura. How the courtier appears when in love, too, is evaluated according to criteria that abrogates the emotions presumably involved. Castiglione’s description of the ideal courtier in love renders the actual feelings of love superfluous.

Those actual feelings are precisely those awkward sorts of emotions that the doctrine of sprezzatura intends to suppress. Because feelings are arbitrary within the sprezzatura system, whether one genuinely loves is irrelevant, as insignificant as the reasons one goes to the masked ball. One simply goes because one’s presence is required. One loves because a gentleman wouldn’t be complete without it. In the ideal universe of perfect sprezzatura, men and women apparently interact with one another without requiring any understanding of why.

But supplanting love with sprezzatura, making a virtue of a courtier’s vigilant reflexivity, seems to spite the otherwise governing definition of love as beyond personal will and control. Implicit in that ideal of love as an uncontrollable force rather than a choice is a yearning for a social experience beyond strategy. Such a love could serve as an ontological anchor, providing a basis by which they could know who they “really” were in the midst of all the calculated self-presentation.

In modernity, we have come to rely on similar hopes for our own ontological security. To ease the anxieties of self-consciousness, Giddens argues in The Consequences of Modernity that the open-ended nature of modern identity means we have a constant need to have trust refreshed. We get some of this from the continuity of the social world — the familiarity of the buyosphere from one town to the next. But ultimately this is unsatisfactory:

The routines which are integrated with abstract systems are central to ontological security in conditions of modernity. Yet this situation also creates novel forms of psychological vulnerability, and trust in abstract systems is not psychologically rewarding in the way in which trust in persons is.

We need to draw basic trust from reciprocal friendship, yet the ground for such relationships continues to be eroded by modernity’s technological advances, which systematize friendship into social networks for our convenience. Companies like Facebook promise us the ability to manage the intimacy and intensity of our ability to love, but the ability to manage it renders it suspect.

Thus an intimacy deficit widens, and we expect more of personal relationships in order to close the gap without knowing how to get it.

Most of the speakers in The Book of the Courtier seem to experience this deficit, too, and yearn for the joys of certainty that they are loved. One explains that “no other satisfaction” equals that of knowing his lady “returned [his] love from her heart and had given … her soul.” Another agrees that “the greatest happiness” is to share “a single will” with his beloved. The Magnifico asserts that “the feeling that one is loved himself” is that which most “stirs” the heart. Such hopes would seem to betray a deep-seated uneasiness with the deception that sprezzatura requires, revealing a wish for a relationship that would be a haven from perpetual contrivances.

But since the postures of love are more valuable as an appurtenance for courtiers rather than an essential truth, mutual love becomes impossible, and mutual suspicion inevitable. Not surprisingly, then, love must be defined away from the mutuality that Castiglione’s players seem to long for. The Book of the Courtierconcludes with a rhapsodic account of ideal neo-Platonic love, that proposes to make sincere communication between lovers unnecessary, rendering the beloved’s actions as irrelevant as sprezzatura renders the courtier’s. Love, as described in these concluding passages, is “a certain longing to possess beauty” rather than something experienced with another person. A lover must remember that “the body is something altogether distinct from beauty,” and though an individual may be beautiful, that individual’s behavior has nothing to do with it. So when an attractive woman grants her lover a kiss, the lover finds it pleasurable not because it reveals shared desire but because the lover’s “soul” is thereby “transported by divine love to the contemplation of celestial beauty.” The soul “turns to contemplate its own substance” and “perceives in itself a ray of that light which is the true image of the angelic beauty that has been transmitted to it.” The beloved becomes a mere springboard for the lover’s contemplation of the divine in himself.

That kind of love doubles down on reflexivity and self-consciousness rather than absolving it. In contemporary times, we may have devised a similarly solipsistic solution to our conundrums of love and insecurity: smart phones and social media, which let us live in constant communication with our networks on our terms while preserving our own kind of sprezzatura, the noncommittal openness, flexibility and responsiveness to rapidly changing circumstances, which also happen to be qualities highly desired by employers.

Shared experience is no longer local phenomenon but something that happens in virtual communities, where identity is a perpetual work in progress, a striving to reach a home that is not a particular place but a state of mind, a realization of some ideal community that nurtures an ideal self. But it may be an unrealizable fiction.

Our genuine individual idiosyncrasies — the sorts of things that might have allowed the kind of mutual love that cherishes the uniqueness of the particular individuals involved to flower — are replaced with efforts at coming up with contrived ones. Because modern city life is so impersonal and objective, Simmel claims, individuals try extra hard to be unique in whatever ways remain open and haven’t been legislated or subordinated to economic efficiency. “Extremities and peculiarities and individualizations must be produced and they must be over-exaggerated merely to be brought into the awareness even of the individual himself.” The internet is an extension of the metropolis as Simmel saw it. It has made that condition more acute, automating stimulation, bringing ever more content before our eyes, giving us an endless stream of novelty and taxing the limits of our attention span.

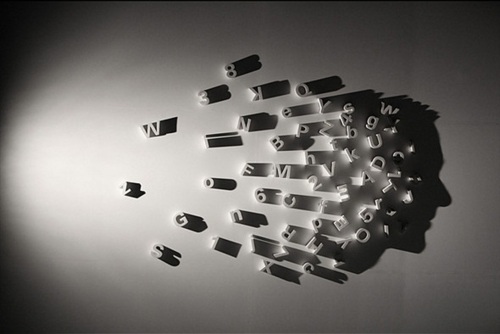

Social media becomes the site where autonomy struggles with anonymity, where social recognition struggles to remain uncommodifed. The Internet Metropolis strips away opportunities for individuation and gives us commodities and geegaws and such to compensate for it, keep us distracted. It prompts us to package ourselves in an effort to stand out amid the chaos, even to ourselves, so that we ourselves can recognize ourselves as even having a identity. Renaissancesprezzatura let courtiers in a highly competitive hothouse environment interact with one another with benign deference, as though it were a hermetic realm of polite decorum. Our mediated version in social networks lets us play potlatch while we build our brands in plain sight.