"Photographs, which cannot themselves explain anything, are inexhaustible invitations to deduction, speculation and fantasy." --Susan Sontag, On Photography, 1977

"It is necessary that the piece of card is animated with some help from me, giving it meaning it did not yet have. If I see Pierre in the photo, it is because I put him there." --Jean-Paul Sartre, The Imaginary, 1940

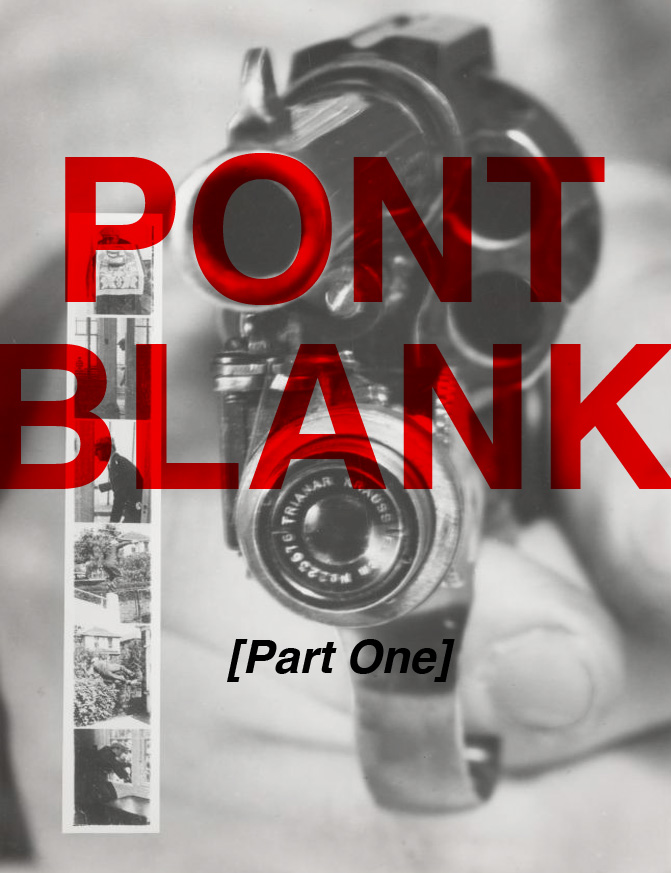

This is the story of how I came to be profoundly disillusioned with the modernist photographic tradition. Through careful study of their work, it came to my attention that Eugène Atget, André Kertész, Brassaï, Robert Doisneau, and Henri Cartier-Bresson, men whom I had once taken for heroes, were involved in the systematic corruption of the tradition they had helped found. The story I have to tell is complicated. To tell you the truth, there are times when even I’m not sure I understand exactly what it is I’ve stumbled upon. But I have rehearsed it enough times by now to be able to make it as clear as possible. You see, this is not the first time I’ve tried to tell this story. For nearly two years, I’ve been sending versions of what follows into the most important photographic journals and magazines. As you might expect, the photographic establishment, which has so much to lose from what I’ve uncovered, has been unanimous in its rejection of my articles and essays on the subject. Before I go any further, then, I would like to make it clear that I have no wish to compromise the art form to which I have dedicated a great many years of my life. It is my sincere hope that by publishing here the establishment will cease to turn a blind eye to the corruption of its forbears. If photography is to have any future at all, the grotesque deceptions of its past must be exposed and these traitors disowned.

Let us start with these two men.

The man on the right is André Kertész. Born in Hungary in 1894, he moved to Paris in 1925. There he made his name and took many of his most famous shots. Ten years later, with the Nazis knocking at the door, Kertész moved to New York with his wife, Elizabeth. His work was a towering influence on photographers such as Brassaï and Cartier-Bresson; his oeuvre amounts to nothing short of a magisterium of modernist photography. “We all owe something to Kertész,” said Cartier-Bresson.

Strictly governed by the geometry of the modern city, his photographs are filled with their own special brand of visual pun — always aptly-chosen, never cheap. Kertész is the proclaimed poet-photographer. Everything in his work is determined, though nothing shows any sign of constraint. His photos operate within a rigorous visual meter, yet somehow escape the tyranny of the photographic surface. Simply put, Kertész asks us to look deeper than most. The trouble is that if you look too deeply, you end up seeing things which maybe you don’t want to see. Things you shouldn't see.