Five Questions with __________ is an experiment with flash interviews. The series on poets continues with poet, translator, anthologist, editor, and educator Jerome Rothenberg. I first read Rothenberg's celebrated collections rather blindly, long before I knew enough to know about him: first, in a linguistics class, the seminal compilation Technicians of the Sacred: A Range of Poetries from Africa, America, Asia, Europe and Oceania (UC Press, 1968) and much later on his blog Poems and Poetics, conceived as ‘a free circulation of works (poems and poetics in the present instance) outside of any commercial or academic nexus.’

Samizdat devoted an entire issue to exploring Rothenberg and Pierre Joris' poetics after they jointly edited the anthology Poems for the Millennium, Volumes One and Two (1995). Robert Archambeau commented in the editorial note:

In our own time the discourse about poetry, if not poetry itself, seems to have suffered through a taming and truncation of possibilities similar to the one Rothenberg and Joris saw in the years after World War II. I don’t think we’re about to see anyone offering as narrow a version of poetry as Winters offered in his little anthology. But the easy division of poetry into mainstream and otherstream, into Iowa school and Buffalo school, into confession and langpo, has become stifling. The two party version of poetry is about as satisfying and representative as the two party version of politics.

Poets of any language and place should beware the ‘taming and truncation of possibilities’ but arguably none more so than poets writing in English in the United States of America. Rothenberg’s efforts trump the limits of geopolitics without discarding cartographies of power, rooting poetry across/beyond location and historical time (if ‘trans-millennial’ does not exist, can we coin it?).

When the consequence of such a project reverberates as widely as it has, it is doubtful whether stated intention matters. But he has claimed that intention as an intensely personal one, connecting his enthusiasm about the poetry of North American Indians—‘a high poetry and art, which only a colonialist ideology could have blinded us into labeling “primitive” or “savage”’—with his own ancestral lineage ‘in the world of Jewish mystics, thieves and madmen.’

What has most surprised you about the primordial questions that have concerned poetry, or poetry's primordiality itself?

The surprise came early & only grew stronger during those years when I myself was coming into poetry. What had preceded it was the idea of poetry as a late & culturally exclusive process, confined to the developed world & absent or defective in the rest. The turnabout, as it came to me & others, was that poetry in fact was everywhere & was probably coterminous with our earliest emergence as “knowing humans,” strongest often where we least expected it. For that Technicians of the Sacred in 1968 marked my final turning point & allowed me to declare, right from the start, that “primitive means complex” & maybe more so than so much of what we took for granted as our own.

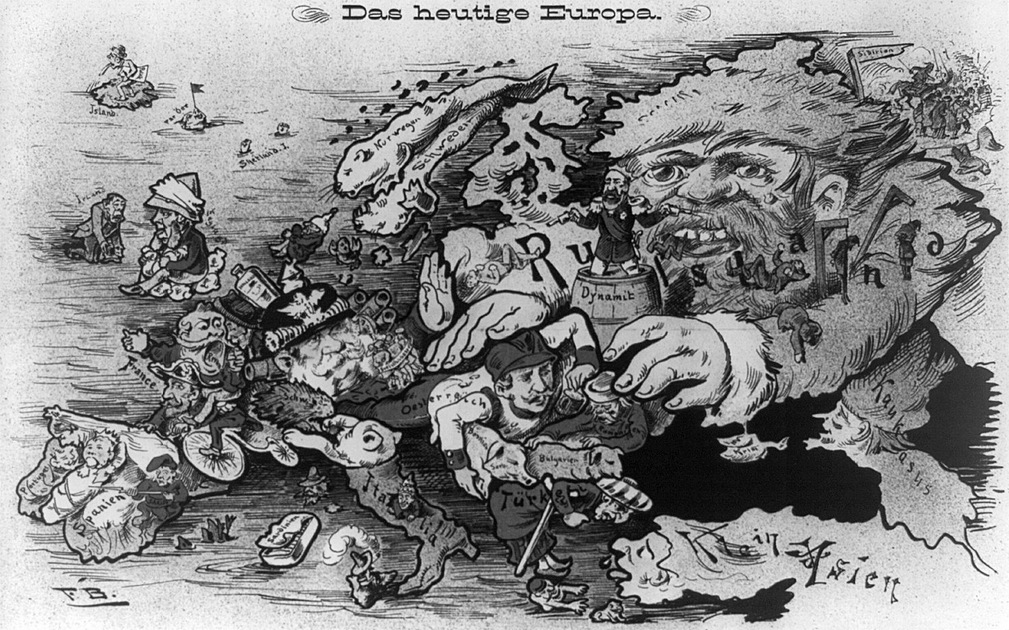

If maps are drawn by those who happen to be in power what happens to those without it?

Maps mean the legislated or regulated reality that the powerful create & enforce against the powerless. The results for those ground down by them are devastating, excluding them, if left unchallenged, not only from any viable political geography but from any mental or spiritual terrain of their own devising. Against this one can think of many forms of resistance, for myself & others a part of what we mean when we speak, as we often do, of a poetics or an ethnopoetics as a remapping of what was foisted on us as the only true tradition. I don’t know what kind of power comes with that kind of mapping, only to say that mapping as a process is at the heart of what we do . . . or should be.

What are the forgotten or underrated virtues of domesticity?

A question like that has my head reeling, the more I think of it. While it hasn’t often come into the writing, for me at least there has been an incredible domesticity, a friendship & love at the center of my life, & its duration over time has gone beyond the boundaries of what I ever thought was possible. At the end of the pre-face to Technicians of the Sacred—some forty years ago by now—I recognized “the-woman” & “the-child” as central both to my own life & “to the ‘oldest’ cultures that we know.” Where it works (& more often than not it probably doesn’t) there is a precarious stability that comes with it & a kind of love more agape than eros—if we mean to set the two apart. I remember that I shared that concept too with Robert Duncan in his declaration of himself as “householder” & life-long companion in his love for Jess, like mine for Diane. And if my poetry is mostly pointing elsewhere, on its softer side I sometimes open up to that domesticity or think I do—as in this poem in A Book of Concealments (“for Diane’s birthday” 2002):

THE TIMES ARE NEVER RIGHT

Warm days are hanging

over San Diego,

where streets

slide into murky

canyons. What

is this but

home & what

is home

but a misnomer?

Pisces has shifted

into Aries.

Aggravated

bumps shadowing

the server’s

arms are no

concern to anyone

yet called to our

attention show

a strain, a fearsomeness

hard to conceal.

The times are never right.

A skin of air is over

everything. The sun

flows like a liquid,

all the universe we see

has never happened.

There is no truth to time

except for birthdays.

In a city under siege

a ceremony

gathers, scattering

the birds.

We live forever

in the instant,

in the house we share.

A groom & bride

are figures,

smaller than a thumb

& little reckoning

how short

the passage between

death & life.

What was your strangest archive experience?

Maybe not “strange” but the most personal one came in 1988, when I went to the small town in Poland, Ostrow Mazowieck, which my parents had left in 1920. I had gone there for the first time the year before, but this time we were accompanied by a young Polish interpreter, who led us to the Town Hall, where I was looking to find any record I could of the family that my parents had left behind them. Those who were alive at the time of the Second World War had all been killed, as far as we knew, at the death camp in Treblinka, thirty miles away, which we had visited the year before. The woman in charge of birth & death records was suspicious at first—wary I think of people searching there for reparations or lost possessions—but as we talked with her that seemed to fade away. The very large ledgers she brought out for us were written, earlier in Russian & later in Polish, & what we were able to track down in the short time we had was the official record of my grandfather’s death in 1920. I had been named for him, but his name as it appeared in Polish was different from what I knew—Juszek Dawid rather than Yosef or Yosl—& his occupation was listed curiously as student or scholar, with some reference I thought to his absorption in talmudic studies as a follower of the (hasidic) Radzyminer rebbe. I also found his father’s name, Szmul, & his mother’s, Marjem Fejga, which I hadn’t known before. For the rest the town remained a mystery to me. I located the street on which my grandparents had lived & where they had a bakery, but the house itself was gone, as was the Jewish cemetery where they might have been buried, now turned into an outdoor market place & parking lot. So the copy of the death certificate that the Town Hall people made for me was the only sure connection I had to that place & time, but more than I had counted on.

Since Lorca's real burial place is still a mystery, what real or imaginary location might we imagine instead?

Maybe the mystery is better to keep than the bones or ashes of the burial place, & the imagination, whenever I call on it, keeps flashing back to the still living Lorca, which is what I really want to conjure up. As an actual gravesite I think of him among so many other unnamed victims that I can’t start to count or figure out which bones are his. The French word tombeau, if I remember right, is both a tomb & a kind of poem or musical composition, an elegy, to house the spirit not the body of the dead. (Mallarmé, say, has tombeaux for Poe & Baudelaire, as also for his own dead son.) For myself it’s the Lorca Variations that would be my tombeau for Lorca, his words fusing with mine, as long as I can keep him living. So:

CODA: THE FINAL LORCA VARIATION

The end for Lorca comes

only when we let it helpless

with insomnia

we hear him stir we see him

reach for Saturn

rising overhead.

No homage can repay what we have lost

our false beginnings naked crystals

bathed in the imagination

needles that sting us, rubber

that brings us down

a rooster who cries against his shadow.

Where it still smells of almonds

dogs are howling

at the moon eclipses in the water

olive trees for Spain

& castanets

our homages stuffed into yellow baskets

offered to Lorca’s Spain.