Of all the ways to account for the sudden jolt of mass uprising in Brazil recently, none has been more consistent than the metaphor of a sleeping giant rousing from sleep. A re-appropriated Johnnie Walker ad literalizes the point: ‘The Giant Awakened’ (O Gigante acordou), adopts the simple technique of divulging newspaper headlines against a black backdrop. The headlines detail the squandering of public funds, defenselessness against violent crime, the indignities of incarceration, lack of access to adequate hospitals, and child hunger, before a green giant—whose body is made up of the rocky green coast of Rio de Janeiro that, freshly détourned in the ad, stands in for all of Brazil—takes its rightful place among the walking living.

http://youtu.be/cK7Onvocbgc

Brazilian journalist Maria Caldas, called the mobilizations the ‘end of autumn, [where] Brazilians awaken to their present.’

Eliane Brum, one of the boldest living writers in the country, wrote a column called “How Much Do 20 Cents Cost?” referencing the initial spark: ‘What is so threatening in these 20 cents, to the point of making governments of the democracy carry out scenes from the dictatorship, is probably something that was believed dead here: utopia. The dangerous news announced in the streets, the new development that the State tried to smash with the hooves of São Paulo police, is that, at last, we are alive.”

None of this happened overnight. Not even the first isolated rumblings of discontent in early June account for it, though certainly the abject violence that police unleashed on demonstrators on June 13 had a powerful effect in galvanizing the so-called sleeping giant. Witness the famed photograph of a woman shot in the face with a gas hose at point-blank range, the open space around her aggrandizing the police’s unbridled use of force. Brazilian television anchors, who barely disguise their hatred of ‘masked youths’ at demonstrations, are wont to point out how the polícia militar are lock, stock and barrel armed and helmeted for warfare. (Appropriately, photographer Victor Caivano has experience shooting both the Afghanistan and Iraq Wars.)

Before going further let me be open and frank: I find it difficult to write about Brazil. I have spent a decade of my life in relation to the country in some way—living in Brazil (first as a student of Portuguese), writing from Brazil (South/South was begun in Rio de Janeiro), or writing about Brazil (a major portion of my dissertation, a forthcoming collection of poems, etc.). I don’t find that it gets easier. It has always struck me, despite its famously syncretic and combinatorial cultural aesthetics, a complete world in and of itself. Its history of enslavement and disenfranchisement and brutality runs deep, as do stereotypes about the acclaimed happy outlook of its denizens (football; sun; bronzed asses; what’s not to be happy about?).

That Brazil has been flung into a global proscenium, first since the rise of a liberal democratic process after decades of military regimes, then following its status as an ‘emerging growth market’ under Lula, has not made the frustration (‘how to talk about Brazil in just so many words’) a lighter affair. You feel the ricochet of Economist-y headlines bloviating about Brazil’s ‘rise,’ that triumphant clasp of the market. It's endless, nauseating, and often dishonest. Yes, there has been a rise—but what the events of this month show is that the Brazilian people will not have their intelligence insulted about who has benefited the most from it, and at whose expense.

Five P’s: public space and services, property, politicians, police, and press.

PUBLIC SPACE & SERVICES

Before it was called the ‘Cidade Maravilhosa’ (give or take, ‘Wonderful City’), Rio de Janeiro’s nickname was ‘Cidade da Morte’ or City of Death. The urban planning undertaken under Francisco Pereira Passos (1836-1913) was largely structured to mirror an image of prosperity—certainly not death—to the outside world. (This obsessive drive to locate and project progress brought with it a high social cost, namely the creation of favelas or informal housing structures all around the city.) Pereira Passos’ urbanism overwhelmingly favored private developers, as well as wealthy citizens and international tourists, and that legacy resonates in contemporary Rio.

In other large metropolitan places, too, transportation to and from the city became as important as the architectural and urban transformations themselves. Mobility and livelihood became intrinsically linked and remain so since. It is no surprise, then, that the flicker that struck the match is rooted in public service transportation. Capital has been invested to benefit housing and leisure for the wealthy since earliest urbanization efforts: it did not begin with FIFA, though the major sporting events of 2014 and 2016 grossly amplified its effects. (No coincidence that ‘the largest protests are happening in cities which will host the World Cup games,’ activist Fabio Malini told the New York Times). Active circulation is far more crucial than the stadium structures that will be promptly vacated, and Brazilians know it. While the favelas frequently suffer the deadly effects of mudslides and floods, for example, development projects speed ahead.

Érica de Oliveira, a 22-year old student and activist told the New York Times: ‘Today’s protests are the result of years and years of depending on chaotic and expensive transportation.’ Indeed, the Free Fare movement (Movimento Passe Livre or MPL), the National Assembly of Students (Assembléia Nacional de Estudantes or ANEL), and other groups have been organizing for at least a decade on the ground. The dispersal of dogged work in various cities is important, as is the egalitarian form of activism such work has taken (the MPL, for example, is an independent, horizontal movement, and Brazilian politicians swooping in to claim they’re in talks with their leaders have fooled few).

Here is what some of that dogged effort has reaped: at Pinheiros metro station in São Paulo, a stirring rendition of the Brazilian national anthem sung ensemble. It's not a cheap attempt at nationalism but a palpable, unifying public energy few have witnessed in recent years.

The last time Brazilians occupied public space in large-scale numbers was in 1964, 1983, and 1992. In the latter, arguably the largest mass demonstration in modern Brazilian history, a mass rally demanded the impeachment of President Fernando Collor de Mello.

'I haven’t felt a sense of union and common good like this since the protests against [Collor] in 1992. It’s a real test for our democratic institutions.' (Theo Ueno, SP in BBC)

The cronyism of the Collor administration shook the entire country, including an indignant leader of the Worker’s Party named Luís Inácio da Silva, who had lost to him in the ’89 elections.

Nearly two decades later, at the 2007 preparations for the Pan-American Games under Lula’s presidency, a new motto for Rio was announced. From Cidade da Morte to Cidade Maravilhosa to... 'Esporte quer dizer futuro' (Sports Mean Future). The president of the Copa do Mundo boasted, ‘We will have a constant flux of investments. The 2014 World Cup will allow Brazil to have a modern infrastructure. In social terms, it will be very beneficial. Our objects is that Brazil become more visible in the global arena. It will be a tool to promote social change.'

It is not only Lula and Dilma Rousseff's trenchant alliance with the global sports oligarchy at the expense of public benefit that is notable. ROAR Magazine:

The symbolic alliance between Lula, the hero of the labor movement of the 70s and 80s, and Paulo Maluf, the last presidential candidate of the moribund military regime, shows that the political class is just interested in power itself and does not have an actual political project to offer. But thanks to them and their watchdogs inside the police force, the 'movement of the 20 cents' is becoming a movement allowing us to say what we think, to assert the right to say that one wishes to live in a real democracy.

PROPERTY

Rio’s first ‘mega-event’ was the South-American football championship in 1919, where the European construction of a stadium was adopted. The construction of the Laranjeiras Stadium involved the destruction of an important downtown historic center, as have various landmarks since.

Brazil, like the United States, is a hugely property-conscious society—probably no coincidence that both countries accounted for a large portion of the transatlantic slave trade when human beings were converted into chattel. Ideological convictions about property’s supreme value run extremely deep. An attack on property is quickly ascribed to ‘violence’ even if no individuals are hurt or injured, and in my experience of watching events unfold this month, that has been near-universal.

What structures are being taken by the people? The Legislative Assembly in Rio, a symbol of entrenched government power, was among the most spectacular building. An announcer talking over this footage moans, 'You will lose all popular support! This is the house of the people! The house of democracy!' He even concern-trolls the demonstrators about what will happen to them: 'the cops will arrive and smother you with tear gas and bullets' (one of the more remarkable things about Brazilian media—perhaps even more than their dribbling counterparts in the United States—is their open, near-total devotion to authoritarian power).

http://youtu.be/XUcRSOiYyow

If this is the 'house of democracy' being attacked with such hatred, doesn’t that make the cause for hatred infinitely more important? Whose notion of property, access, and secure means is really being upheld there in the first place? And wouldn't such a house belong to the people anyway?

Brazilian friends instead chose to focus on its symbolic meaning, describing it to me as ‘queda de bastilha’ or ‘tomada de bastilha,’ the fall or storming of the Bastille. After all, the downtown Palácio Tiradentes which was the site of a large demonstration was, like the Bastille, also converted into a prison.

POLITICIANS

Like many countries today, Brazil is living through a civil war between the state and the people. This war, up until a few weeks ago, was taking place without much noise; but was in no way more peaceful than it is now. For over a century, Brazil has been governed by politicians who see the revenue from taxes payed by their citizens—those who they ought to represent—as a mere bank account. Entire states belong to a certain group or a political dynasty; families who, before being elected to office, had already been the feudal lords of enormous latifundios, with family trees as old as the arrival of the Portuguese in Brazil. In Brazil, more than anywhere else in the world, the oppressors of today are the oppressors of tomorrow.

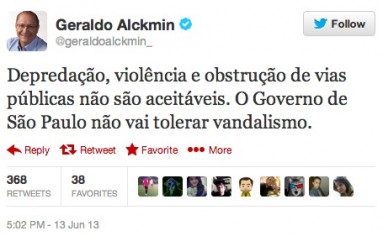

From a pretty perch in Paris, at the height of some of the worst skull-cracking visited on Brazilian demonstrators, Geraldo Alckmin tweeted, ‘Depredation, violence, and obstruction of public paths are unacceptable. The Governor of São Paulo will not tolerate vandalism.’

Some politicians, especially those of the center-right and center-left fearful of losing electoral seats, rushed to validate 'peaceful' and 'legitimate' protests.

Some politicians, especially those of the center-right and center-left fearful of losing electoral seats, rushed to validate 'peaceful' and 'legitimate' protests.

FIFA, a species of Second Estate nobility at this point, ‘expressed “full confidence” that Brazilian authorities have shown they can manage disorder in the streets.’

As if in response, deputy minister of communications Cesar Alvarez braved at a FIFA media briefing at Maracana stadium, ‘I would not say we have lost control, no.’

Protests coincided with the Confederations Cup, a preamble to the World Cup championship. Demonstrators in the tens of thousands gathered outside stadiums in Rio and Brasília (the stadium here is among the most expensive of the six new ones built, costing nearly $600 million), exactly the sites the government hopes to show off to nervous investors. The armed guards that FIFA has hired to protect its stadiums from mass movements such as this one are rarely written about; despite their presence, people have kept up the momentum.

Inside the Confederation Cup's opening event, President Dilma Rousseff was booed.

POLICE

[6/17/13 9:49:59 PM]: A coisa tá feia no rio [things are ugly in Rio]

[6/17/13 9:50:13 PM]: Policial disfarçado de civil [police disguised as civilian]

[6/17/13 9:50:31 PM]: Tiros com balas de verdade [shots with real bullets]

One of the major frustrations of ordinary people in Brazil—this could be true of a multitude of societies—is how the country is seemingly over-weeded and devoid of law at the same time. This national bête noire stretches across personal and political persuasions.

The mobilization got the name ‘vinegar revolt’ from reports of police confiscating the protesters’ only form of self-defense against tear gas. A filmed exchange between CartaCapital reporter Piero Locatelli makes the jolting, overbearing presence/absence of law apparent.

Locatelli is stopped and asked why he’s carrying vinegar. He answers it’s because of the sickness he incurred from inhaling tear gas the ‘last time I was doing my job.’ The officers freely allow their name tags to be filmed: someone gave them these orders, and they’re very confident in what they’re doing (one mumbles, ‘I’m receiving an order’). Locatelli is taken to a police captain who many YouTube commenters believed to be ‘visibly drugged out.’ The journalist is detained and shuffled away.

At a press conference following the incident—undoubtedly this media exchange existed solely on account of filmed evidence, and because card-carrying press was involved—lieutenant-colonel Marcelo Pignatari voices gravely, ‘There was a substance with him that he alleges is vinegar. It will be submitted to the police for confirmation.’ A substances he alleges is vinegar. Before signing off, Pignatari answers a journalist that no, vinegar is not a banned or controlled substance. Yet you can’t blame the journalist for asking. The entire incident is a fascinating encapsulation of how unwritten law operates in practice, and whose bodies, rights, and livelihoods are trampled in the process.

The brutal and grotesque use of tear gas and rubber bullets against unarmed civilians last week was but another incident of police violence in what is a decades-old phenomenon (and one that arguably has its roots in slavery in Brazil). Throughout the twentieth century, police violence was a feature of arrests and crowd control, especially in poor areas. Even in the 1960s, police death squads operated in favelas during the military regime, prompting the press to distinguish between death squads against “criminals” and torture against political prisoners. The end of the dictatorship did not bring an end to such violence, in no small part because such violence well predated the military regime of 1964-1985, and such violence has continued to define police tactics and methods throughout much of urban Brazil well into the 21st century.

Few in contemporary Brazil can forget the massacre of Carandiru, which as I previously discussed saw its overseers not only go virtually unpunished but receive cushy government appointments.

Police executions in ordinary life were called ‘premeditated’ and ‘calculated’ in a BBC report: '[E]xecutions by death squads appear to be a traditional feature of Rio policing.'

Such historical attributes put atrocious police abuse, including the use of live assault rifles and ammunitions, into perspective.

PRESS

My number-one enemy in Brazil is the Globo media conglomerate and every residual outfit like it. The media operate as a disgraceful aristocracy. Ownership of the networks is in the hands of a few extremely wealthy families. Admittedly coverage of the most asinine events physically repulses me.

Little wonder that on Monday the World Cup site was hacked and replaced with a promotional video siding with the demonstrations. The Brazilian government’s own World Cup site was hacked for hours. The Twitter account for Veja—a Newsweek or Time equivalent, but with more bared teeth—was also hacked, to great jubilation.

Disdain for the media didn't happen overnight, either. In 2011, a pride march extracted a Globo reporter from their sights with the chorus ‘O povo não é bobo, fora Rede Globo’ (the people aren’t stupid, get out Globo Network).

http://youtu.be/SZjaJ2AOvvM

Distressingly, serious investigative Brazilian journalists and bloggers who diverge from the servile interests of the mainstream, corporate behemoths are routinely attacked. Brazil holds the fourth highest total number of journalist murders in the world (see Committee to Protect Journalists’ 'Where Journalist Murders Go Unpunished').

The greatest illustration of mania this week happened on José Luiz Datena's show on Globo’s Globo's competitor Bandeirantes. Few have dared to insult the intelligence of every single living Brazilian with Datena's stumbling ineptitude. Datena asked viewers to call in voting whether or not they are in favor of this form of protest (‘Voce é a favor deste tipo de protesto?’). Disappointed with favorable results, he egged on, ‘I would vote no!’ The ‘sim’ votes rise wildly to risible horror.

Idiocy was not restricted to the national news.

Every day this movement grows is a thorn at the side of the market boosterism of the past decade and a chance for greater dignity.

Addendum: Carla Toledo Dauden’s highly effective video ‘No, I’m Not Going to the World Cup’ has made its way around the world a few times already, and doesn’t even rely on showing severe police repression to make its point. It is well worth viewing.