In America of yesteryear, you often had to be sick to eat well

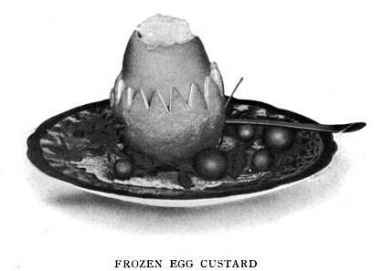

Images from Fannie Farmer's Food and Cookery for the Sick and Convalescent (1907)

You have to feed a flu and starve a cold, the saying goes. I've never been one to insist on such distinctions. When I get sick, I feed. Nothing makes my appetite go viral like a cold or flu. This otherwise unpleasant condition becomes for me a sort of camphor-scented Carnaval, a brief time when forbidden foods are not only permitted but altogether transfigured, acquiring healing powers unknown to me when well. Fever calls for a chocolate bar taken every two hours, a sore throat for a banana shake sipped as needed.

"Exuberant health is always, as such, sickness also." --Theodor Adorno

The staunchest resistance mounted by stuffed sinuses melts when met with a buttery toddy. Apricot conserve eases the worst miseries of congestion. The medicinal properties of milk are well known, but they require vodka and Kahlua to activate them.

Historical precedent clearly favors my approach. Illness has long occasioned dietary indulgence.

"What was life? It was warmth, the warmth generated by a form-preserving instability, a fever of matter, which accompanied the process of ceaseless decay and repair of protein molecules that were too impossibly ingenious in structure." --Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain (1924)

"If any member of a family was taken ill," recalls Phillis Browne in her 1882

Girl's Own Cookery Book, "the cousins and the aunts, but especially the aunts, used to come round at once with superlative molds of jelly, as furnishing undoubted proof of sympathy and affection." These doting aunts likely consulted one of the many cookbooks devoted exclusively to invalid cuisine, a subject of such importance that even cookbooks concerned with other topics dedicated at least a chapter or two to it. These books sought to infuse tender loving care with practical know-how. "Ignorance in a sick-room is very objectionable," cautions John Fothergill in

Food for the Invalid, the Dyspeptic, and the Gouty (1880), "even when combined with any amount of family affection."

"Neurotics complain of their illness, but they make the most of it, and when it comes to talking it away from them they will defend it like a lioness her young." --Sigmund Freud

Like anything done out of affection, preparing dishes for invalids often put skill and patience to the test. It took a most fastidious cook indeed "[to] arrange the invalid's tray as daintily as possible," as one cookbook prescribes, and to see to it that the tray thus arranged also be piled with "plenty of fresh, clean towels" and delivered in silence by a bearer skilled enough to avoid "any exaggerated efforts at being quiet." The food itself could be neither too hot nor too cold, its portions neither too ample nor too scant. It had to be nourishing, palatable, and fresh. And though experts deemed simple dishes best, they did encourage novelty. Meals ought to contain unexpected delights. To this end, invalids were kept wondering. "Never consult a patient as to his menu," advises Fannie Farmer in

Food and Cookery for the Sick and Convalescent (1907), "nor enter into a conversation relating to his diet, within his hearing."

"It is in moments of illness that we are compelled to recognize that we live not alone but chained to a creature of a different kingdom, whole worlds apart, who has no knowledge of us and by whom it is impossible to make ourselves understood: our body." --Marcel Proust

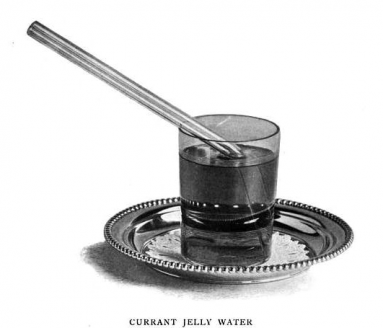

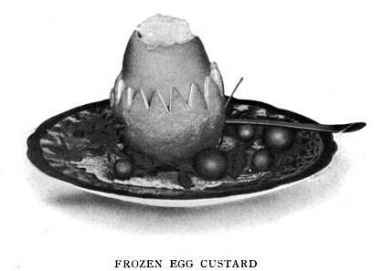

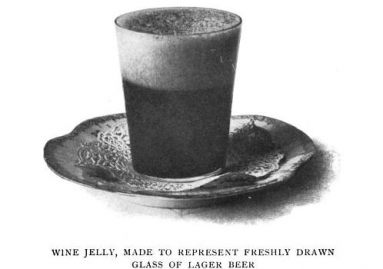

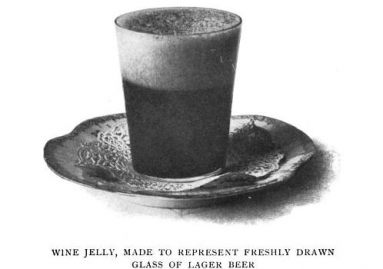

Patients may have been kept ignorant, but the result was bliss. Many of the prescribed meals might please modern palates. Egg nogs, boiled custards, fruit jellies, port-wine lozenges, baked apples and other dainties found their way on trays. Savory fare didn't disappoint either. Crispy strips of broiled bacon, piquant raw beef sandwiches, tender mutton chops -- these the turn of the last century's infirm would wash down with fruit squashes, lemonade, and brandied cocoa.

"If thou could'st, doctor, cast, / The water of my land, find her disease, / And purge it to a sound and pristine health, / I would applaud thee to the very echo, / That should applaud again." From Macbeth, Act V, Scene III

The unwell ate well -- often better, at any rate, than did those in perfect health. "In feeding the sick, strict economy should be considered only when necessary," notes Farmer. Her "Cup St. Jacques" calls for lemon, orange, and strawberry sorbet. These were doused in Maraschino cordial, garnished with banana slices, candied cherries, and Malaga grapes, and served in champagne flutes. Another concoction requires a planter's worth of ice cream be sprinkled with vanilla chocolate and topped with a bloom. Christened "Flowering Ice-Cream," this Farmer recommends to "patients, especially children," who show "little appetite."

"Some perishing of pleasure -- some of study -- / Some worn with toil -- some of mere weariness -- / Some of disease -- and some, insanity -- And some of wither'd or of broken hearts." --From Byron's Manfred (1816)

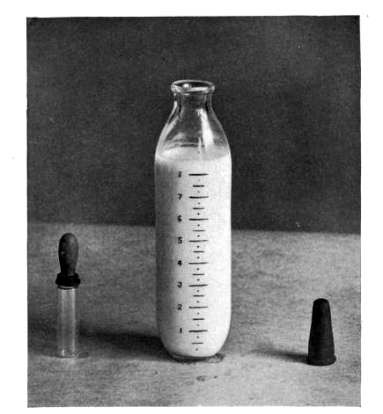

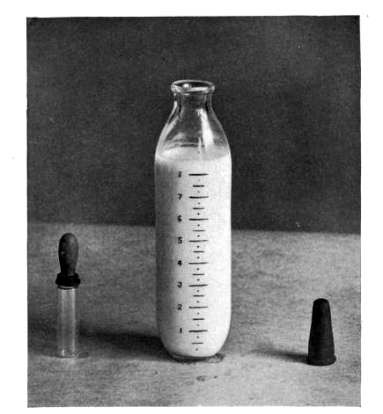

Such treats as Cup St. Jacques and Flowering Ice-Cream appeared bedside but rarely. The bulk of invalid recipes likely didn't do much to make little appetites big. Toast water, chicken oatmeal, egg coffee, peptonized milk, raisin broth, and cracker mash were all foisted on the sick. Gruel lurked everywhere. Therapeutic jellies numbered as the stars. These latter were distilled from calves' feet, chicken parts, mutton shanks, Irish moss, sago, oranges, and tapioca, among other things. When there weren't jellies or gruel, there was fermented milk. One version of this drink, koumiss

Toward the end of the 19th century, koumiss had gained a strong enough reputation as a cure-all to support a small industry resorts in southeastern Russia. There patients were furnished 'with suitable light and varied amusement' during their treatment, which consisted of drinking large quantities of the stuff. Both Tolstoy and Anton Chekhov attempted this cure. In 1901 Chekhov checked into one such resort, hoping to remedy his tuberculosis. He drank four bottles a day, gained 12 pounds, but, alas, found no cure.

, many home economists believed a cure-all. "Home-made Koumiss is most satisfactory," writes Farmer, who offers her own version. Yet the scientific-cookery maven's mild, saccharine drink bears little resemblance to the tangy equine elixir enjoyed by Tolstoy.

Through times of war and peace, invalid cookery endured. Nurses caring for troops injured in hostilities between the northern and southern states were encouraged to prepare meals "in an inviting manner" and to ensure that "everything ... be perfectly clean and nice."

The wounded and sick ate better than their caregivers. A nurse at Mansion House Hospital in Alexandria, Virginia wrote that her food consisted of "nothing but coffee (so poor and with hardly ever milk) and dry bread for breakfast; for dinner bread and meat (and such meat! always the tail or neck or some nasty part), and at night coffee and bread again."

Many tried to uphold this standard. "We give [patients] toast and eggs for breakfast," writes a nurse in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, "beef tea at ten o' clock, ham and bread for dinner, and jelly and bread for supper." A Quaker widow saw to it that wounded Union soldiers enjoyed an abundance of milk and eggs, even going so far as to arrange a supply line of "over one hundred cows and one thousand hens, strung all along the road from Chicago to Memphis." Not all soldiers were so fortunate. The farther south the Northern army pushed, the worse the food became. Wounded and ill Union soldiers in South Carolina, for instance, had to make due with biscuits of dampened flour fried in bacon fat. "If they could be worn as armor, it would make the men invulnerable," remarked Esther Hill Hawks, a New Hampshire native who served as an unofficial army surgeon. "[H]ow it will affect them as rations remains to be proved."

From Hospital Management (1922): "Attractive cards containing the day's menu can be distributed each morning; this will please the patient, but make him twice as pleased with the service by a dainty tray. These details might seem of minor importance in the care of the sick, but a fussy 'half starved' patient does not recover quickly or completely without sufficient food."

Yet poor rations beat no rations at all. Hawks reported that poultry she obtained for sick African American troops "were all eaten by those in the [hospital administration] Office." To add insult to injury, "a box of luxuries sent out to the 54th wounded ... consisting of fruits, jellies, wines and some clothing was disposed of in the same way." To her dismay "the Steward wore the comfortable clothing and the edibles went on the office table!"

As the luckless African American troops discovered, social status decided the quality of care a person might expect. For most, sickness meant lost wages. If they could rally, they worked

"On this occasion, more than once, I left my paper on the cabin table, rushing away to be sick in the privacy of my stateroom," writes Anthony Trollope in his Autobiography (1883). "It was February, and the weather was miserable; but still I did my work. Labor omnia vincit improbus."

. The immigrant laborer Jurgis Rudkus of Upton Sinclair's

The Jungle (1906) must somehow make ends meet, despite being just out of the hospital. The experience proves instructive: "He saw the world of civilization then more plainly than ever he had seen it before; a world in which nothing counted but brutal might, an order devised by those who possessed it for the subjugation of those who did not." One of the latter, Rudkus roams the streets "sick and hungry, begging for any work."

Recipe for Invalid's Jelly from Mrs. Beeton's Dictionary of Every-day Cookery: Ingredients. -- 12 shanks of mutton, 3 quarts of water, a bunch of sweet herbs, pepper and salt to taste, 3 blades of mace, 1 onion, 1 lb. of lean beef, a crust of bread toasted brown. Mode. -- Soak the shanks in plenty of water for some hours, and scrub them well; put them, with the beef and other ingredients, into a saucepan with the water, and let them simmer very gently for 5 hours. Strain the broth, and, when cold, take off all the fat. It may be eaten either warmed up or cold as a jelly Time. -- 5 hours. Average cost, 1s. Sufficient to make from 1 1/2 to 2 pints of jelly. Seasonable at any time.

In this respect we've made little progress. Some 39 percent of American workers in the private sector enjoy no paid sick leave. For workers in low-wage industries, that figure rises to 79 percent. (Their German counterparts, by comparison, receive a lavish six weeks.) An elite may recuperate in leisure. The rest of us stumble to cubicle, console, or counter hoping DayQuil will fetch us from delirium. "It is only when the rich are sick that they fully feel the impotence of wealth," Benjamin Franklin observed. Today it would be more apt to say that it is when the rich are sick that they fully feel the importance of wealth.