When self-medication is an economic necessity, it helps to believe in magic pills

Last spring, my rib cage erupted in splotches. They were red and angry and showed up on a morning like any other. I couldn’t think of anything I’d been doing to cause them. Just going to work, walking the city, seeing friends, writing. Food, coffee, beers. Same lotion and soap as always. I wasn’t even having sex. Drab stuff, my life’s most usual stuff.

Google, after confirming that I meant to type splotches and not blotches, pulled up pages and pages of possible diagnoses. Bug bites, pimples, herpes, cupping bruises, foot fungi, shingles, blistering eczema, various kinds of boils. After scrolling through a few dozen queasy pages of photos, it seemed safe to say that I had hives. All I had to do was figure out what was causing them, and avoid contact with that.

Google had a lot of ideas about what might be irritating my skin. It might, I read, be responding badly to heat or cold, to abrupt switches between the two, to certain foods, the sun, a lack of sun, stress, dust, non-cotton fabrics, pressures, vibrations, animal dander, sweating, insect bites, or some combination thereof. If I could figure out the (probably combinatory) cause and eliminate it, my hives would go away. Clean calm skin, blotchlessness. Maybe I could get it back.

***

The outbreak reminded me of a fight I once had with an ex, an abstract argument about the word health.

Health, he maintained, tended to suggest an objective model of the body, one whose calm organs functioned perfectly and never got excited, cried foul, or revolted. Silent bodies full of peaceful organs. Health was an ideal, stupid about social contexts and constraints, and only a meaningful measure for a very specific subset of people—those with both good access to doctors and the ability to control who and what they came into contact with in the places they lived, met, and worked. That subset is small, and too often determined by race and class and geopolitical distinctions. In his opinion, people with less than perfect medical access and/or less than perfect ability to control their environment needed a new paradigm. Their organs weren’t served by a discourse of purity and control, of perfect silence and peace.

The ex was a health geographer and at the time had been studying disease-prevention efforts in industrial-era tenements. He was interested in the tension between official prevention narratives and the realities of tenement life. One presupposed an individual body whose boundaries could be neatly delineated and protected; the other didn’t and couldn’t. Over the course of the research, he’d made several attempts at articulating an other-than-health paradigm. The best thing he’d come up with was borrowed from a cyber-feminist who liked to talk about social dynamics with metaphors about noisy mechanical channels. He was still vague on the particulars. Noisy bodies, he said, born into noisy environments.

At the time, I found the discussion overly semantic and said so. After my outbreak, though, I thought a lot about what he’d said. Because a good case of hives looks like nothing if not noise. The skin fritzing out in red waves of static: excited, angry, in revolt. And the more I tried to pinpoint the source of the hives, the more I found the pressures my life and environment exerted on my body—all the drab frictions inherent in work, walking, friends, writing—jumbled, loud, and unavoidable.

***

I don't get health insurance through work and can’t afford to pay for it out-of-pocket, so I haven’t been to a doctor in a very long time. This has become enough of a lifestyle that people have started pushing me to visit free clinics or apply for government medical support. I haven’t done either, whether from a twenty-something’s sense of invincibility, an artist’s sense of priority, or a formerly middle-class woman’s uncertainty about the appropriateness of her need. Probably some combination of the three. In any case, my body has, for something like four years, functioned without any input from medical professional or institution.

Over those four years, I’ve been lucky enough to have avoided major illness or injury, and learned, as people who lack access to a doctor do, to treat the smaller ones myself. I’ve gotten used to self-medicating my aches and pains—the sprains, depressions, anxieties, flus—with mix-and-matched doses of alcohol, friendship, romance, sex, food, coffee, writing, sleep, the Internet, exercise, pop music, critical theory, literature, art, TV, astrology, poetry, craft hobbies, thrift store clothing, grooming habits, self-pity, feigned confidence, and actual hubris. Every once in a while I throw in a generic painkiller. Not much else, nothing particularly fancy, and if the combining is done with any dexterity, most of the time it has worked out okay.

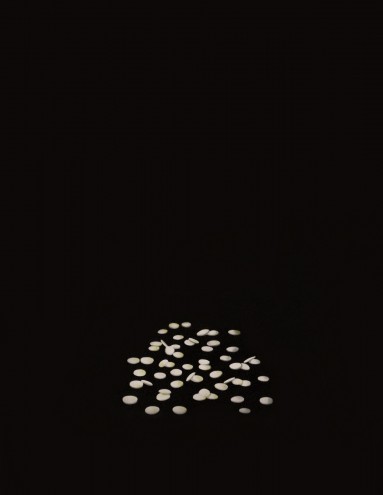

I also occasionally take placebos. About three years ago, I heard a podcast on placebos that said they often work—objectively, medically work—even if you know you’re taking one. I was in the middle of a rough winter, so I started packing pretty silver cake decorations into gelatin capsules and, with my 27th birthday approaching, devised a placebo program to fix it. Hopefully the pills would help start the next year like a remedy. They looked promising. They sparkled like buckshot.

When the program was complete, I kept making more placebos. Five silver balls went in a capsule and made one; five silver balls made two, five silver balls made three; and then four, five, tens, hundreds, slowly filling a line of jars on my kitchen table. When I finally stopped, after a couple weeks of packing, I’d made several thousand. My roommate eventually tapped into the surplus, first to address a romantic flare-up, then for professional strength, for general bravery, to help navigate a familial crisis. Then she started passing them on to others, and they did the same, and after a while they had criss-crossed the country and traveled two oceans, where people we knew swallowed and distributed them for things like nagging doubts, a divorce, creative stagnancy, loneliness, a contentious union campaign. We had endless things to repair, it seemed, and the pills had a suggestive way of traveling.

An obvious (if symbolic) lesson was suggesting itself: Medicine is social—which, as far as I understand, is the broad-stroke point to the science of placebos. Social ritual, suggestion, and approval undergird every gesture any of us make to maintain our bodies—even for doctors tasked with working toward a body’s healthy best. My experiment in self-medication became one in community medication without even trying, which echoes back subtly to my ex’s argument. If, as he proposed, common parlance imagines that healthy bodies are individual bodies, lacking cultural context and stocked with perfect model organs, he was probably right to ask for another language.

All my self-medicating has been in some sense social, and every gesture of maintenance and repair I’ve ever performed on my uninsured body has been nothing if not a conversation. Sparkling communal buckshot, social vibrations passing through porous, porous skin.

***

After conferring with Google, I went to work to get rid of my hives. I observed my body closely and asked questions like a doctor. After a couple of weeks I felt confident identifying a few major sources, and several more minor ones. Major: heat, sweat, and abrupt temperature changes. Minor: dust, animal hair, and tight and/or non-cotton clothing. My life at the time, unfortunately, seemed to contain only those things. At the cleaning service where I work, clients wanted thorough spring-cleans of their filthy city apartments. I spent 10-hour days collecting cat hair out of lead-painted radiators and scrubbing oily dust-sludge from cabinets. At home—I didn’t have one, and was having trouble finding anything affordable. In the meantime, I spent two months couch-surfing with kindly friends, all of whom seemed to have pets. Temperatures outside were unseasonably hot and humid, while subway cars and the places I cleaned were air-conditioned to an arctic crisp. I walked, biked, sweated profusely. My skin over-heated and cooled and slicked and the pet hair stuck to that and then the dust. The hives flared beyond my ribs up my back, made happy encampments in my armpits. The only irritant I managed to control was the cut and fabric of my shirts. Lucky for me, loose, tent-like cotton shirts were trendy for the summer and everywhere, circulating so quickly that they could already be found in thrift stores. I bought three, rotated them, and crossed my fingers. There wasn’t much else to do. I was running up against one of the other socials that act on the body—the socioeconomic—and my best medicine was only so good.

Eventually I started taking placebos again, just for good measure. One a day, mechanically, without belief they could cure anything. My pills—our pills—were lovely but not powerful enough. I started Googling again, probing into the shadows of its search returns, into increasingly speculative advice from increasingly unofficial sources that would have sent me bumbling through endless, experimental gauntlets of anything from acupuncture to expensive vitamins to prayer. I didn’t especially want to try any of it. I also didn’t stop reading.

I comforted myself with a claim that came up again and again, an anecdotal one that was harder to ignore: A lot of people who go to doctors for hives don’t get cured. Their rashes remain angry, mysterious, and stubborn. If I’d had insurance, I might have visited a doctor only to be prescribed a maybe-effective steroid cream and told to do exactly what I was already doing. Making little adjustments, paying attention, hoping.

The skin’s a helplessly permeable organ. Weeks turned into months and the causes and effects of my hives kept echoing through it. Some people have hives for years. I figured I might have them forever and kept popping our pills.

***

I'm wary of striking too cheap an anti-establishment tone here. It would be dishonest for several reasons, most immediately because I probably won’t be uninsured for much longer. The insurance available through my state’s health exchange is projected to be quite cheap, and if all goes well, I’ll buy into it, rejoin the ranks of the insured, and feel grateful for the safety net—for when a major illness or injury finally does hit, for when my blotchiness becomes more than cosmetic, for when my body needs a silver bullet and not just homemade buckshot.

Still, I wonder how best to think about that buckshot and about the informal conversations we piece together to accompany it. They might not fit exactly inside a model language of health, but they’re the chatter that surrounds it, seeping through and modifying bodily ideals that are more porous than we usually admit. What are they doing, if not quite curing us?

***

The hives began to fade a few weeks ago, as fall arrived. Could have been the placebos, though more likely it was simply cooler air. By then I’d almost forgotten they were a bother. The routine of dressing and washing and keeping them cool had become familiar. White noise. They fuzzed around my ribs like a box fan or a bank of fluorescent lights.

I kept moving. I filed the departed rash alongside the other bodily troubles I’d lived through uninsured. I considered and decided against contacting my ex, with whom the official conversation hovers comfortably at non-. Fall wind set everything flapping. I let it clean my ribs.