The Academy has spoken, and now it’s official — animals can’t act. Uggie and Joey

To demonstrate how even a cursory analysis of animal performance can illuminate a filmmaker’s style, let’s take as our examples Jean Renoir and Fritz Lang, two directors between whom the equation has always been easy: Whatever is true of one, the opposite will be the case for the other. If in Renoir’s films we find day, in Lang’s we find night; if in Renoir we find rivers, in Lang we find flames; if in Renoir "everyone has his reasons," in Lang there is no escaping fate. While it may seem a gratuitous extension of this useful formula to suggest that the distinction between these filmmakers is that of a respective cat and dog cinema (not least because, as we all know, cats aren’t the opposite of dogs), it’s perhaps not as trivial a distinction as it may first appear.

This isn't a question of quantitative analysis, as my intention isn’t to prove that there are more cats in Renoir’s films than there are in Lang’s (although there definitely are), or that there are more dogs in Lang’s films than there are in Renoir’s (I’m pretty sure there aren’t). Instead I hope to show that the appearances made by these animals (or lack thereof) offer a model for exploring the differences between these two directors’ styles.

The Renoir-Lang dialectic has already been astutely characterized in Leo Braudy’s World in a Frame, and my discussion of their work leans heavily on his description of their works in terms of an “open” and “closed” style,

Lang, in short, was something of a cinematic tyrant. Working best in the hermetically sealed environment of the studio, he liked (or rather, demanded) absolute control over everything which happened on set. That fate is so often cited as the defining characteristic of his work isn’t simply because of the ineluctable plot twists his characters face (a last-minute death row pardon! An accidental stabbing! Inconvenient amnesia!) but the sense of overdetermination that permeates every shot. The neurotic orchestration of each minor detail gives all of Lang’s films an inescapable visual regime. Whether set in Berlin, New York or London, the city street or the prison cell, his films always unfold in the same place: a geometric nightmare of shadows where it’s always night and time is always running out, a place that has become known as the Langian Universe. In this universe, both onscreen and on-set, no deviation, improvisation or alteration can be accommodated or tolerated, and nothing, and I mean nothing happens by accident. That Lang once spent hours (and allegedly over 40 takes) rearranging a dirty plate and spoon in the background of a scene with Henry “one-take” Fonda, goes some way to indicating the maddening level of precision he required in his work.

So how did Lang even begin to introduce animals into such a rigorously controlled environment? Badly. The director killed three horses while shooting his first western, The Return of Frank James as they, like the crew, were denied the luxury of meal breaks during the demanding shooting schedule. On his second western he had no better luck, infuriated that cattle were ruining his shots by refusing to move three feet to the left. Although the romantic frog lovers in You Only Live Once leap into their pond home perfectly on cue, they were encouraged to do so with the help of an electric shock, which Lang had rigged up specially to overcome their frustrating inability to follow direction.

But note how (with no electrodes required) Spencer Tracey’s canine companion executes a well-timed escape from the jailhouse fire in Fury by leaping through the cell door, how with ease and elegance the dogs owned by the Nazi spy in Cloak and Dagger ensnare Gary Cooper perfectly in their leashes at exactly the right moment, or how the hunting dogs in Manhunt follow their prey with such absolute focus. That Lang favored the artificial and contrived over the natural and unaffected, that he expected his cast, whether animal or human, to be tractable, servile, and obedient at all times, meant that few animals or actors were welcomed so readily into the Langian Universe as dogs, whose tireless subservience suited his dictatorial style perfectly.

Cats, on the other hand, unpredictable and downright wilful as they are, did not sit well in the uncompromising regime of the Lang film. It’s not exactly shocking to discover that the only action we see cats perform in his films (and I’ve only counted three in his whole American output), is to dash off-screen as quickly as possible. But in the Langian Universe, nothing happens without a reason, and if a cat runs out of shot, then Lang wanted it that way. In House by the River, the cat jumps from atop a gramophone just as the song finishes, indicating disgust at the murderer we have just seen callously dancing. In Cloak and Dagger, Cooper’s location is revealed to the Nazis by the cat that runs to him across a room, while similarly, in You Only Live Once, a cat leaps from a bed when its owner spies a wanted criminal outside his window and subsequently calls the police. Their actions may be simple (probably motivated by fear rather than Oscar ambitions), but they are in no way insignificant, as each cat’s movement plays an integral part in the trajectory of the scene, catalysing (if you’ll excuse the crudity of the pun) a development in the narrative.

Lang’s is therefore not exclusively a cinema of dogs, but the nature in which the animals in his films perform (the very fact that they perform at all) is indicative of his wider filmmaking regime, in which the natural and unpredictable is transformed into the mechanical, artificial, and predestined. Lang’s films may have featured cats, frogs, horses, and even a few birds (typically flightless ones I might add – as Braudy said, "there is very little sky in most Lang films"), but ultimately his style of filmmaking was one which only truly accomadated a canine style of performance.

Dogs do appear prominently in Renoir’s films too, most notably in Boudu sauvé des eaux, but it’s important to note that Boudu’s dog Black is a lost dog, a mischievous dog, a shaggy dog, and by no means will we find him performing the kind of tricks that Tracey’s dog pulls in Fury. For while Lang’s is a cinema in which everything is fastidiously controlled, chance and fortuity are the organizational principles upon which Renoir’s films operate — which goes some way to explaining the inordinate number of cats we find in his work. But unlike the cats in Lang’s work, whose actions are integral to the machinations of the plot, Renoir’s cats do not perform but simply appear.

For example, in Boudu sauvé des eaux, no feline action propels the narrative in the way that Black’s disappearance does, but instead cats appear in those interstitial moments (often overlooked in analyses of the film) that chart the passing of the day and the movements of the city, sitting on Parisian rooftops yawning, stretching and watching the world beneath them. Similarly, in Une partie de campagne, La bête humaine, and Swamp Water, kittens wander in and out of shot, often in the background or out of focus, clawing at one another and writhing in the arms of their human co-stars, carrying atmospheric rather than narrative weight. Simone Simon’s kitten in La bête humaine certainly forewarns us of her duplicitous affection and fickleness (a feline specialty), but its appearance is hardly integral to the murderous plot which unfolds. No performance is required from this kitten to produce the required effect; no marks must be met, no directions taken. Instead, like all those cats in Renoir’s films, this kitten simply plays itself. (And it’s worth nothing that when Lang remade La bête humaine as Human Desire, not a whisker of that kitten remains.)

The naturalism with which animals appear in Renoir’s films, the ease with which cats are accommodated in his work (not to mention the kisses and hugs they receive), is indicative of his broader approach to the cinematic image, which responds to the contingencies of nature with a fluidity, generosity and warmth entirely lacking in Lang. The potency of the cat as a marker of naturalism is confirmed when one examines the work of both Renoir’s peers and progeny, suggesting that the abundance of felines in his work is not so much an auteurist tick, as a wider national trend, indicative of a peculiarly French style of direction.

Yet anyone familiar with Renoir’s work will protest at the suggestion that cats are central to his relationship with animals, as it would be impossible to discuss his work without mentioning rabbits — or rather, one specific rabbit, who dies in the most central moment of La règle du jeu: in the middle of the hunt, in the middle of the film, right in the middle of the frame.

This single shot (in both senses of the word) refutes any claim I might make to Renoir’s being a cinema of warm accommodation, as the endless number of takes and the unimaginable number of rabbits (or appropriately enough, “kittens,” as baby rabbits are called) that must have been required to capture these final, tiny death throes so perfectly rival even Lang’s cruel demand for precision.

However unaffected the animals in Renoir’s films may seem, however free and unrestrained their actions may appear, the rabbit’s death in La règle du jeu reminds us that filmmaking inherently requires the transformation of the lively and natural into the deathly and mechanical. Like the wind-up toys and taxidermied creatures which populate the château in La règle du jeu (not to mention other Renoir films), once shot and captured, the “real” animals that pass before his lens become just as artificial, as their actions become perfectly repeatable, their images fixed in time.

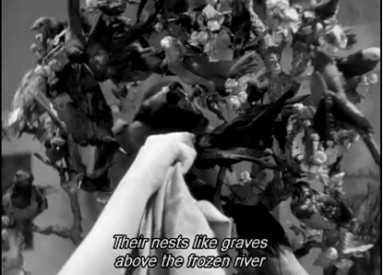

But with the Renoir-Lang equation, whatever we do to one side, we must always do to the other. If Renoir takes a Langian turn with his exacting rabbit execution, then somewhere we must find Lang giving his animals a Renoirian breather. It’s no surprise that the Lang films that contain the most naturalistic animal performances can be found in two of his most unusual and obscure American titles: Western Union and Clash by Night. What alerts the viewer to the fact that these are not typical Lang films are their opening sequences, comprising documentary footage shot on location in Utah and California respectively. That these images of buffalo roaming the dusty plains, images of seagulls, herons, and seals enjoying the waves of the Pacific Ocean, can signal to the viewer so immediately and succinctly that we have departed from the Langian Universe underscores perfectly how closely auteurist style and animal performance are linked.

Admittedly, it’s not as simple as a cat and dog cinema; one cannot characterise a director’s work just by analysing the animals that appear therein. The birds in Malick’s and Hitchcock’s films could hardly be said to signify the same style. But by interrogating the nature of these animals’ performances, we can begin to tease out nuances, similarities, and disparities in these directors’ work. So while there may be no Oscars in store for Uggie and Joey, perhaps it will be some consolation to think that their performative legacies may live on in criticism rather than in the shadow of Rin Tin Tin's award ambitions.