The Gulf Labor Working Group is a coalition of international artists, writers, and activists who since 2011 have brought focus to the "coercive recruitment and deplorable living and working conditions of migrant laborers in Abu Dhabi’s Saadiyat Island (Island of Happiness)," particularly on the workers building the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, the Louvre Abu Dhabi, and the Sheikh Zayed National Museum/British Museum. Their campaign, called "52 Weeks," is a one-year effort whereby contributors deliver a work, text, or action each week, taking as their starting point the exploitation of workers building Abu Dhabi's premier cultural institutions.

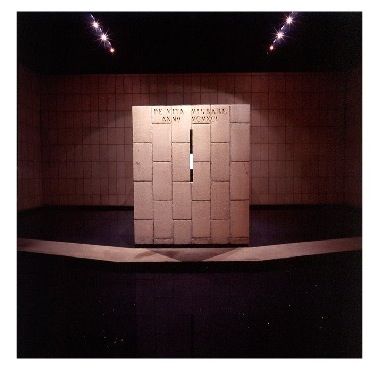

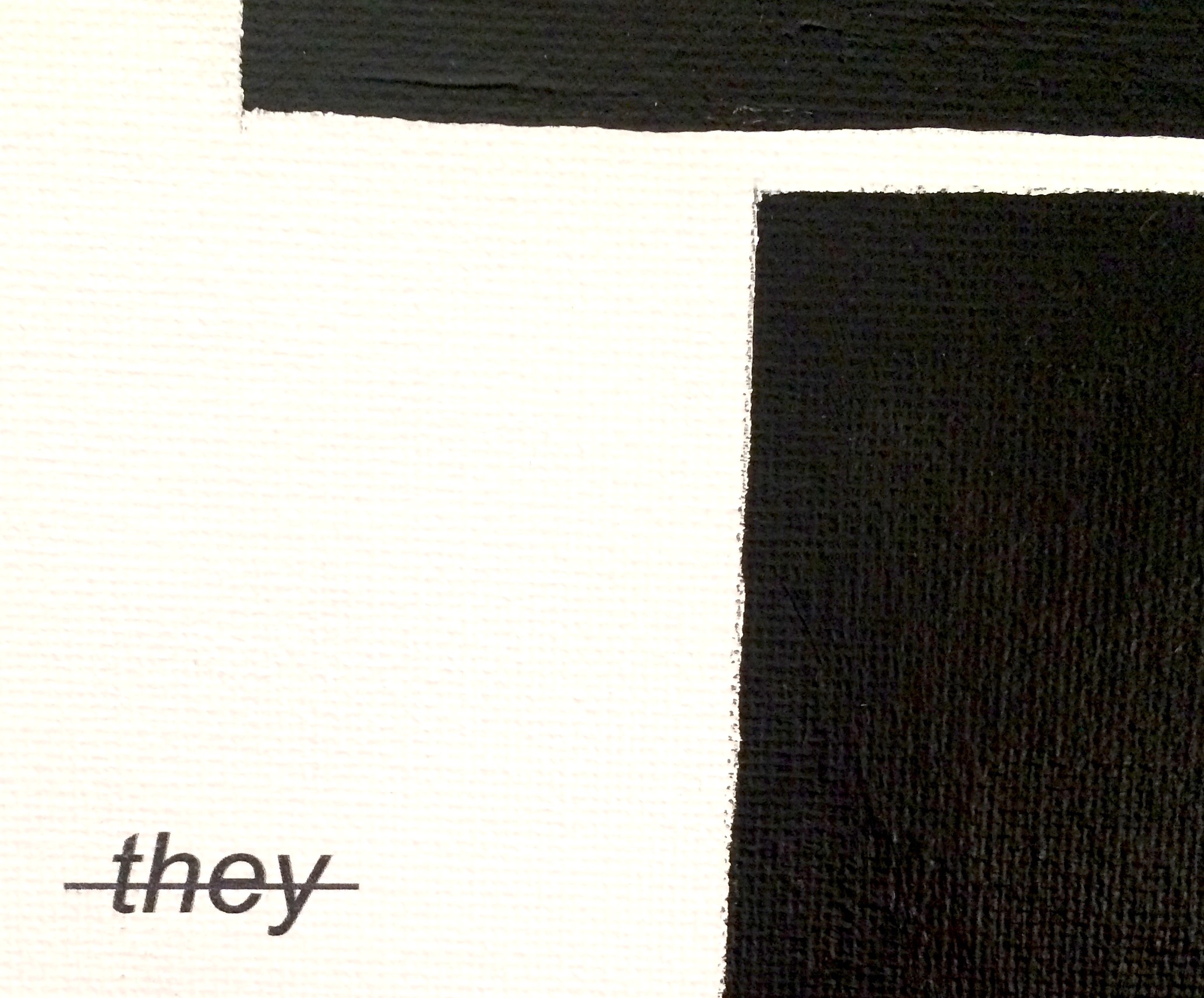

I was asked to produce a work (in PDF) for Week 21 of "52 Weeks," and contributed this painting.

Previously I wrote a book chapter, "'Everything You Can Imagine is Real': Labor, Hype, and the Specter of Progress in Dubai,"†

Yet for the "52 Week" campaign I decided to draw on an older legacy of labor in the service of cultural enterprise. I'm sharing some of those research visuals here.

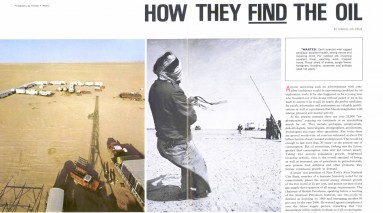

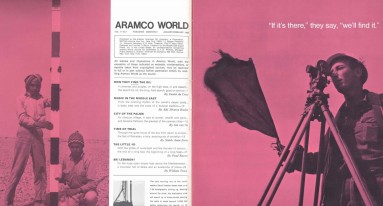

The most arresting precedents came from a 1963 issue of Aramco World Magazine (later, Saudi Aramco World). As historian Robert Vitalis outlines in his crucial America's Kingdom, the settlement operations of the Arabian American Oil Company (the largest U.S. private investment globally) "rested on a set of exclusionary practices and norms that were themselves legacies of earlier mining booms and market formation in the American West and Southwest" (xiii). Vitalis compares this system of neo-imperial enterprise—long mythologized as a generous, less exploitative affair than "British plantations or mining firms in Africa"—to American Jim Crow and South African Apartheid. Arab oil workers, whose names rarely appear alongside their pictures in Saudi Aramco World in contrast to white American or European bosses, were effectively barred from crossing color lines on the compounds, never allowed to live with their families, and banned from contact with Americans. (Americans who made contact with Arab families were deported from the Kingdom.)

These segregation practices led to Saudi worker strikes in 1945 and well into the 1950s, news of which public relations campaigns took successful measures to suppress. Though Saudi Aramco World has been in circulation since 1949, back issues dating prior to 1960 have not been made publicly accessible. One of Vitalis' central arguments is that "firms are a lot like states when it comes to telling their own stories" (11). Consequently, the nature of "economic imperialism" is precisely to peddle company histories like "American exceptionalist fables" (ibid).

The fables of American beneficence, generosity, and heave-ho entrepreneurialism come to life in these archival images. The juxtapositions divulge a racial hierarchy the firm otherwise disguised with its "equal partnership" credo. In the spread background, one finds nameless and unspecified Arab oil workers, long held back from promotion to drilling, engineering, or other high-skilled positions; in the foreground, American urban planners and engineers who are not only named and profiled by professional or personality but endowed with voice-of-God pull-quotes ("It's there," they say, "we'll find it").

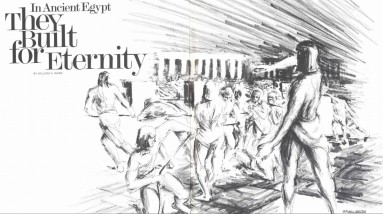

Some full-spread features like "In Ancient Egypt, They Built for Eternity" (from which my piece takes its name) mythologize ceaseless, unified manual labor through Orientalizing fantasies.

Prior to studying Saudi Arabia I had only a sliver of understanding of the history of Arab "coolies" in service to the mythological Saudi-American "special relationship," whereby manufacturing the virtues of duty and citizenship to the firm belied truly sickening racial hierarchies and privileges.

In the course of witnessing firsthand the blatant abuse of worker rights in the U.A.E., I remember being accused (curiously, by a non-Emirati denied citizenship despite living in the Emirates for decades) of airing dirty linens in public. It'll be easy to make the white man hate Arabs, this argument went, as though (a) abuses of South Asian and East Asian temporary workers were merely an "Arab" problem, without intricate layers of American and European complicity and collusion, and (b) revelations of abuse at the hands of U.A.E.-operated firms would ricochet off the gleam of giant towers to form a negative image of Arabs as malignant employers.

Yesteryear's avowed goodness of firms with "special" relationships to Anglo-America parallels with today's avowed goodness of institutions with "special" relationships to art.

I do not think it possible to justly account for contemporary multinational labor exploitation on a grand scale (and Saadiyat Island is a large dot on this grand scale) without addressing far-reaching race- and class-based mythologies that buttress them. These mythologies are not mere "days of yore" historical narratives but living, breathing organisms that threaten to strike out names, faces, strikes, resistances, families, migrations. Between nondescript, colossal blocks of granite.

![[they] built for eternity - gharavi - 2014](https://thenewinquiry.com/app/uploads/2014/03/they-built-for-eternity-gharavi-2014-383x499.jpg)