Today is Elvis Presley's birthday. He would have been 80. Most people accept that he died in 1977, at the age of 42, which means I am older now than he ever was, a fact I have a hard time wrapping my head around.

I'm currently reading Careless Love, the second volume of Peter Guralnick's biography of Elvis, and it is bringing me down. It's about how fame was a collective punishment we administered to Elvis, which he would not survive. Fame allowed him to coast along when he should have been stretching himself; like a gifted child praised too much too soon, it made him incapable of coping with challenges. Fame allowed his manager, Colonel Parker, to construe Elvis's talent as a cash machine. Parker encouraged in Elvis a zero-sum attitude toward his art, so that he demanded as much money he could get for output as superficial as they could make it, as if the shallowness implied savings, a better bargain from the forces who commercialized him. Fame transformed Elvis into a kind of CEO who inhabited his own body as if it were a factory, a capital stock, on which an enormous and ever-mutating staff relied upon for their livelihood. As a consequence, fame isolated him completely. His friends, no matter how much they loved and respected him, remained a paid entourage whom he could never completely believe actually loved him for real. "He constructed a shell to hide his aloneness, and it hardened on his back." Guralnick writes in the introduction. "I know of no sadder story."

I first got into Elvis after stopping at Graceland, his home in Memphis, during my first road trip across the U.S., in 1990. I knew very little about him, just what you sort of absorbed by osmosis from the culture. Elvis impersonators were probably more salient than Elvis himself at that point. My grandmother, I remember, had some of his later records: Moody Blue; Aloha From Hawaii via Satellite. I wanted to stop at Graceland because I thought it would be campy fun; I wanted to re-create the scene in Spinal Tap when they experience "too much fucking perspective" at Elvis's graveside.

But Graceland was surprisingly somber, straddling the line between pathos and bathos, never letting me take comfort in either territory. It didn't seem right to laugh when confronted with the meagerness of the vision of someone who could have had anything but chose Naugahyde, thick shag rugs, and equipping rooms with dueling TV sets. And it was genuinely humbling to recognize the desperation in it all, the dawning sense that Elvis had nowhere to turn for fulfillment and had none of the excuses we have (lack of time and resources, lack of talent) to avoid confronting inescapable dissatisfaction head on.

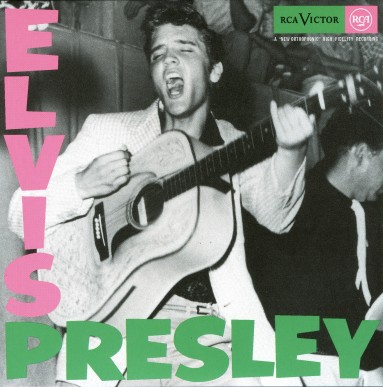

In one of the stores in the plaza of gift shops across the street from Graceland, I bought a TCB baseball hat and cassette of Elvis's first RCA album, the one whose design the Clash mimicked for London Calling.

Every time it was my turn to drive, I put the tape on; listening to "Blue Moon" while driving through the vacuous darkness of Oklahoma was the first time I took Elvis seriously as a performer, the first time I heard something other than my received ideas about him. Then, like a lot of music snobs, I got into the Sun Sessions and the other 1950s stuff and declared the rest of his career irrelevant, without really knowing anything about it. In recent years, I have overcorrected for that and listened mainly to "fat Elvis" — the music he made after the 1968 Comeback. I'm amazed by moments like this, a 1970 performance of "Make the World Go Away." Wearing a ludicrous white high-collar jumpsuit with a mauve crypto-karate belt around his waist, he mumbles a bit, tells a lame joke about Roy Acuff that nobody gets, saunters over the side of the stage to drink a glass of water while the band starts the saccharine melody, then out of nowhere hits you with the first lines, his voice blasting out, drawing from a reserve of power that quickly dissipates. Then he skulks around the stage, visibly antsy, as if trying to evade the obvious relevance of the song's lyrics to his sad, overburdened life.

I never paid any attention to 1960s Elvis, but now, reading through Guralnick's dreary, repetitive accounts of Elvis's month-to-month life in the 1960s, when he flew back and forth mainly between Memphis, Los Angeles, and Las Vegas as he accommodated a relentless film-production schedule — he made 27 movies from 1960 to 1969 — fills me with an urgent desire to somehow redeem this lost era of his career, to study it and find the obscured genius in it, to rescue it through some clever and counterintuitive readings of his films or the dubious songs he recorded for them. I just don't want to believe that Elvis wasted the decade; I don't want to accept that talent can indeed be squandered, that instead it finds perverse ways to express itself even in the grimmest of circumstances. But this was an era when he was cutting material like "No Room to Rhumba in a Sports Car" (Fun in Acapulco), "Yoga Is as Yoga Does" (Easy Come, Easy Go), "Do the Clam" (Girl Happy), "Queenie Wahine's Papaya" (Paradise, Hawaiian Style), and "Song of the Shrimp" (Girls! Girls! Girls!). I'm not sure it's all that helpful to pursue a subversive reading of Clambake. What there is to see in Elvis's movies is doggedly on the surface; as Guralnick makes clear, these films were made by design to defy the possibility of finding depth in them.

At best, a case can be made for appreciating Elvis's sheer professionalism in this era, his refusal to sneer publicly at material far beneath him. Sure, he was on loads of pills, and the epic-scale malignant narcissism of his offscreen behavior was establishing the template for all the coddled superstars to come. But he wasn't a phony. If he was cynical, it was a hypercynicism that consisted of an unflaggingly dedicated passion for going through the motions. Guralnick describes Elvis in some of these films as being little more than movable scenery, a cardboard cutout, but he is a committed cardboard cutout. A bright empty shell with a desultory name and job description (usually race-car driver) attached, Elvis wanders through an endless series of unconvincing backdrops, reflecting back to us the cannibalizing effects of fame, inviting us try to eat the wrapper of the candy we already consumed.