Casual games mirror women’s work, teaching their players that affective labor counts

At the start of Kim Kardashian: Hollywood, you, the player, learn how to fold a shirt. You tap your smartphone’s touchscreen a few times to have the customizable cartoon avatar straighten a clothing display. Kim Kardashian soon appears, heaven-sent, and you’re whisked out of your shabby shop and into her world of fashion and celebrity, where you climb your way toward the status of an A-List star like Kim through a successfully managed in-app career of smiling at the camera and maintaining social ties.

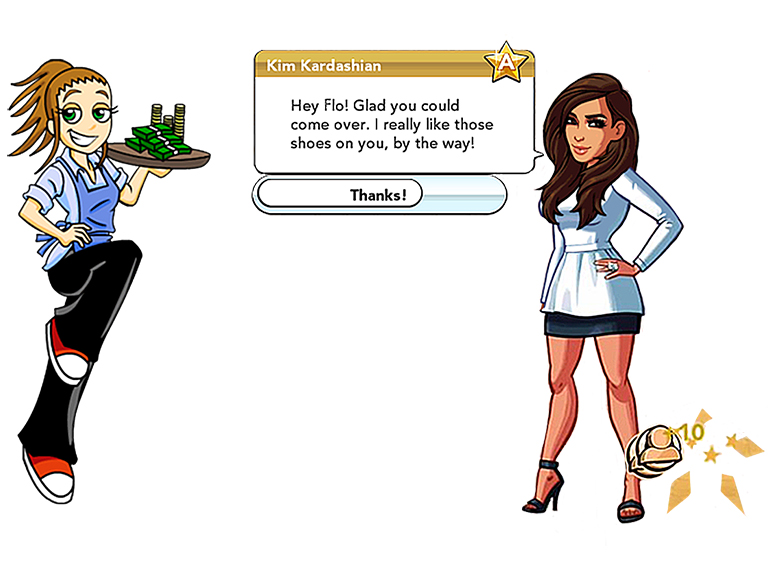

In Diner Dash, a similar tale of rags to riches is set up from the beginning—this time a pre-named avatar, Flo, is unhappy in her bureaucratic office job before deciding to make the leap into small-business entrepreneurship. She opens a diner, which, depending upon her/your waitressing skill, can evolve into an ever-fancier diner through success at serving customers quickly enough to keep them happy. In some versions Flo is eventually awarded transcendence in the form of a third arm. It’s a wry bit of humor from the game: A job well done rewarded with the increased capacity to work.

Both Diner Dash and Kim Kardashian: Hollywood are games where play takes place within the realm of a job—in the service and entertainment industries, respectively—with most of the drudgery, tedium, and frustrations of labor, waged or unwaged, abstracted away. At the center of both games is the management of the emotions of others, a distinctly feminine and post-industrial form of work. This curious conceptual heaviness has been noted: Media theorist Shira Chess writes that Diner Dash “re-enacts complex relationships that many women have with work, leisure, empowerment, and emotions,” and Ruth Curry wrote in Brooklyn Magazine about Kim Kardashian: Hollywood that “Kim Kardashian is what getting paid for ‘women’s’ work looks like.”

While it may appear to be a simple transposition—casual gamers find they enjoy playing in familiar, if fictional, environments—something more complex is taking place. At these moments where our play literally starts to resemble our work, on screens full of red hearts that need tapping and digitally simulated smiling, the player must learn the game’s mechanism to succeed, mastering its demands. Popular games like Diner Dash and Kim Kardashian: Hollywood intervene at a historically decisive moment in the development of labor and leisure, providing a powerful model for quantifying unwaged work. They can offer insight about the potential future of work and play, at borders where the often-porous membrane between the two breaks down.

The intellectual history of affective labor can help us understand the place of emotion in this puzzle. Originally conceptualized in terms of the feminine provision of care—the management of feelings by the mother, the midwife, the nurse—theories of affective labor grew from second-wave socialist feminist analysis, which place it as part of the “invisible labor” of women’s reproductive and domestic work. These accounts were concerned with the relevance—and lack thereof—of domestic work and motherhood to the industrial economy, and ways in which exploitation along gendered divisions of labor became naturalized as part of the female character.

In 1975, Silvia Federici wrote that housework had “been transformed into a natural attribute of our female physique and personality, an internal need, an aspiration, supposedly coming from the depth of our female character.” Federici’s Wages Against Housework is a polemic, and these early conceptualizations of affective labor served as a call-to-arms for housewives to think critically and resist the economic conditions imposed upon them by the nuclear family.

Eight years later, in her book The Managed Heart, sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild theorized the commercialization of emotion by tracing airline employees’ increasing distance from their own feelings. Hochschild’s flight attendants are expected to manufacture a sense of well-being and ease for their passengers (as well as the sense, for some, of being sexually desired) while making the hospitality appear effortless and innate. To reveal that this warmth takes effort—to show struggle or fatigue, to let the labor show in an unseemly way—is to risk damaging the product.

Hochschild recalls Marx’s young factory laborer who works for sixteen hours a day, becoming “an instrument of labor” as he produces wallpaper under brutal conditions. The common ground between the airline attendant and the factory worker is the requirement that they mentally detach themselves from their products, the former from his body and the latter from her emotions. Once this thread is drawn, Marx’s theories of worker exploitation and alienation gain new meaning in relation to Hochschild’s twentieth-century emotional laborers, leading her to ask:

When private capacities for empathy and warmth are put to corporate uses, what happens to the way a person relates to her feelings or to her face? When worked-up warmth becomes an instrument of service work, what can a person learn about herself from her feelings? And when a worker abandons her work smile, what kind of tie remains between her smile and her self?

Hochschild does not offer simple answers to these questions, but her work does bring emotional laborers at risk of becoming estranged from their own affects into the sphere of materialist inquiry on worker alienation and liberation. Echoing Federici but bringing the work of affect into the realm of already-waged labor, Hochschild calls for a reevaluation of which kinds of caring are natural and which are work, what should be done for love and what for profit.

Paralleling the way affective labor troubles traditional boundaries between labor and leisure, Kim Kardashian: Hollywood and Diner Dash make the categories of work and play vulnerable to confusion. Both are casual games, meaning they can be learned in less than a minute, are forgiving of mistakes, are short but highly replayable, and are inexpensive or free. The form is as popular as it is profitable: in 2010, according to the Casual Games Association, the industry had revenues of nearly $6 billion on mobile, iPhone, social networks, PC, Mac, and Xbox platforms and an estimated player base of 200 million. The games are distinguished by low time commitment, easy access, and a return of the video game to mass culture and its origins in the arcades of the early 1980s. Casual games, like affective labor itself, are historically and deliberately coded as feminine in opposition to hardcore games, their masculine counterpart.

By welcoming fragmentary engagement, casual games subtly pervade the lives of their players in the minutes of getting a snack at work or sitting on the bus during a commute. What makes casual games “casual” is the way they fill in the empty spaces of their players’ lives, never capturing an extended period of full attention but also never receding fully into the background of awareness. Aubrey Anable, a visual and cultural studies theorist, places casual games in the history of mass media specifically geared toward women and a life built around domestic labor, with the soap opera being a key example. Both soap operas and casual games are heavily segmented, repetitive, and built to “correlate with women’s work in the home,” Anable argues. Casual games are designed to keep their players continuously engaged without ever becoming too demanding of attention. Infinitely pausable, they are perfect for the mother who must remain attentive to a fitfully crying baby or the hyperemployed worker who must always be available to respond to company demands.

In both Diner Dash and Kim Kardashian: Hollywood, the resources a player must manage are a mix of material (money, furniture, and clothes) and immaterial (energy, happiness, and social or cultural capital). The quantification of these resources—dividing material goods, human health, and affect into similar units—serves to flatten them each into comparable and exchangeable currencies. Both games offer narratives of progress, with gameplay that stays essentially static.

Both games also fall into the category of “time management” games, meaning that many of their mechanics emphasize the use of resources or actions limited or controlled by time. To be asked to manage resources under time restrictions is to feel a sense of urgency mixed with tedium—time management games are inherently tied up with work, a mad hustle alternating with periods of waiting. They emphasize action, reflexes, decision-making, and efficiency. Diner Dash and Kim Kardashian: Hollywood games fill their screens completely, demanding their players’ full attention. Time management games require their players to make both correct choices (being a smart player) and quick choices (being a skilled player).

We lack the vocabulary to identify and analyze things that look like games but aren’t primarily playful. Media theorists have noted this tension in hardcore games; David Golumbia cautions against conflating the form of a game with the action of play, and notes in his analysis of World of Warcraft that the game encourages and necessitates behavior “as repetitive as the most mechanized sorts of employment in ‘the real world’” by letting players specialize in professions such as mining or crafting. Golumbia locates the pleasure of this kind of grinding, repetitive gameplay in the satisfaction of binary task accomplishment, where goals are “well-bounded, easily attainable, and satisfying to achieve, even if the only true outcome of such attainment is the deferred pursuit of additional goals of a similar kind.”

New media scholar Patrick Jagoda observes that to be a player of World of Warcraft “means to be a laborer and a manager,” citing “aspiring to a higher rank, following instructions, engaging in war making, and accumulating private property” as the first skills a player is taught to value in-game, and “team building, managing a guild, and administrating resources” as the habits of successful players. Golumbia writes that these repetitive, goal-oriented games create a managerial class much in the way military simulators create soldiers. He ends on a sinister note:

If they simulate anything directly, that is, games simulate our own relation to capital and to the people who must be exploited and used up for capital to do its work. But it is overly simple to call this activity simulation: a better term might be something like training.

I’d like to propose a similar conclusion for casual games, with a tentative but earnest glimmer of optimism. Games offer a way to simulate and view complex systems from the outside, to pick them up and play with them as a child might play with a toy machine, to understand what they are able to do and where they are broken. The process of coming to understand the levers and gears of a game—what game designer and theorist Ian Bogost calls a game’s “procedural rhetoric”—is an opportunity for cognitive estrangement from familiar systems of labor, a way to understand dynamic networks and nuanced relations with a fresh set of eyes.

Quietly and perhaps unintentionally subversive, Diner Dash and Kim Kardashian: Hollywood approximate a first step toward naming and honoring the processes by which affective labor is extracted from workers. Even in their simplicity and mundanity the games operate as instruction manuals, teaching and training their players how to relate to the emotionally demanding work in their lives. By blurring the boundary between work and play, including the literal quantification of affect in hearts and happiness meters, Kim and Flo teach their players to value immaterial forms of labor alongside the production of objects, feminist work akin to the manifestos and pamphlets that the International Wages for Housework Campaign was spearheading in 1970s Italy.

When Silvia Federici wrote Wages against Housework, she wasn’t calling for hourly wages for housewives as an end in itself, and this is key—she wanted recognition of housework as labor specifically to bring it into the realm of things that can be refused and revolted against. To radically reorganize affection, love, and care in the labor market is no simple task, and Diner Dash and Kim Kardashian: Hollywood certainly offer no solutions. What they do offer is a first suggestion, incredible in its existence on a mass-market scale: to make affective labor count, to think critically about our fraught relationships with our work, and to playfully reimagine what might be.