As part of their early schooling, Indonesians in the Soeharto era were deliberately traumatized by the state

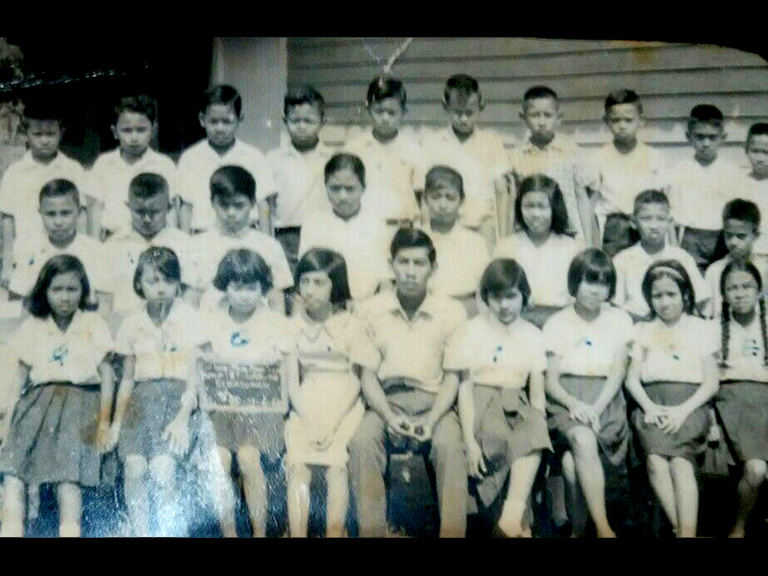

THIS is a photograph of my mother as a schoolgirl in the fourth grade in Jakarta, circa 1965-1966. She is the one with the short bob and mildly petulant facial expression, indicative of a stubborn sulking called mabuduik in her native Padang language; she is in the first row. I received her permission to use this photograph, an immediate yes, after revealing that I was writing a piece about 1965-1966. It’s all I had to say, those numbers in a row.

Simply mentioning “1965” for many Indonesians invokes a deep-rooted anxiety and distress, along with a deeper-rooted wish for catharsis and redemption. The years my mother was nine and ten, anywhere from 500,000 to more than a million people, suspected and actual Indonesian Communist Party members, intellectuals, artists, ethnic Chinese, labor and women’s rights organizers, their families and friends, were killed. Many others were imprisoned, all caught in the choking swirl of local politics and the Cold War. The shape of their descendants’ lives were forever altered, hidden beneath the weight of an ensuing 33 years of propaganda under Soeharto’s New Order government. Whatever Lyndon Johnson knew or didn’t, there was a festooning of violence, sparked by U.S.-backed intention to open up our markets, in a manner it would not be untoward to call the slitting open of a wound.

Today we face a morass of forest fires and haze, mining and overfishing, tourism and deforestation decimating ecosystems from Kalimantan to Bali, where villages quietly harbor mass graves. We are 17,000 islands in a warming sea. The wound was not only left untreated, but also unreported and spoken of surreptitiously, passed off as mere growing pains. “Indonesia is an industrial giant now!” says a Jamaican-born cab driver to me in England 50 years later, “You should be proud.” I remind him of what had occurred to make it that way. “I know,” he says, “That was terrible, terrible. I’m not excusing it. But tell me—when is history ever fair?”

On September 30, 1965, an alleged attempted coup occurred against then-Indonesian President Soekarno. The exact circumstances of this attempted coup are much debated, but were blamed on Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) sympathizers. It resulted in six generals’ bodies in a grave, the overthrowing of Soekarno, and the instatement of President Soeharto. Until he was forced to step down in 1998, when Indonesia became a democracy, the founding mythology of Soeharto’s New Order regime was built on the alleged events of that day. Obscured was the aforementioned massacre of hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of innocent supposed Communist sympathizers, Indonesia’s own Holocaust, never mentioned by state-controlled media—nor school curricula—as anything other than the vanquishing of “godless” adherents to Communism.

For many of us, the acts of September 30, 1965, as told by the state were our first real encounters with excessively violent tales. My own first real understanding of violence as an organizing myth was inextricable from celluloid, sex, and ghosts. This was far from being my childhood experience alone. It is an imprint I share with millions of Indonesians who grew up in the Soeharto era, a psychological imposition I now understand as deliberate traumatization on a mass scale.

In 2015, I have a night terror in London. It is extensive, elaborate. It begins with a drama of suspicion and menace between three people, that ends in a gory car accident in a dark wood, and discovery of the vehicle and its mangled victim in a tree by two quarreling lovers on a motorcycle, corpse blood and bone in the headlights. The arbor’s darkness grows wild, multiplies, and somehow the night reaches over into my room, personified as a dark cloud over my bed, beginning to take indistinct human form and bend over my body. Conscious in this dream, I watch powerlessly as the force proceeds to lick my collarbone. I feel warm saliva on my skin. My arms try to fight off the intrusion and are leaden. My tongue feels weighed and thick, but attempts to scream, and finally, in the middle of the night, steeped in adrenaline and sweat, I struggle awake yelling, “INI SIAPA?” Who is this?

I have continued to think about this night terror in the days that follow, as I think about how violence in the form of physical and psychological intrusions first entered my subconscious, and as I think about how Indonesians of all socioeconomic classes and backgrounds were not spared from the New Order’s inculcation of psychic childhood scars. Scars we never speak of, and perhaps deem unnecessary to discuss, that shape how my generation of Indonesians react to the blows of violence life deals us all in different ways. Scars we diminish and minimize as unimportant, that perhaps still haunt our dreams.

In 1993, I am a fourth-grade schoolgirl in Jakarta. Skinny in a uniform, sulkily mabuduik some of the time, a living version of my mother frozen in that photograph from 28 years prior. School upsets me; we’ve just returned from accompanying my father’s graduate studies in the States, I am still learning to retrill my “r’s”, and though I speak bilingually at home, I somehow can’t figure out what bujur sangkar means (square), failing my first math test. Awkward and book-obsessed, I harbor a real fear of opening my mouth to reveal the flaws I am slowly erasing from my now-muddied Indonesian. This silence is miscontrued as haughtiness, my propensity to go off and write in a notebook alone perceived as standoffish.

It is funny growing up under a free-market dictatorship masked as business as usual. A child cannot be too different, and the education system drills conformity like clockwork. Activist deaths and disappearances and suppression of freedom of speech are not on the news when we come home from school. Families affected by the long shadow of 1965 cannot speak of it, especially those with “Communist sympathizer” lineage. Despite the academic understanding some of us have of Soeharto as a dictator, it still feels funny in my mouth to say “diktator.” Despite the “real history” education at home given by parents who fell in love as student activists, he is for many years just the president. It is generally understood—despite political talk at home and leftist books filling our bookshelves, despite my friends and I not being completely oblivious to the fact that there is a status quo—that it is dangerous to speak against the way things were in public. Most everyone toes the line in public, adults behaving as obedient schoolkids do, quick to ostracize. In middle-class Jakarta, life is supposed to be “normal” and as usual, but there is a tightness in the air.

In tentative ways I begin to try (with low to mixed results) to fit into resumed Jakarta life, returned to after five and a half years. I try to learn the slang of the era, to tighten up proficiency in my mother tongue, and to learn ghost stories. There is a painting of Ade Irma Suryani in the school cooperative, and one day a throng of children at my school clamor loudly to see what is purportedly her image’s ability to look around the room, eyeballs moving to and fro inside the portrait.

Ade Irma had been killed as a five-year-old girl. The daughter of a general, she had been shot by the Communists in the events of September 30, 1965, when they had attempted to kidnap her father. This is common knowledge. I’ve never heard her name before returning to Jakarta. I can’t fit into the school store to see the ghost; masses of small bodies are straining against each other to witness her spirit come back to life.

The spirits of 30 September did come back to life, as it were, with regularity. From 1984 to 1998, the government enforced screenings of a film called “Pengkhianatan G30S/PKI” (“The G30S/PKI Betrayal”) on national television, and in schools, despite the violence. ”G30S PKI” is a work of New Order propaganda extolling the horrors of sadism at the hands of Communists. Communist men were godless traitors who had to be vanquished, and the film supported rumors that Communist women—or Gerwani—were evil villains. From before we could speak to our teenage years, this film was part of the national fabric, and part of the consciousness of my generation.

History books and the film implied Gerwani were hypersexual sadists. To learn the truth about Gerwani was a shock of sadness I still feel viscerally—that an organization of activist women (it was originally “Gerakan Wanita Sadar”, or the Movement of Conscious Women) could be singularly and profoundly portrayed through rumor as cruel murderers. Rumors claimed, and “Pengkhianatan G30S/PKI” did nothing to deny, that Gerwani were murderers who mutilated and played with the six generals’ genitals before and after killing them, before tossing them down that well. Gerwani women had campaigned for women’s and general worker rights, against polygamous, forced and child marriage, wage discrimination on the basis of gender, and Dutch colonialist policies. That the Indonesian women’s movement was so progressive, yet not only stigmatized but also associated with these most heinous acts, remains profoundly important to our generation of feminists and activists, although still so rarely acknowledged.

Back in the New Order decades, the showing of this film on national television and in schools every September 30 was an act of mass historical disinformation manifest as ritual horror show. If I was nine when I first saw images from the film, fingers over my eyes at the fake blood that seemed to pop and ooze from the screen, realistic even in black and white, my classmates had seen it younger. One friend recently told me his parents had forbidden him from watching the film as a child, and this was the first time I’d even heard of such a preemptive policy. Whilst I remember the government censorship agency deeming other films too violent for children to see in the cinema, "G30S PKI" was everywhere, inescapable. Not knowing its content of nightmares was simply impossible. Multiple someones would tell you before you saw it. And you would see it.

The nightmares deployed by the state to disparage anything associated with the Left were both subtle, oblique, and everywhere. So too the traumas of generations before us that are not seen, but accumulate as a patina of anxiety on our lives, passed to us by birth and through being raised by those similarly impacted. Though notable works of literature and art, from once-banned novels to plays and visual art, have more of a foothold nationally and, increasingly, internationally, and though activism has always existed, the government continues to refuse to apologize for ’65, and current state positions are certainly not immune from being held by those with New Order links. Apart from activists, very few spoke of the hundreds of thousands if not millions slaughtered or unlawfully imprisoned, both because many whose families were not directly affected were not informed of them at all, and because of the threat that speaking up held.

Soeharto was ousted in 1998, when my peers and I were teenagers. As we grew into adulthood in fits and starts, so did our fledgling democracy. There would be political assassinations during and after 1998, notably of human rights activists Marsinah, Munir, the disappearance of those such as poet Widji Thukul. What is discussed these days with regards to the events I’ll speak of with the common shorthand of “’65” are policies still lacking with respect to unresolved crimes against humanity, freedom of speech and expression, evidenced by dozens of incidents explicitly reported to local human rights groups of ‘65-linked intimidation, many underreported by the media, the need for truth and reconciliation, and the fundamental need for and difficult separation of New Order elements from the current government. What is rarely spoken of, and is interlinked with all of these, are the less explicit ripple effects of childhood traumatization and conformity.

What happens to a very young brain that has barely understood violence, when they see images and hear tales of wildly, horrifically violent acts that are portrayed as a nation’s founding mythology? What happened to our understandings of women when as children we were fed regular fables of violent sexual crimes—not against women, not thousands of unreported violent and sexual crimes against Gerwani and suspected Gerwani women, but in a terrifying reversal, lies of crimes perpetuated by them against generals? What did it do as small girls and boys to understand the term “mutilated genitals”? What nightmares literal and subdued have we carried with us and never shared with each other?

In the larger-scale talk about “censorship returning to Indonesia,” so little discussion is given to the psychological impact of decades of not only repression, but state education on violence from an early age that is far beyond the generally accepted norms of what should be absorbed in childhood. So little conversation is given to matters not of hard policy, but of these quiet yet palpably strong fears that never left us, whether in our private lives or in our houses of power and national decision making.

Indonesia has been a democracy for 15 years. Its democracy is now an adolescent. What nightmares does an adolescent continue to have, when it experienced deep trauma in infancy, and continues to bear the extended brunt of it? What’s needed is conversation about how these nightmares shift inside us as generations throughout our life cycle, and how it affects how we do our jobs, behave within our families, and heal ourselves and our societies.

There is a direct correlation between the mark of knowing about sexual violence as something “evil Communist women” do, women who were in fact social justice organizers, and the dismissal and outright perpetuation of violence against women in Indonesia, which as it is everywhere is sadly endemic. There is a direct correlation between the association of sex with horrible violence as one of our earliest understandings, and our struggles to include sexual and reproductive health education, including measures to prevent dating and marital violence, in school curricula. I see a deep-seated othering of minorities in destructive ways—with regards to ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, disability, and gender—that comes from our subconscious fear of the consequences of being marked as different that the New Order inculcated and exacerbated in our formative years.

There is also a need for articulating, for bringing to light, and for healing the parts of ourselves that are never spoken of. Things that are normalized or minimized. Memories like watching violence on a television screen as a very young child, and the experience of accepting fearmongering as truth. There is a deep need for holistic mental health improvements in our country, one where therapists and psychiatrists and otherwise-healers, traditional healers, understand what is at stake, understand the history of our nation, and how it is connected to suffering across generations on a biological level—what research scientist Rachel Yehuda calls intergenerational trauma. Such trauma is not only passed on from mother to child, but reinforced through the ways in which parenting affects psychology. There is a deep and systematic ignoring of this impact of the New Order regime in families of origin when it comes to therapeutic care, not to mention the complex ways in which local politics influence well-being, and how these local dynamics were influenced by history.

There are acts of censorship that gain widespread media coverage, but little conversation is given to local government acts that do not, and the even less-publicized, subtler, often everyday forms of community-, peer-, and self-censorship. Even knowing what I do now, it has taken considerable inner work to overcome childhood fears of being attached to certain language and titles, “Gerwani” or “PKI,” that we learned early on would lead to ostracization and punishment.

Artists have been writing and creating about ’65 over the years, and we are nowhere near done with it. Activism has existed in various forms during the New Order era and since, and it still has a ways to go. There are movements, artworks, and simply stories that need wider appreciation, most importantly of all within the country, but alongside and with this cultural production and de-silencing, we need to face up to the fact that we are marked by a form of trauma. So is our parents’ generation. So is our grandparents’ generation. We are all three generations survivors and strugglers, enablers and criminals by various definitions, ordinary people who didn’t ask for harm, who have and are trying to cope the best we can. Our national challenges are enormous, from environmental destruction to education reforms to corruption. Underlying all of these, however, are the psychic barriers we have to break through to make our country better. Behind every policy-making act and gesture of activism are collectives of individual people who need to face up to the truth to move us all forward.

As my peers from elementary school have children, I wonder which of them will perpetuate the inculcation of violent myths that need to be denied, and which will educate in a different way entirely. I wonder which of them have nightmares sometimes, and I want to tell them, if they’re reading, so do I, and I am sorry.