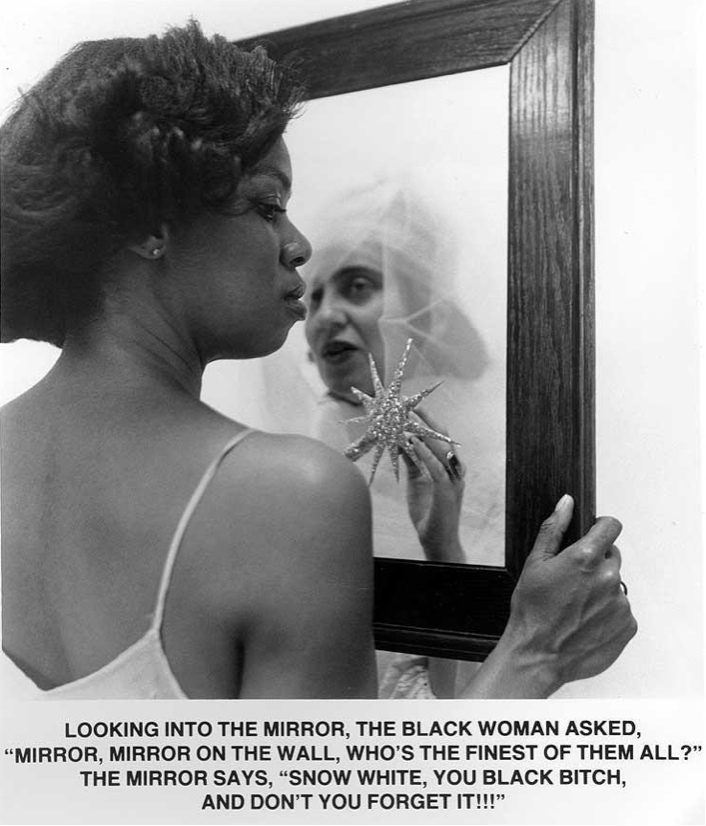

“The black female's body needs less to be rescued from the masculine "gaze" than to be sprung from a historic script surrounding her with signification while at the same time, and not paradoxically, it erases her completely.” —Lorraine O’Grady

MAYBE 2013 felt like the beginning of something; around then we began to hear murmurs at the margins of this idea that the selfie might be powerful. It started with young queers and people of color and a realization that perhaps if you could flood the network with something, it would become impossible to ignore. The selfie soon was written of as a “sign of life” — as the ultimate tactic toward #visibility. As we were taught via the likes of Susan Sontag, “photographs furnish evidence.” The image is, or can be, a powerful verifying tool, and with the selfie it seemed that you could continually verify and affirm your very existence on your own terms.

Time passed and the selfie’s more general life- and difference-affirming politic — which had previously allowed for a wide variety of non-normative identities to circulate and receive validation on user-driven platforms like Tumblr and Instagram — whittled itself down to its most palatable iteration. With aid from online art and culture media platforms, Feminism with a capital F began largely to overtake the other causes that the selfie politic had previously championed. What remains, in 2016, is a political and artistic orientation that revolves primarily around a network of young, female-identifying artists and creative-types for whose work the computer or mobile-device based selfie is the conceptual and formal fulcrum. With the help of platforms like Dazed Digital, Vice, and their lesser cousins, this selfie feminism has taken hold of and become the mainstream.

The nascent selfie politic’s success in making itself visible made it vulnerable to subsumption within already dominant ideologies — which is to say, ideologies that center and favor whiteness. And white feminism, for whom the selfie politic was a wet dream, was first to pick up the scent.

White feminism’s eagerness to appropriate the selfie as political tactic can be attributed to the fact that it seemingly makes good on the manifest destiny of mainstream feminism’s long-running beef with “the male gaze.” In all of its simultaneity, the Internet perhaps allows the bearer-of-the-patriarchal-gaze to look more leeringly, make his pleasure known more audibly and reproduce it with greater ease. In the face of this, the selfie provides opportunities to wrestle narrative power from “man as bearer of the look” and returns it to the "woman"-made-object through continual self-narration and representation. The new selfie feminism thus more or less hastily and anachronistically maps a second wave feminist visual theory — myopically drawn from freshman year gender studies favorite Laura Mulvey and spiced to taste with a Butleresque tendency toward performativity —onto digitally-networked social life and artistic production.

“Whenever you put your body online, in some way you are in conversation with porn.” A quote from artist Ann Hirsch, this sentence was featured as an epigraph on the landing page for the online exhibition Body Anxiety (2014). The show, organized by artists Jennifer Chan and Leah Schraeger, was explicitly concerned with the politics of the gaze online, featuring a roster of artists “who examine gendered embodiment, performance and self-representation on the Internet.” Chan and Schraeger cite art and cinema’s long histories of using “the female body and nude [as] an ongoing subject in male-authored work.” Echoing Mulvey, they write, “more often than not, the woman’s body is capitalized on in these works while their voice is muted.” Other selfie feminists, like those regularly featured on Dazed and Vice such as Alexandra Marzella, Arvida Bystrom, Molly Soda, Audrey Wollen, and Petra Collins, express similar views.

Here there is a shared belief that the control afforded through the act of self-imaging is invaluable; nothing less, in fact, than the primary feminist tool for resistance. The claim follows a logic in which circulation of personal narratives through Instagram and other social media platforms is supposed to provide points of identification for all women, everywhere; and finally, there is a demand for equality; that ‘the female body’ be treated as equal to its male counterpart and for its vulnerability to be without consequence. Arvida Bystrom and Molly Soda both spoke in 2014 on “the female body” online, advocating for body positivity and an end to the inescapable sexualization of the female form. Soda says things like: “Being open with your own body allows, invites and encourages others to do the same or to at least feel good about their bodies.” Bystrom: “A body has to be able to be a body without being sex.”

However digital and radical this brand of feminism is marketed as being, in taking up the mantle of second-wave feminist cinematic and visual theory, selfie feminism most unfortunately takes on its baggage as well. Selfie feminism is guilty of extending the violence and ignorance that plagued its forbears. As bell hooks writes in “Ain’t I a Woman,” white feminism has long suffered from “a narcissism so blinding that [it] will not admit two obvious facts: one, that in a capitalist, racist, imperialist state there is no one social status women share as a collective group and second, that the social status of white women has never been like that of black women and men.” Selfie feminism likewise claims a universal female experience located in "the female body." The artists at the forefront of what the media calls a "movement" and the media itself often fail to note any nuance beyond “female body,” “female form,” “girls,” etc.

As hooks notes, “white racist ideology has allowed white women to assume that the word women is synonymous with white women, for women of other races are perceived as others.” While perhaps unintentional, the functional specificity of "Feminism" — shrouded as it is in centuries of totalizing language, becomes exclusionary to non-white women — as well as trans, nonbinary, and disabled people. It is this that allows Chan and Schraeger to place Hirsch’s quote at the forefront of their exhibition without further interrogation of whose bodies are entailed, and "what kind of conversation with pornography?" It is this that allows Bystrom to advocate for "equality" in the way that we consume bodies. And it is this that allows someone like Molly Soda to make the claim that her work encourages body positivity. But the people who look like Molly Soda — and who might be affirmed by her images — are likely to be other young, able-bodied, white-presenting, cisgendered women.

LOOKING at exhibitions like Body Anxiety as well as the many articles featuring artists of the selfie feminist persuasion, one might think that Black women and femmes had never touched an iPhone or a Macbook. Body Anxiety features 21 artists and only two of them are Black. And of those two Black artists, the wonderful Rafia S. and Hannah Black, only Rafia includes work that engages anything remotely similar to selfies. Hannah Black’s work, on the other hand, appears decidedly anti-representational. Interviewed about the piece, titled My Bodies, she identifies it as a gesture toward ongoing Black feminist critiques of white feminism’s assumption that “all women have bodies in the same way.” Further, the work references the ongoing question of “to what extent white thought is able to conceptualize Black people as having bodily integrity.”

Considering this alongside the fact that we are still mired in a battle that traverses screens and streets to assert the value of our very particularly Black lives and bodies, it is clear that we cannot apply the same structures of gender and representational politics to the situation of the body that is marked both Black and female. If feminism in the mainstream remains obsessed with male/female interaction — and if by male/female we are really talking about a pseudo-universal framework well-practiced in masking the fact that its true interest is in the binaristic relationship between cisgendered white men and cisgendered white women, the question is: does selfie feminism hold anything of value for Black women at all?

Intuitively, the selfie still feels valuable, but the compounded male, white, and colonialist gazes that work so hard to blur Black women and femmes into oblivion have too much force behind them to leave me with enough agency both to politicize a topless mirror selfie and to believe in that politicization one-hundred percent. Since it has been made abundantly clear, of late, that photo or video documentation proves very little and changes even less, simply documenting the Black female body falls short. Maybe a selfie comes close to proving that you exist – that you are at least firmly situated in time and space — but it proves nothing else conclusive about you: this is to say that, self-documentation of Black life still seems unable to contend with the “mass of images” produced by anti-blackness's aggressive and distributed media campaign.

Merely presenting an image of a Black woman, no matter how affirmative and positive that image is intended to be, might still serve to reproduce an imbalance in agency. Last year’s abuses of Nicki Minaj’s wax figurine at Madame Tussaud's are a charming offline reminder of this. Sure, we can all join in celebrating Nicki, but let us not forget that she is a body, she is flesh, and she is yours to possess. Or as Rozsa Farkas noted in "Whose Bodies 2," “there are hierarchies that are afforded to certain (female) bodies, degrees of agency in one’s self-representation.” Her words call to mind a statement from early Black feminist activist Anna Cooper: “the white woman [can] at least plead her own emancipation.” The black woman, on the other hand, has largely been expected to bear the multiple scars of racism and misogyny — misogynoir — in silence. And among these scars is an objectification that surpasses the image of the body, treading over it and into the realm of sheer, unprotected flesh.

THE Internet already flattens subjectivities into networks of branded associations and metadata. Mental and social operations are concretized and subjects are made objects in a platform-based social world. In this schema, it is perhaps inadvisable for those of us whose subjectivities have not yet been recognized on a large scale to objectify ourselves further using the tools vetted by those who perpetuate our oppression to begin with — even in efforts toward documenting one’s life with the hope of subverting external expectations. And anyway, on the Internet, this subversion is hardly revolutionary work. In fact, the algorithm thanks you for your contribution.

I don’t intend to advocate for a politic of anti-representation or a fundamental refusal of the image. However, being of the mind that to be Black in particular is to be at once surveilled and in the shadows, hypervisible and invisible, an either/or theory of representation seems unhelpful. So long as the feminist politic with the most traction enjoys this uncomplicated relationship to visibility, it will only sink further into aestheticization and depoliticization. As long as its framework is derived primarily from its racist, classist, capitalist “lean-in” equality-core (#freethenipple) predecessor, we – specifically Black women, but also perhaps all of us here whose bodies and selves are failed by a second-wave capitalist, classist, racist, cissexist, ableist feminism — do ourselves a disservice by considering it in the least bit viable.

Rather, we must devise a new politic of looking and being looked at. At the risk of sounding instrumentalizing, something like the Du Boisian double consciousness that has characterized Black life for centuries has wriggled its way into the minds of all subjects and now every single networked human being now exists under this condition of “looking at oneself through the eyes of others” or living, watching, being watched, watching yourself watch others. What could be a workable theory of auto-expression that takes into account the temporally, spatially, experientially flattened act of looking and being looked at? We are each the constant voyeuristic subject and object, both surveilled and surveyor. Devising a theory, politic, praxis (or whatever) that finds its center in the experiences of the Black femme and female body — perhaps historically the blurriest situation one can imagine for a body — might lead us to a theory, politic, praxis (or whatever) that speaks more accurately to the increasingly alienated experiences of all users – in particular those whose gender expressions fall outside of white cis-masculinity. Or as O’Grady writes, “if the female body in the West is obverse and reverse, it will not be seen in its integrity—neither side will know itself—until the not-white body has mirrored herself fully."

DURING the process of writing this I came across images from Adrian Piper’s Food for the Spirit. The photographs document a ‘private performance’ where Piper fasted and read Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason in her NYC loft for an extended period. I tried and tried to make this work the centerpiece of this writing. It felt forced; I generally hate a cheeky art historical retrieval to begin with. However, Piper’s work still leaves me with a deep feeling of its value and its presence is instructive in this attempt toward understanding things a little better.

In the work, Piper looks and demands to be looked at in a most specific way; she is both the black female body in the frame and the maker of the picture at once. Lorraine O’Grady calls it “the catalytic moment for the subjective black nude.” In her total nudity — stripped down in more ways than one — Piper enacts a politic of looking wherein her direct gaze (bouncing around the frame in a near-closed loop) triangulates between eye mirror and lens while we, the audience, view her as though from the other side of a one way mirror. Looking at Piper looking at herself, one becomes aware of the rarity of the moment. Where else, particularly within art history, do we see black women looking straight at themselves and making that looking public? Or as Lorraine O’Grady asks in Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity:

When [...] do we start to see images of the black female body by black women made as acts of auto-expression, the discrete stage that must immediately precede or occur simultaneously with acts of auto-critique? When, in other words, does the present begin?

Piper looks at herself looking, takes herself in as spectator and subject, subject and object at once. It is in these closed loops that O’Grady’s present begins.

To consider the specificities of our experiences as black women — the surveillance and ghostly or bodily violences in our histories, our constantly shifting orientations and centers — and really considering them for what they are without whiteness looking over our shoulders — these are the current tasks at hand. O’Grady writes: “To name ourselves rather than be named we must first see ourselves.” Artists like E. Jane and Shawné Michaelain Holloway pick up where Piper leaves off in Food for the Spirit and where O’Grady leaves the door cracked open in Olympia’s Maid. These artists, among numerous others, approach the ruins of the selfie politic with a critical edge that perhaps only black women, femmes, and gender-nonconforming people can bring to it. E. Jane wrote in 2015, “None of this is as simple as “identity and representation” outside of the colonial gaze. I reject the colonial gaze as the primary gaze. I am outside of it in the land of NOPE.” The “land of NOPE” might be the same realm that Adrian Piper inhabits alone in her apartment, reciting Kant. It could be the site of Lorna Simpson’s figures who refuse and ignore their audience. More recently, it is in the damp cave of Hannah Black’s My Bodies, and it is equally present in the self-sexualization of Shawné Michaelain Holloway.

When it comes to Feminism as a movement, our paperwork has been “in process” for over two hundred years. And in those two hundred years, black women have taken it upon themselves to craft and circulate alternative texts, leaving behind the limiting frameworks of white, middle class feminists. The selfie seems to provide yet another site for this sort of work, the same sort of work that O’Grady and bell hooks endorse.

Reclaimed from the mainstream, the selfie might look something like E. Jane’s “land of NOPE” In this land of NOPE, there is refusal, there is an oppositional gaze, there is multiplicitous sexuality, there is desire, there is protection. Rozsa Farkas wrote:

The act of reclaiming agency over one’s body – of having control over its image – is not only a well trodden ground, but also exists in a society where that act (both in art and in general culture) has not demolished the gaze. The body needs to do more than simply present itself; it needs to insert itself.

Making one’s subjectivity visible, or affirming one’s existence through a selfie has yet to “demolish the gaze.” We must be well aware that the Internet is arguably – at least in American and much of the Anglophone west — dominated by a a mucky sphere saturated with subjectivities flowing amidst and rubbing up against each other, all stark naked. In 2016, catapulting our selves into circulation as image-fragments no longer makes for a resistance or revolution. What happens next is O’Grady’s present in which auto-expression and auto-critique are joined. Perhaps using tools like the selfie in ways that refuse, refute, and redirect, saying “NOPE” to dominant ideologies, and “bye” to a basic-bitch politic of visibility.