In art that defines itself by what it withholds from public view lies the challenge for us to do the same

AN image that is not shared publicly on social media platforms, a dignity image provides the means by which Internet users may gain some measure of control over their increasingly mediated identities online. The act of creating and modifying online identities by deciding which images to share is also an act of erecting boundaries between self-conception and assimilation to an avatar. Avatars are vulnerable to exploitation by social media platforms.

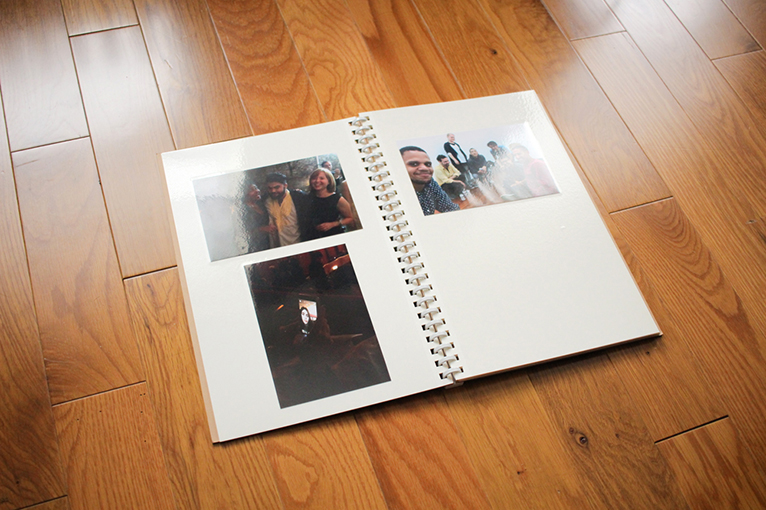

An inevitable reaction to a climate of hyperconnectivity, dignity images are never deliberately identified because they are considered worthless under conditions of capitalist market relations. Identifying them assigns value and authenticity to them. The images withheld from circulation on social media -- whether out of shame, security concerns, sentimentality, financial viability, or convenience -- may be put to use in recovering one’s dignity, or political autonomy, online.

The state exerts no control of the Internet; it leaves this to corporations. Users may form a community as long as they obey the platform’s terms and conditions. Login credentials are the key to citizenship. By refusing to contribute images, users decrease the degree of control over them enjoyed by Facebook, Instagram, and other social media platforms. And this threatens those platforms’ continued viability. Limiting the influence of such institutions can create a less hegemonic Internet space. By refusing to share images, users signal that they want to have control over the content they produce.

Social media promotes a seductive, yet ultimately spurious, intimacy-at-a-distance. Images of objects of admiration and loved ones are plainly out of reach and yet close enough to encourage continued engagement with the platform. Half a century ago, French Situationist theorist Guy Debord predicted the ways in which labor, time, identities, and affections would be exploited by visual and communicative systems. He wrote that these would become grist for representations alienated from the lived contexts of individuals, that is, “spectacle.” Social media -- Facebook, particularly -- is, then, a form of spectacle for the digital age.

Like its competitor Google, Facebook is a company that aims to be a central Internet institution for the various forms of exchange -- cultural, financial, social, and so on. The desire for ubiquity and utility is reflected in such projects as Oculus VR, a virtual reality project acquired by Facebook in 2014; a human-aided AI messenger assistant named M; and an international platform called Internet.org, which aims to provide Web access to the developing world by way of proprietary satellites.

The imperial nature of Internet corporations’ business strategies is rarely grasped in its full effect. Active campaigners for net neutrality aside, individuals may impute benevolent intent to the global presence of Facebook and companies like it. To consumers raised under neoliberalism, a company’s size is an indication of its trustworthiness. Too habituated to be critical, they become lax in their politics and behavior, rarely challenging the ethics of companies they are loyal to and remaining logged in. The dignity image poses an alternative to this habituation. By declaring dignity images in one’s life -- images that won’t be shared on social media -- a user reclaims autonomy from social media platforms.

Unfortunately, the extent to which one becomes conditioned by social media use is not always easy to perceive. When Facebook’s algorithm echoes previous content in later curated posts, the user must distinguish an authentic self from an essentialized self whose existence owes mostly to Facebook’s curatorial algorithms. Self-perception is deeply informed by the content displayed to users by Facebook. In a sense this content mirrors users’ behavior, and the projected self-image desired rests on tracked behavioral data. The effect is that of “autocannibalism,” a term coined by new-media pundit Rob Horning which describes users’ act of consuming their feed. Autocannibalism, he writes, “can create a hermetic feedback loop, where past actions fully dictate future potentialities, foreclosing the possibility of surprise or change. That is part of the pleasure Facebook brings.” This self-consumption forms an image in users’ mind that they will strive unwittingly to actualize through future shares, likes, and perhaps even personal lived interactions and self-expressions. As a result, users’ identities become shaped by the social media platforms they participate in. A remedy for autocannibalism can be found in the dignity image. Deliberately withheld from social media, dignity images provide an escape from the hermetic feedback loop that Horning describes.

The feeling of assimilation by social media can prompt impulsive behavior in users. Use of Facebook, Instagram, and other popular social media platforms becomes compulsory. Left feeling that they are incapable of leaving the sites, some users act rashly by deactivating or deleting their profiles. Rebellion of this kind may be understood as occurring during a moment of clarity, a moment in which the immensity and autonomy of companies like Facebook are felt even if they are not fully recognized. Media theorist Laura Portwood-Stacer refers to such rebellion as “social media refusal,” or “opting out.”

Social media refusal occurs when a user ceases to provide content for a platform. The power of refusal lies in the lack of contributions from the user. As Portwood-Stacer points out, “it is only in comparison with the normalcy of use that non-use has social and political significance.” Because a fundamental component of social media content is shared images, social media refusal relies on the declaration of dignity images by a former user.

The possibility or impossibility of social media is an aspect of the post-Internet condition, a time in which Web use is at once ordinary, humdrum, and utterly necessary. In “The Image Object Post-Internet,” author Artie Vierkant writes that the post-Internet condition is characterized by “ubiquitous authorship, the development of attention as currency, the collapse of physical space in networked culture, and the infinite reproducibility and mutability of digital materials.” It is a time in which all consumers are producers, things “liked” may immediately be monetized, no one is out of reach, and nothing is unique. To Vierkant’s description of the post-Internet condition artist Sterling Crispin has added the further qualities of excessive irony, novelty, persona as product, and the embrace of the spectacle. Though the intention behind social media is the connection of all the world’s individuals, it merely creates an alienating and distant copy of reality to be skimmed and scanned.

Images not shared on social media are often poor instances of the commercial quality expected from content posted on social media. Incidentally, dignity images, which are often less glossy or appealing, end up being images that more accurately represent users lived contexts. We can experience authenticity by identifying dignity images which then become freed from the commercial standards imposed on content that is shared on social media.

In order to remedy the post-Internet condition, Crispin proposes that Web users “more fully embrace directness, earnestness and sincerity. This applies to not only what we make and do, but what we support indirectly through our actions.” Critical points made by Debord he presents as fitting responses to bleak truths. “The immense accumulation of spectacles is not life,” Crispin writes. “Mere appearance is the negation of life and must be inverted into the real. The totalitarian management of the conditions of existence must be abolished.” If social media platforms can be considered managers of conditions of existence online, users’ choice to declare dignity images is a counteraction that allows them to embrace sincerity in the way that Crispin imagines.

In "The Secrets of Surveillance Capitalism," author Shoshanna Zuboff follows Hannah Arendt in advocating replacement of inalienable human rights with an idea of human dignity. Arendt saw an argument for inalienable human rights as resting on a basic level of citizenship; in order to have them individuals must have a place within a state. If they have no place, they become “worldless.” Dignity, on the other hand, is something owed to all individuals, even if they are without a place. On the Internet, social media platforms act as a surrogate for the state, offering citizenship in the form of access to simple and attractive content-sharing platforms. Individuals operating outside of social media platforms are essentially worldless. The dignity image is a means of recovering dignity outside of social media by acknowledging that images outside of these platforms are equally if not more valuable.

Dignity in the post-Internet era must include defense of individuals for reasons other than their effectiveness as an image and product, namely, the value of users’ data trails and shared content to social media companies and their clients. Yet such a defense is hard to envision, because most users would have trouble imagining an Internet without Google, YouTube, Facebook, Amazon, and other familiar platforms, which have trained them to display themselves and evaluate other users displays as spectacle. If there is anything to see in a dignity image it is the place where value lies outside of spectacle. When an image is deemed unfit to share because it does not maintain the standards and motives of other shared content, there arises the question as to whether it is the image that is obsolete or the platform.