“The only one to fix the infrastructure of our country is me—roads, airports, bridges. I know how to build” —@RealDonaldTrump, May 2015

THE master architect of Hitler’s infrastructural plans was Albert Speer, whose megalomaniacal designs caught Hitler’s approving eye. As the war went on, Speer took on greater and greater responsibilities within the Reich. By 1943 he was in charge of coordinating industrial, building, and transport ministries for both military activities and peacetime.

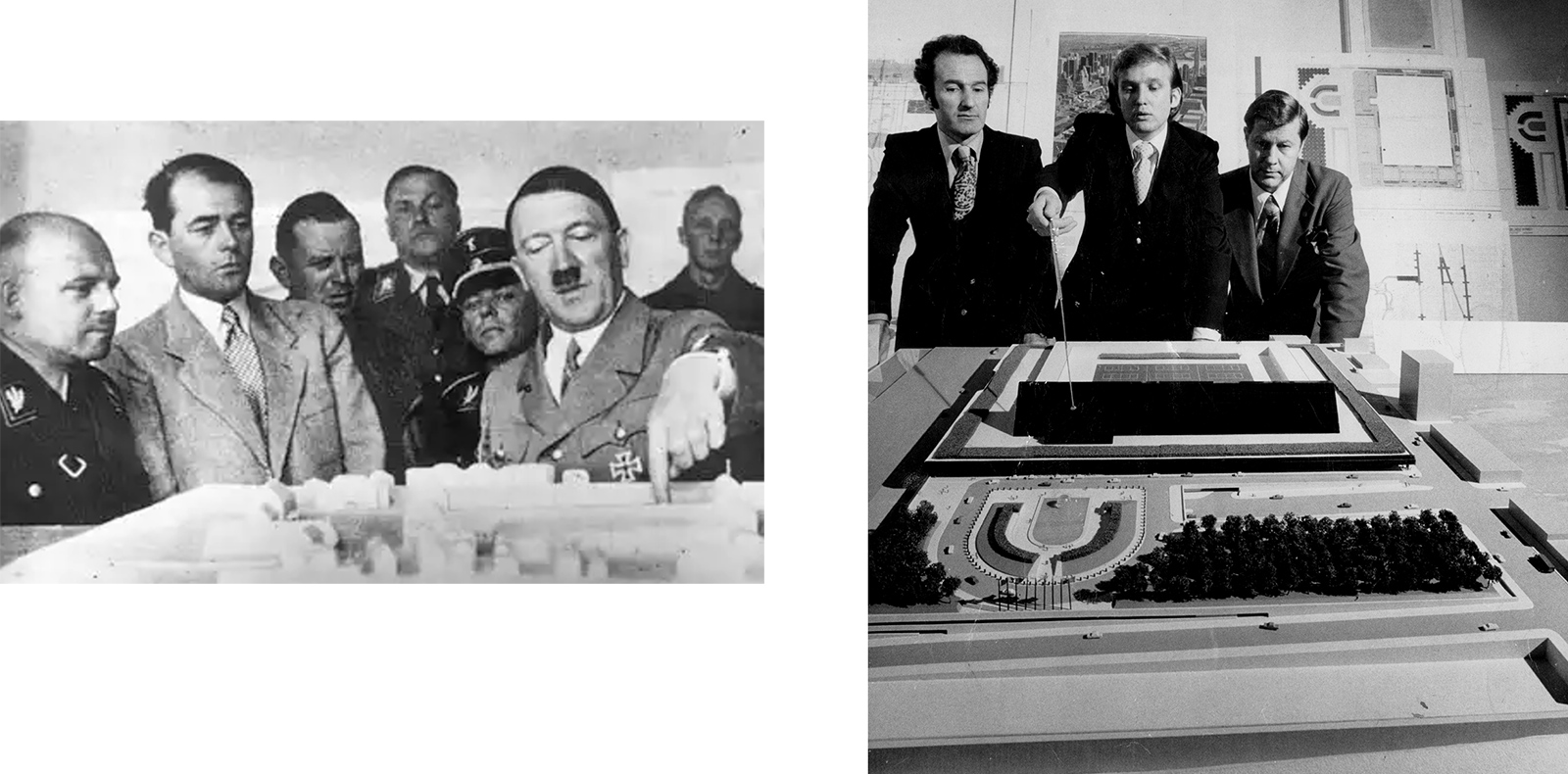

Countless German newspapers printed photographs of Hitler and Speer, before the Second World War, gazing approvingly at their small models for the New Berlin--rectangular wood buildings flanked with exaggerated columns and Swastika-bearing eagles painstakingly painted in red and black.

Speer was given the liberty to create a Gesamtkunstwerk, a “total art work.” Perhaps this was because the realm of the miniature is one of the few scales in which such totality seems possible. “A world at my feet,” Speer later recalled, “who would not have felt dizzy at the thought?” Although nearly all of his designs remained stunted in their model form, his visions were expansive.

As a virtually boundless visual technology, the scale model was the first canvas upon which Hitler tested his radical and military restructuring of Germany. His model city seemed to represent the Reich’s ideal of Lebenstraum, “the need for more living space,” in its purest form: calm, unpeopled, infinite. Hitler liked to say that the purpose of Nazi architecture was to project his rule across the ages. “Ultimately, all that remained to remind men of the great epochs of history was their monumental architecture,” he told Speer. “What had remained of the emperors of Rome? What would still bear witness to them today, if their buildings had not survived?”

No doubt, because of the exaggerated historical importance he attributed to his model city, Hitler was touchy, secretive, and insecure about his plans. No one was allowed to inspect the blueprints and tiny buildings--housed in the vacated former exhibition rooms of the Berlin Academy of Arts--without Hitler’s explicit permission. He even installed a secret tunnel to be able to visit his imaginary city without any interruptions. Occasionally after dinner parties, when he was in a light mood, or on a whim, Hitler would invite guests to see his New Berlin. Guided by his flashlight and the jangle of his keys, supper guests would follow him on his secret path, where, with spotlights illuminating the small models and his eyes flashing with excitement, Hitler would explain his plans in vivid detail.

One picture taken on the occasion of Hitler’s 50th birthday shows him examining, with keen pleasure, Speer’s gift: a model of the oversized triumphal arch. A few months after the photograph was taken, the Second World War began.

As he became increasingly plagued with bad news from the Russian front, Hitler used Speer’s model city as a retreat. He would spend hours there, bending over to imagine himself strolling as a traveler on his grand boulevard, gazing lovingly at his imperial capital. Occasionally, he became so overwhelmed by the sight of his tiny Empire that he would weep with joy.

On these regular visits, he would always pay special attention to the city’s main artery: a grand boulevard, modeled on a scale of 1:1000. Speer conceived of the long avenue, which ran on for nearly 100 feet in the former exhibition halls, as one “continuous sales display.” Like the window of a train, or the panoramic array at a department store, the “German goods” that lined the street “would exert a special attraction upon foreigners.”

Hitler loved to “enter his avenue.” He would bend down, nearly on his knees, and place his eye no more than an inch above the model so that he could admire his city from a proper onanistic perspective--imagining himself as a foreigner awestruck by his omnipotence.

According to Speer, Hitler always spoke from this crouched height with an uncharacteristic liveliness; his usually stiff body loosened. It was, it seems, a type of therapy to imagine himself in this future tense of realized conquest. “In no other situation,” Speer recalled of these situations, “did I see him so lively, so spontaneous, so relaxed.”

Years later, after his release from prison, Speer had a change of heart toward his elaborate life’s work. In an instant, he said, he realized what he had “been blind to for years.” His perfect model--perfect for its exact proportion and tyrannical view--did not make the ideal city. Following the fall of the Reich, the uniform height of the buildings sickened him, and even the varied parts of his grand avenue struck him as “lifeless.” “Nowadays,” he said, “when I leaf through the numerous photos of models of our one-time grand boulevard, I see that it would have turned out not only crazy, but also boring.”

Speer wondered whether “the cruel element in this architecture” was its scale. “Perhaps it was less their size,” he wrote, “than the way they violated the human scale that made them abnormal.” Hitler’s desire to compare himself to other nations based on his enlarged architectural prowess was pathological, as though the express purpose of building anything at all was simply to exceed, in sheer size, the treasures of other nations. His assembly hall was modeled after the Pantheon in Rome so that its oculus (152 feet) would have swallowed the entire pantheon (142 feet) whole. The interior, Speer had calculated, would have been 16 times the volume of St. Peter’s Basilica and could have also contained the Capitol building in Washington, D.C.

In hindsight, the irony latent in such an immense, unreasonable scale was not lost from Speer. Dwarfed by such large buildings, humans themselves became insignificant. In the capacious People’s Hall, designed to fit mass demonstrations of nearly a quarter of a million people, even Hitler himself on his grand balcony would have “dwindled to an optical zero” (zu einem optischen Nichts). Speer realized that these buildings would not only have been larger than other nationalist monuments, but effectively überdimensional, beyond all dimension. The panoptic, panoramic, megalomaniacal perspective diminished, paradoxically, man as the measure of all things. Even as an unfinished project, Hitler’s miniature architecture constituted a sort of world domination; a complete attempt to shrink the people, the nations, and the powers that surrounded him.

In retrospect, it’s clear that these totalitarian scale models never needed to be life-sized. They were already in themselves, Speer reflected, “the very expression of a tyranny.”