The last person to be sentenced was a young woman, Ms. Galvez.

All the other women and men had been escorted, in handcuffs, waist chains, and leg shackles, out of the courtroom. The door through which they disappeared stood open, permitting a view of a monochrome wall. There were no shadows, no movement. No sound came through the door. Thirty-three women and men, mostly men, had disappeared into the halls of the courthouse. Ms. Galvez would be joining them in that silence. She was the 34th and final. It was the first Friday in February, though it could have been any weekday of any month. Operation Streamline, in which immigrants convicted of re-entering the United States without authorization are prosecuted en masse, has taken place every weekday at one-thirty in the afternoon in Tucson, Arizona, since 2008.

After Ms. Galvez disappeared, the magistrate judge took off his black robe, approached the gallery, and without provocation (because no one asked) insisted: These are not mass deportations. Nor is this mass prosecution. He was referring, first, to the fact that his court, a criminal court, does not technically deport people—that is the job of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)—and, second, that until recently the immigrants who stood before the judge, 30 to 75 at a time—based on the court’s cell capacity—were prosecuted at once. Human rights organizations—including the End Streamline Coalition and La Coalición de Derechos Humanos, both in Tucson—have demanded an end to Operation Streamline. The court has responded with a stopgap: Divide the immigrants into smaller groups of five or six, so as to relieve the appearance of mass prosecution. To streamline, in other words, is not a matter of substance but of optics.

Operation Streamline was initiated in Del Rio, Texas, in 2005. It was designed to deter unauthorized border re-entries while circumventing an overburdened civil immigration system, but its actual objective is singular: to criminalize undocumented immigration. Whereas before, immigrants were sent to immigration court, which handles deportation cases, or repatriated, without criminal charges, Streamline processes immigrants through the criminal justice system. In other words, Streamline conceives of and renders undocumented immigrants, regardless of whether or not they have a prior record, as criminals. It was signed into law by Michael Chertoff, Secretary of Homeland Security under George W. Bush, and expanded to Yuma, Arizona, in 2006; Laredo, Texas, in 2007; and Tucson, Arizona, in 2008. It was further expanded under Obama, including into New Mexico, though its main border sectors remain Del Rio, Laredo, and Tucson.

Throughout the Streamline proceedings, Ms. Galvez sat with the other women (four, including Ms. Galvez) at the back of the courtroom. The 30 men sat in rows directly in front of the judge. All but one wore headsets. The proceedings were translated for them into Spanish by an interpreter who sat to the judge’s right. The judge was white and looked bored. Everyone in the courtroom who was not in chains looked bored; some looked in limbo, like reptiles sunning themselves on the lip of a slowly evaporating pond.

Boredom is the expression of bureaucracy. The expression masks the horrors for which bureaucracy works. It was impossible to discern intentions, on the faces of the court-appointed lawyers, good or ill. There were almost as many lawyers in the room as defendants, and almost all of the lawyers were Latino. An enormous seal hung like a primogenital coin on the wall above the judge’s head.

A representative from the Mexican consulate had met with the immigrants, detained down the hall in cells in the U.S. Marshal’s office, that morning. The representative asked about their health, explained to them the process for reclaiming their confiscated possessions, collected information for notifying their relatives (to circumvent, as the consulate said, extortion calls), and asked if they had been abused in any way by Border Patrol or in U.S. Marshal custody.

The immigrants had been strip-searched upon entering the courthouse and would be strip-searched again, twelve hours later, upon entering detention. Their handcuffs, waist chains, and leg shackles were tight enough to make it difficult to walk and almost impossible to go to the bathroom.

Ms. Galvez was in her late twenties. Her lawyer, a Latino man in his sixties, stood over her shoulder. They had met for the first time that morning. He was not given much time to explain to Ms. Galvez her situation and how she was going to plead: barely enough to satisfy the apparently elastic definition of due process. According to "In Harm's Way," a report published in 2015 by the Journal on Migration and Human Security, over half of immigrants prosecuted through Streamline stated that their lawyers simply informed them that they needed to sign their order of removal and plead guilty, while 6 percent stated that their lawyers did not tell them anything. Ms. Galvez would plead guilty to the felony offense of unauthorized re-entry. It was not Ms. Galvez’s first time entering the United States, nor was it for any of the other women and men. Many who are prosecuted for unauthorized entry and/or re-entry not only have family in the United States but have lived and worked here, some for many years.

The first time a person is caught entering the United States without authorization is a petty offense, which comes with a six-month maximum prison sentence. The second time a person is caught is a felony, which comes with a prison sentence from 2 to 20 years and a fine of $5,000. The terms of the plea go as follows: If the person pleads guilty to the felony offense, the felony will be commuted to a petty offense. The person will be sentenced from 30 to 180 days, depending on whether or not they have a criminal record (most do not) and held in a detention center (the Central Arizona Detention Center in Florence, for example, run by the Corrections Corporation of America), after which they will be turned over to ICE.

But the word “plea” is largely rhetorical. As Isabel Garcia—former Pima County legal defender and co-chair of Derechos Humanos—has explained, Plea bargaining is supposed to be a negotiation, but the sentence is predetermined by prosecutors before a defendant enters the courtroom.

Each group of five or six immigrants faced the same line of questions from the judge, who cautioned, in advance, that his questions were going to become repetitive.

Do you understand the rights you are giving up, the consequences of pleading guilty, and the terms of your plea agreement? That was all one question. All 34 women and men stood before microphones. Their lawyers stood very close behind them. The microphones picked up the edges of the lawyers’ breathing. The voices of the women and men were soft, some barely audible. One man answered in English, which surprised the judge; he asked the man to repeat what he said, as if it took him a moment to comprehend how the man could have answered in any language other than Spanish.

Are you pleading guilty of your own free will? Are you a citizen of the United States? Free will sounded perverted and absurd. The fact, or even prospect, of being a citizen of the United States sounded in that moment like a pyrrhic reward for the ruins of what it was won against.

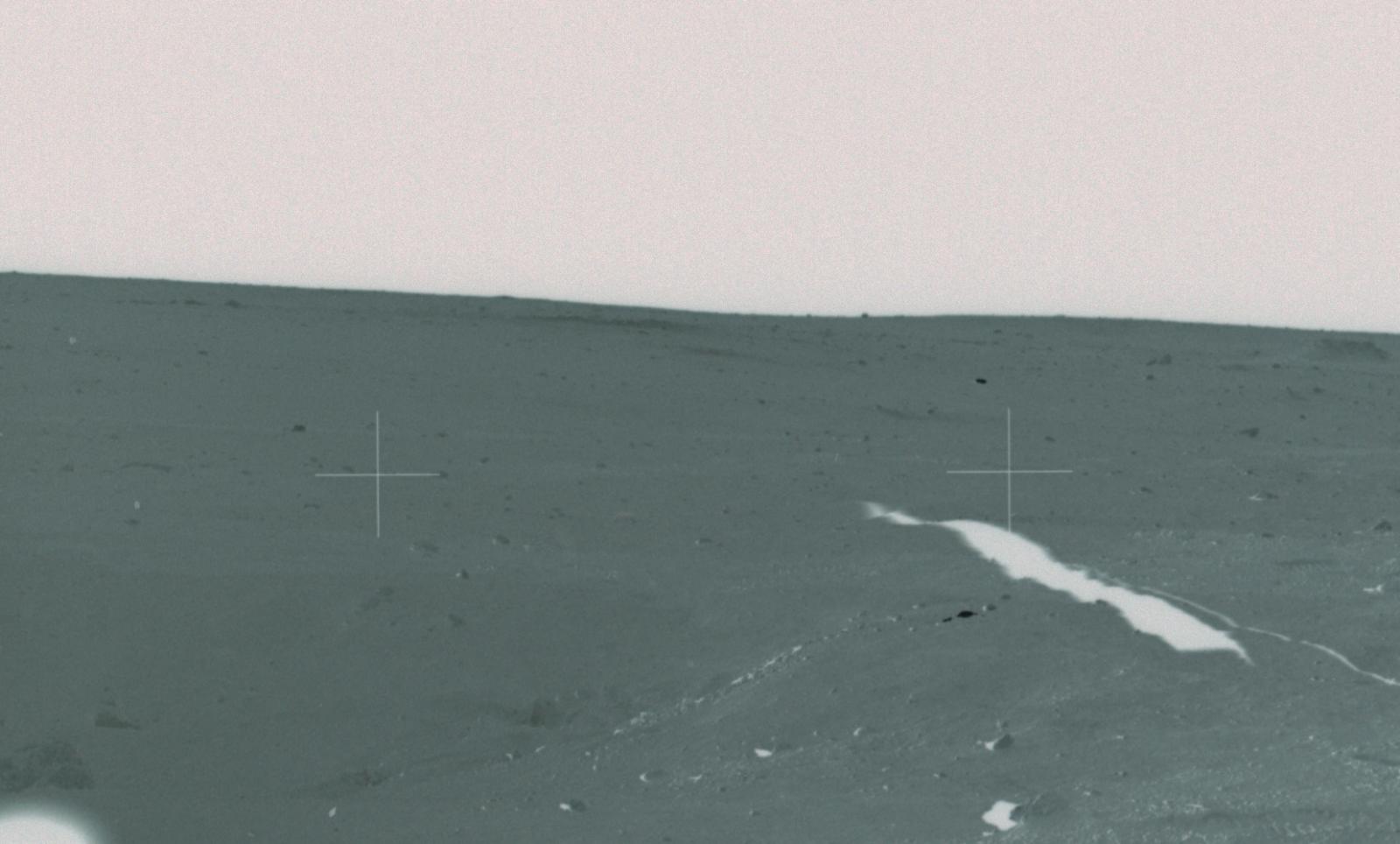

All 34 had been picked up by Border Patrol one or two days before, near one of Arizona’s designated ports of entry. The majority had crossed near Sasabe or Nogales. One man had crossed near Douglas, another near Lukeville.

I was not sure how Ms. Galvez had managed to face the judge alone. It seemed her lawyer had prearranged for her to address the judge directly, with the other immigrants already out of the room. She answered the judge’s questions first. Then, in the middle of answering one, she began to cry:

Please forgive me, she said (in Spanish; the interpreter let her speak, so that, for a moment, her voice was the only sound in the room, then the interpreter translated for the judge). Please forgive me. I am guilty, but I did it for my children. I am a single mother. My children are in Mexico. They need me and I need them. I came to the United States because I wanted to provide for my children. I did not mean to cause any harm. And now I just want to go home.

She was attempting to interpose her story. Her voice contrasted with the silence of the previous 33 women and men, yet resounded with the stories and the individual imperative of each enclosed within that silence. The judge and the lawyers and the primogenital coin were immune; they had heard it before—though they had never heard it before from Ms. Galvez. Which means they had not heard it before, but had purposefully conflated and confused Ms. Galvez’s words with the words of other women and men who had spoken in defense of themselves and on behalf of their families.

The judge could offer only the most lifeless response. He thanked Ms. Galvez for, as he said, sharing her comments, then sentenced her to 30 days in detention.

It was nearing three o’clock.

Ms. Galvez turned to her lawyer. He was neither conscience nor temptation. It could only be assumed he was listening. Then Ms. Galvez was escorted, in handcuffs, waist chain, and leg shackles, out of the courtroom.

I sat in the back row of the gallery. In front of me were twelve women and men; young, riveted, they gave the impression of activists. But they did not look agitated or enraged. They looked funereal. They asked to speak afterwards to the judge. They introduced themselves as students from Prescott College.

Without his black robe, the judge became another citizen white man. Button-down shirt, two sizes too wide, tucked into slacks pulled up too high. He transformed into a stepfather. He strode back to where we were sitting in the gallery. He had the patronizing air of a man from the foothills, the part of Tucson that stretches across the base of the Catalina Mountains that looks out over (down on) the valley. From the foothills, the Tucson valley appears to be a peopleless grid: an ordered chaos of glittering structures in which people are, from a distance, invisible.

The judge had grown up in Tucson and admitted that he had been, until only a few years before, unaware of Operation Streamline. He was, he said, shocked to learn it existed. He was attempting to place himself in the gallery with us, to suggest that he was observing Streamline with the same critical, even incredulous, eye.

By telling us that he grew up in Tucson, he was telling us that he too was human. Once. I could almost believe that he might have originally been compelled to his work by an interest in people and their stories. But bureaucracy is not a brain without a body. Bureaucracy is a body without a brain. It is mouth and stomach and intestines. Whomever the judge was when he entered had not been destroyed but digested and distilled, instead, into the pure example of defensive complicity with which we were now being entertained.

I don’t deport people, he said. This is not an immigration court. This is a criminal court. I’m a judge. I prosecute people for committing crimes. We have nothing to do with deporting people.

I’m a judge sounded like the testimony of an automaton; I’m just doing my job, the willful obtuseness within the banality. That one is recused from complicity, responsibility, by being one person, one institution, removed, from where a life is being taken.

The judge’s denial of having anything to do with deporting people was disingenuous at best, since he kept repeating that deportation is handled by ICE, the agency to which he was directly turning over the women and men he sentenced. His denial, in response to a question no one asked, confirmed that he knew the work he was doing had precisely everything to do with deporting people.

One of the students asked him what he thought of the Streamline process.

It does not matter what I think, the judge said. It is up to you to decide.

Another student asked the judge how he thought the Trump regime would change things at the border.

There’s nothing else that can be done at the border, he said, to which he added, physically speaking. He was referring to the overpopulation of roving patrols, surveillance cameras, fixed towers, implanted motion sensors, and drones that form, in addition to the actual wall, in its many parts, a bloated border industry—and the budget that ensures it. He went on to say that the wall is not, in his opinion, going to manifest in the (further) construction of a physical wall but through an increase in prosecutions. “There could easily be a ramp-up on petty offenses,” he said. The border would become even more bureaucratized and monetized, with immigrant women and men becoming victim to even more comprehensive criminalization; the border would be constructed, piece by piece, out of the welfare of women and men in desperate situations.

And it will be. The vast majority of federal prosecutions are immigration-related, Joanna Williams told me. Williams is Director of Education and Advocacy at Kino Border Initiative in Nogales (on both sides of the border, Arizona and Sonora). I asked her how she thought Operation Streamline might evolve under the current regime. There will be more prosecutions, but less Streamline, she anticipated, adding, from what Attorney General Sessions has said, it seems that people will be charged more frequently with the felony and not offered the plea bargain. Streamline as a program only works if people are taking pleas to misdemeanors, since the felony process requires more steps. Then again, if the prosecutor doesn’t use Streamline, it will require significantly more judicial resources to prosecute even the existing number of cases.

Operation Streamline is only one border-sector-specific facet of the seemingly inexhaustible expansion of unauthorized entry and re-entry prosecution happening all over the country. The criminalization of unauthorized immigration will not operate under a single, locatable name but will be (and already is) more viral, more shape-shifting.

The United States border extends (and is extending) even deeper into the country, overseas, to other continents, but maybe most importantly into the human—the mind first, then the body, against which the border was originally dreamed. The border’s dream is for undocumented immigrants to be its most reliable missionaries. But the immigrant who crosses the border is the affirmation of a life that transcends borders. How many of the 34 women and men, how many of the immigrants who are streamlined will cross the border again?

People are going to keep coming, says Hortencia Medina, an organizer in Texas whose brother was convicted of unauthorized entry and re-entry. There are some people who say, ‘We’re going to put big bars beside the river so people won’t cross.’ We, as human beings, are going to say, ‘How can we cross?’ That won’t be an impediment to us—you make a tunnel below or a ladder above and you cross.

Medina is one of many individuals—immigrants, family members—whose experiences are included in a monumental assessment of the costs and failures of Operation Streamline and its synonymous programs, cowritten by Grassroots Leadership (Austin, Texas) and Justice Strategies (Brooklyn). According to Grassroots Leadership, most data and qualitative research—as well as immigrant testimony—demonstrates that migration is largely dictated by economic climate, not enforcement mechanisms. And according to the Center for Latin American Studies at the University of Arizona (Tucson), a far stronger influence than either criminal court or deportation on immigrants’ motivation to cross and re-cross the border are family ties.

Meanwhile, court and incarceration costs, paid for with taxpayer money, are extortionate. Taxpayers also fund the privately owned prisons in which the immigrants are detained. The prisons’ annual revenue has, in the years since Streamline’s inception, skyrocketed.

To streamline is to eliminate resistance. One way of eliminating resistance is to incorporate the resistant body. Streamline thrives on the formation of undocumented immigrants into contributory elements—to fill courtrooms, cells, beds. Undocumented immigrants are needed to form a permanent demographic, which suggests another definition: to eliminate resistance in immigrants by waving the American flag before their faces, while at the same time indicting them, behind the flag, as symbols of what the flag is waving against.

How many children does Ms. Galvez have? What are their names? How old are they? Who is taking care of them? Where do they think their mother is? When is the last time they saw her? Without Ms. Galvez’s interjection, her children might have not even existed in the court’s imagination. That she mentioned her children threatened to short-circuit the court.

The demonization of individuals makes their having a family (therefore communities, histories, and futures) inconceivable, unless you conceive of their family as demons. Enforcement mentality fantasizes family on the other side of a border as a kind of uncontrollable obstinacy. The court was also passing judgment, through the body of Ms. Galvez, on her children (communities, histories, futures). Because it could be argued that the actual targets of such immigration laws and enforcement are those for whom immigrants risk their lives—one generation, two generations, three generations ahead.

It is easy, in a space designed to bleed people of their stories, for the imagination to go dark and stay dark. It was the first week of February. Ms. Galvez would emerge, the first week of March, from 30 days in detention and into the cold calculations of ICE, women and men who may or may not have cultivated for themselves a personal philosophy of what it means to be an American, but who are, in their devotion to the bureaucracy of injustice, acting it out. It should not have to be a question of what it means to be an American, because the answer to that question is already synonymous with the annihilation of those who are already endangered. It should be a question of what it means to be human, which is increasingly beyond the capacity, and the consciousness, wherever it can be gleaned, of the law.