Splurging, against the grain of my better judgment, I purchase front-row tickets to see the 2018 Broadway revival of Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes. I have to sit this close, throw down this much money, even go alone, because Angels in America is the first gay anything I saw as a kid. Set in the late ’80s New York City, the play primarily follows the life of Prior Walter (played by Andrew Garfield in the revival) as he lives with AIDS, is visited by angels and ancestors, and tries to make it into the new millennium. I watch this play-turned-HBO-miniseries on my living-room TV, my family asleep, the volume so low you can barely hear it. I buy the script, read it from front cover to back, highlight its pages in green trying to memorize the lines and the grandeur I have endowed them with. The development of my queer consciousness, my man-kissing-man sensibility, begins here with Angels in America.

It’s an argument with a dead end, at the dead end before we even turn onto the road:

“Why do you let this get to you? What is AIDS to you?”

What a question, what a conundrum of further questions. I thought he loved me? What is AIDS to me? The condition of its being AIDS?

AIDs is ____________________.

a) Africa, a continent of black children on those commercials, crying and emaciated, images on my TV screen more distant than near, their bodies depoliticized and dehistoricized.

b) a footnote in my 11th-grade history textbook (or was it an actual section in the chapter focusing on the Reagan years and the fall of the Berlin Wall, a section we did not have to read, because the teacher did not find it important or relevant enough to read?).

c) a bald Tom Hanks in the film Philadelphia.

d) the jokes the little white boys and white girls of my school would say to one another on occasion, in passing:

i) “You look like you have AIDS, Timmy!”

ii) “Don’t touch me, Mary, you might have AIDS!”

iii) “Becky, what even is AIDS?”

e) Magic Johnson.

f) ACT UP.

g) a tío who died from, according to his obituary, “his illness.” I, in the womb of my mother, a fetus of her trials and tribulations, am born a month after my tío dies from “his illness,” which no one dares to call AIDS.

h) gay men.

i) all of the above.

There I am, front and center. The tinkling of golden bangles, the expensive perfume hanging from those with the hushed voices discussing the shows of the season. This is the first time I have ever been this close to a Broadway stage, so close I can touch. I can see the stagehands in the wings. Actor Nathan Lane’s wrinkles wink at me. Playing Prior, Andrew Garfield’s saliva nearly strikes me. I tell my mother about the seat I purchased and she thinks I’m moving on up, a man of the town, a somebody. I feel good here in the front row. I feel powerful here in the front row. I feel I am the critic here in the fr—

It’s just makeup. Powder, concealer, contouring. Lumpy looking, layered and thick, an aberration. Someone gets paid to do this, to make a fiction of AIDS into the real and to make a reality of AIDS into fiction. Prior disrobes. The thin white skin is revealed, his bareness marked with purplish dark. Official medical name: Kaposi’s sarcoma. KS. The overloaded symbol of AIDS. Google offers horrifying images of KS. Bloated purple masses, spotted purple backs, purple sores in close-up. I can’t look away.

A palpable silence in the audience at this exposure. A palpable stiffening of the body from those of us in the front row, bodies in attention, struck and startled. Have they seen the circulated images of these lesions? I’m sure these lesions are a memory some can remember, and, who knows, some might have lived. Some who have never seen it in person, like me, are transfixed, transformed. I cross my legs, all prim and proper, and bear witness to the fiction.

“Qué es el SIDA para ti?” A cringe, a swallow, a netherworld pain is my grandmother’s response. Her cringing says, how dare you, boy, foolish boy who knows nothing, boy who dares to think he knows everything, boy who knows no history. I feel childish for asking an old woman of AIDS. AIDS, those four letters, those letters that took away her son, my tío. Who am I to ask her to remember? Remembering in language an illness that was never language to her. An illness materialized on the body that was unspeakable, unbearable, to her Caribbean sensibilities that have been dictated for so long by coloniality, those New World logics that erase, obliterate, anything against the beat and time of European heteronormativity. I ask her the question and her eyes remain on the TV. Her brown eyes are a story told in images, flashing memories flashing fictions: a man, a woman, a hand on the body touching, her hands on lesions purple and plump, relatives, afraid of contagion, refusing to sip a café con leche, refusing to hold the handle of a mug, him in a bathtub, a grown man scrubbed and sponged and washed by his mother, disease and queerness, the queerness of a disease, a house of the Puerto Rican diaspora plagued by a plague, tropic hands tendering first-world illness.

Prior is now in a hospital bed, purple lesions visible, out in the open on the stage. Hannah, Joe’s mother, Prior’s ex-boyfriend’s lover’s mother, a Mormon through and through, is on the opposite side of the stage. Prior has been fighting AIDS the whole play, and he has now reached the point where the disease consumes him, now dependent on people like Hannah to care for him. Care is a structuring thematic in the play. The play begins with Prior telling his boyfriend, Louis, of his seropositivity, and the downward spiral of their relationship through the play because Louis is unable to give that care, a care that is unbearable because Prior’s body is burdened by meaning, by AIDS and its meanings. Care, and the associating of care to disease and queerness, becomes the means through which the characters relate and the narrative unfolds. There is Joe, a pro-Reagan Republican, who, while falling for Louis, in need of queer care, is unable to tend to the needs of his wife, Harper. Belize, friend of Prior and a nurse, cares for Prior and Roy Cohn, physically and emotionally. Prior and Harper have visions, hallucinations, otherworldly experiences that become a means of being cared for when living in isolation, when feeling alone. The economics of care—who will get it, its scarcities and abundances, how it will be distributed—governs the motions of the play.

Here in the front row I can see Hannah is uncomfortable with caring for Prior: fingers fidgeting, feet shifting uneasily, the face pinched and tight. The playwright, Tony Kushner, writes empathy into the moment: Prior spasms, she inches a little closer; Prior coughs violently, a little further in his direction. The violence of the body wins her over.

There is precedent to her response. AIDS is aura and the queer body is an aura of AIDS: the woman on the subway uncomfortable when I kiss my loverboy, as if our kiss were contagion; the boys on the street disturbed at how short my shorts are, as if, if they got too close, if they stared too hard, I could infect them; the straight-identified men who have sex with me and enjoy me and revere me through a distance they want to bridge but do not know how to cross. My boyfriend and I say to ourselves, if we were living in the ’80s and ’90s as gay men we would probably be dead. Would we? Would anyone have cared for us? Would we have cared for each other? Would anyone have even known we died?

“What is AIDS to you?” Theory. Intellectuals intellectualizing a virus, mass death, an epidemic, queer lives. AIDS as subject of thought. Susan Sontag with the grey streak through her hair writing AIDS and Its Metaphors. Leo Bersani’s essay “Is the Rectum a Grave,” which I had to read in a queer theory course in undergrad and then graduate school. Jacques Derrida doing whatever Derrida wants to do with a word, a body, a queer, a disease, a discourse.

Words feel insufficient, so when Angels in America on HBO materializes AIDS, I understand it differently. It is no longer the abstract and vague history lesson that happens in the classroom, the slur from the other students, or high theory. The visual elaborates, the visual speaks what cannot, or refuses to, be spoken. It is the “straight” Roy Cohn (played by Al Pacino) bespeckled in lesions. It is Prior on the floor with shitted and bloodied pants. It is the Mormon mother staring at the diseased body.

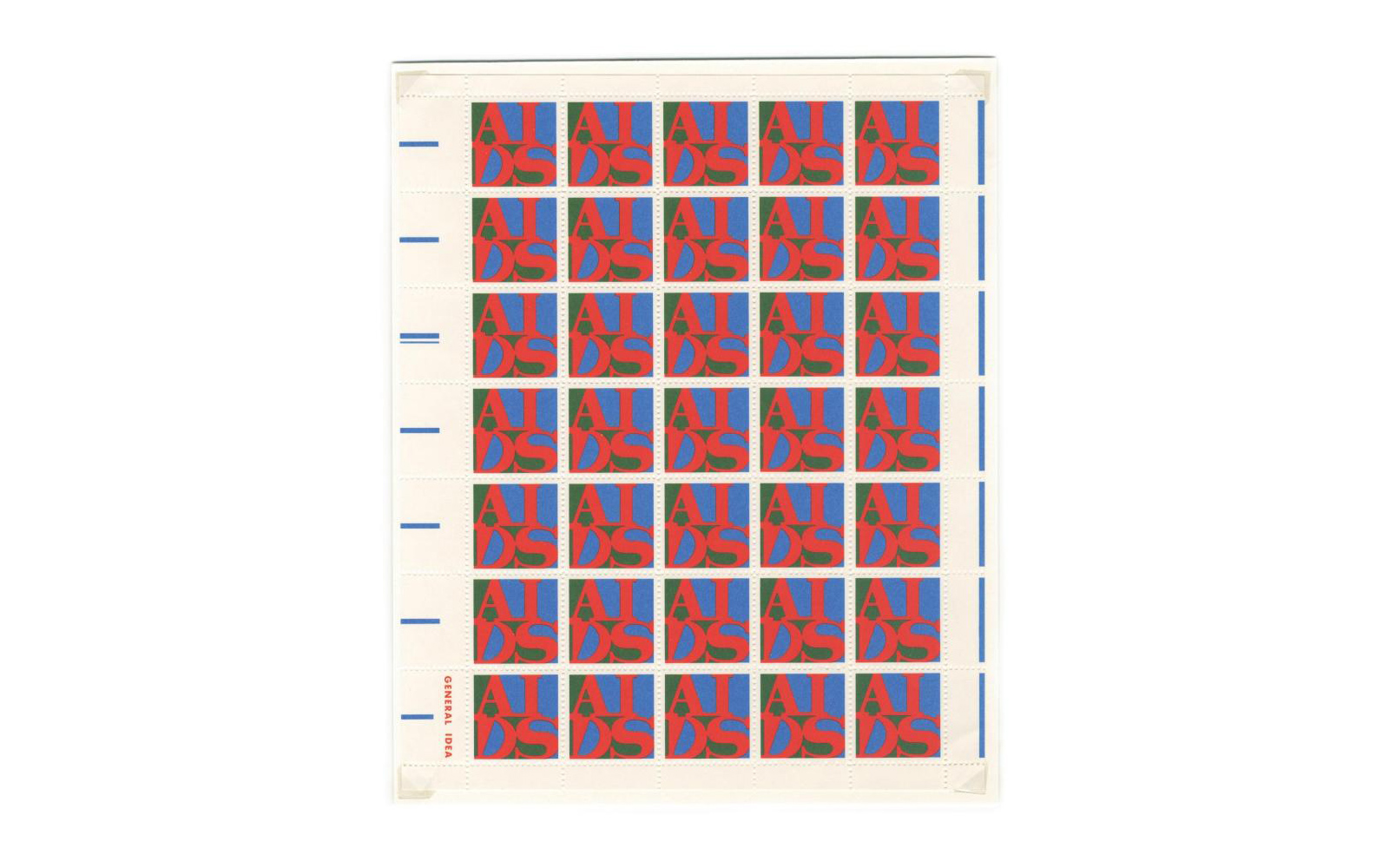

I want AIDS represented in words with my family. As an idea, a history, a discourse in language. But then there I go finding myself unsatisfied when prominent theorists turn AIDS into language, turning it into ideas, historical record and discourse. Maybe what AIDS is is a contradiction. Wanting one thing, saying another. If AIDS has a logic, maybe that logic is that nothing is ever enough. That nothing will do, that nothing will ever be able to represent those four capitalized letters, that an A and an I and a D and an S brought together can never represent what my tío might have gone through when the doctor told him he would live with, and die of: AIDS.

Intermission. The line to the men’s bathroom wraps around the theater. A lot of gay men, a lot of white gay men. They probably lost friends, hookups, lovers, boyfriends to AIDS. It is a plural S, always more than one at a time. To imagine such scale of death is something I cannot comprehend. The singular—my brother dying, my tío dying, my grandmother dying—I can comprehend this. I have lived this. But to sit and watch and have to tally up, account for death, be a statistic of death, is unimaginable. To read obituary after obituary of those you have known, those whom you have shared a coffee with, a laugh, a dance, a blowjob—unbearable. And yet this is nothing new for those who have had to continue living after a drone strike decimated their village, after a nuclear bomb vaporized their city, after bullets gunned down their kin and kind in mass. Mourning in mass. How to account for the specificity of a life when one must mourn many lives at once? These death spectacles are large in scale and wide in scope. AIDS has become such a spectacle, a memory of mass death, much like the Holocaust, the Plague, the Rwandan genocide. What of those who die slowly, slowly dying from illness, fatigue, violence, dying unspectacular deaths in large numbers across time? Trans women of color are murdered in the singular, a day on the internet dedicated to trying to apprehend and condemn the brutality and grotesqueness of their death, a body spectacularized for a moment. Then each year tallies are given of how many trans women of color are murdered. The statistic is meant to shock, the tallied up body count a call to action, and yet here we are, a new year, a new tally beginning.

“What is AIDS to you?” Poetry. Let that morbidity sink in. Hemphill, Saint, Dixon. Black queer poets, specifically. I purchase Essex Hemphill’s Ceremonies on eBay after years of reading about him in scholarly articles and monographs. Always citations, references, shout-outs, but never did we read his actual work. The poetic protest, the poetic fury in “When My Brother Fell”: “I realize sewing quilts / will not bring you back / nor save us.” AIDS is not to be responded to by sentimental gestures, the sewing and stitching of a quilt on the lawn of the white house. “A needle and thread / were not among / his things / I found.” All that fabric stored in Washington for what? Whom does such memorializing serve? “It’s too soon / to make monuments / for all we are losing,” but is it ever the right time for memorializing? To say, here is where it ends, here and now is when we move on?

Abbreviated portraits of men who were and no longer are. Men nevermore in Assotto Saint’s poem “De Profundis: for eleven gay men in my building.” The ordinary that is “strolls through Chelsea,” the craving of “french fries kiwis gin” after a night out dancing, those ordinary indexes of love, and then “i tried to see anything but his casket / gorged by the ground / the tears were for myself / one day / i shall be in this / darkness.” Love loss, the loss of love, the never sucking never fucking never bottoming for never topping never kissing a beloved again. The abyss, like love, that is loss. “This poem is for,” begins each of Melvin Dixon’s stanzas in his poem “And These Are Just a Few,” each stanza in honor of a life, giving life to names. Will . . . Joe . . . Sam . . . Grid . . . “I’m sorry to report that of the twenty people mentioned in the poem, only two are presently alive,” he reports in a speech he gave near the time of his death. Juan . . . Tyrone . . . Elijah . . . Carlos . . . to speak their names to speak their absence to speak their presence to speak their bodies to speak their love—the function of obituary.

Poems like obituaries, obituaries that must be poems. Is that the poetics of AIDS? More than mourning, more than elegy, more than death. In my grandmother’s house, in a plastic container enveloped with decades-old dust, there is a newspaper clipping. It is my tío’s obituary, or a part of it. Someone has clipped out the details of his life (where he was born, the accomplishments of his life, other insignificant details) leaving only the words “his illness” and some of the section of who he is survived by. All this done as if to let whoever may see this next know this once was an obituary, as if letting this future person know that “his illness,” that vague and erasing phrasing so common during the ’80s and ’90s, was not just an illness but ____________________.

erasure.

a queer Puerto Rican life.

a discourse.

There’s a nice-looking couple sitting next to me. White and heterosexual and cisgender. At least they appear so. What does AIDS mean to them? Did an uncle die of it? Did they hear about it in a film, a footnote in a textbook, a text from a course they took? Does AIDS need to mean any one thing? Does AIDS need to mean anything to them at all?

“What is AIDS to you?”

The purple lesions but, according to my mother, my tío had none. My family didn’t even (want to) believe he had AIDS. Is it AIDS, then, that he dies of? Angels in America has me believe AIDS must mean those purple lesions. That it is the sign of AIDS, so when composing my uncle’s biography in my head, in my notebook, in the unfinished drafts on my Dropbox, I put those lesions on his body. One, two, three, a few more of them. Big and visible and a dark purple. My imagination runs wild until my mother’s testimony forces a revision. Without those purple marks, the narrative feels wrong, like it no longer makes sense, as if AIDS only makes sense with those lesions, as if AIDS can be made to make sense.

The seizures. My mother tells me he started having them so bad that he had to return home, that he had to confess to my family he had indeed contracted the gay virus, that he was in fact contagious, that he was in fact a man who had sex with men. Prior had seizures in the play, so my uncle’s story feels more authentic, legible, as AIDS. Seizures, unlike the purple lesions, are not archivable. We cannot photograph a seizure, or record it, the act of documenting taboo given that the happening of a seizure is violent, unexpected, dangerous. My mother cannot bring into words what it was like to witness these seizures. The fear in the moment, and the fear of remembering them, has removed these memories of seizures, these memories of AIDS, from the archive. Who wiped away the foam from his mouth?

The shitted pants. My tío too weak, too frail, too low on T cells to make it to the bathroom. Much like Prior in the play. More authenticity to the narrative. Who sponged away the shit from his ass? Who made him feel clean?

Unprotected sex. No need to find validation in Angels in America. Unprotected sex still signifies AIDS, disease, queers, death. This is how I write my tío’s story. One night, many nights, many years, unprotected. Cruising, in a park, anon, in a stranger’s bed, unprotected. One lover, three lovers, a boyfriend, unprotected. The fear of seropositivity, the fear queers are told to have over seropositivity, the fear of what our bodies can do when unrestrained, when desiring, when wild, when loving, when unprotected. His biography becomes mine, for an instance, for a moment, ours, this queer, transcendent time. Yet still this extension of myself, of my own relation to unprotected sex, can only go so far. Who was my tío’s boyfriend? Did he have a boyfriend? Did he cruise the theaters of 42nd Street, the bathrooms of Central Park, a sauna in Chelsea? How did he contract the virus? There is no one left alive who knows.

I want to say what I know of my tío is more than suffering. I know he liked Skor chocolate bars, because my mother told me so. I know he was a messy person, because my grandmother’s dementia told me so. I know he told jokes on the back of photographs, because I have found a few in my grandmother’s house. I want to say AIDS is more than suffering. That it is resistance and pleasure and the ordinary and joy and life. How can I say such things? AIDS as pleasure? AIDS as joy? AIDS as ordinary? Who am I to say such things? This queer of color who only knows stories about AIDS, who reads literature about AIDS, watches plays about AIDS, reading and studying it voraciously in efforts to know, achingly and desperately trying to know, be closer to, to fathom what it must have been like, what my tío must have gone through, what it was like to have been a Puerto Rican queer in the world, all that fucking, all that rice and beans, all that laughter, all that kink, all that salsa dancing, all that love, gone.

The final scene. Prior’s alive, he’s surviving. He’s with his friends, joking, bickering, discussing the fall of the Berlin Wall, the West Bank, the new millennium. The statue of Bethesda, the angel, looms above them, watchful and majestic, her presence a purifying of the stage, a cleansing of the soiled bedsheets, the purple lesions, the shitted pants, the infected. Such hope on the stage, all the warm fuzzy feelings, another day to celebrate, another day to live. I see the couple next to me smiling. Everyone in the front row is smiling. All’s well that ends well.

I sigh. This is New York City in 2018: post–Marriage Equality, post–Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, post–Gay Liberation. The feeling of post-ness makes this front row smile, makes this audience sigh in relief, letting their bodies relax. The lesions on the body, the hesitant footsteps towards the diseased body, the contaminated blood on the floor—that’s all over. Queers have progressed out of this narrative. Queers are progress itself. In 1992, the year Angels in America is premiered, this final scene might have been necessary. Queers living with AIDS were probably in the audience. Someone who needed to see queer survival needed this. What about now?

This now that I write in, queers raising children in middle-class suburbia, queers nearly naked gyrating next to police on parades floating down Fifth Avenue, queers begging to be just like everyone else, what do queers need? This now that I write in, queer teenagers homeless on the streets, queers of color murdered on the streets they call home, in their homes, in their schools and in their nightclubs, what do queers need? This now that I write in, queers living with PrEP, queers living with seropositivity, queers living with the legacies of AIDS, what do queers need?

Once upon a time, Angels in America was what I needed as a queer. This play told me something about what it meant to be gay in New York City, what it meant to live with a disease, and die of disease, in the ’80s and ’90s, what it meant to confront AIDS. Now, in this year of 2018, as a queer of color, as an unashamedly loud queer of color, as a queer of color who reads as much as he can about AIDS, the profundity of AIDS seems like something Angels in America cannot capture. Perhaps, AIDS, as a phenomenon, as a plague, as poetry, as letters, as theory, as a discourse, is something unrepresentable. Uncontainable within the boundaries of even a protracted six-hour play. Perhaps any attempt to speak on behalf of AIDS is already doomed to fail. Perhaps that’s what AIDS is.

I sigh. Sighing heavy like my tío might have done at the final hour. Sighing a Caribbean breath into the atmosphere. Sighing exasperation like the queen I know he was. Sighing that sigh no stage on Broadway would dare to try and represent.

“What is AIDS to you?”

AIDS is _______________________.

a) a revival of a play on Broadway.

b) endnotes and footnotes in some textbook.

c) a gay man’s disease, a white Western gay man’s disease, just a disease.

d) over and done with.

f) none of the above.