In December 2021, Cooper Cole exhibited Timothy Yanick Hunter’s solo exhibition, Volcanic Spine. The exhibit, set in a stark white room, has four pieces: “Untitled (Loop 1),” “Untitled (Loop 2),” “No More Accidents,” and “Pelée's Tower.” Each composition is an expression of different archival moments from black history: traffic accident rates, repeated photographs of a volcanic eruption, home movies, the book Born to Slow Horses by poet Kamau Brathwaite, cricket, the Caribbean market, Jamaica’s People’s National Party.

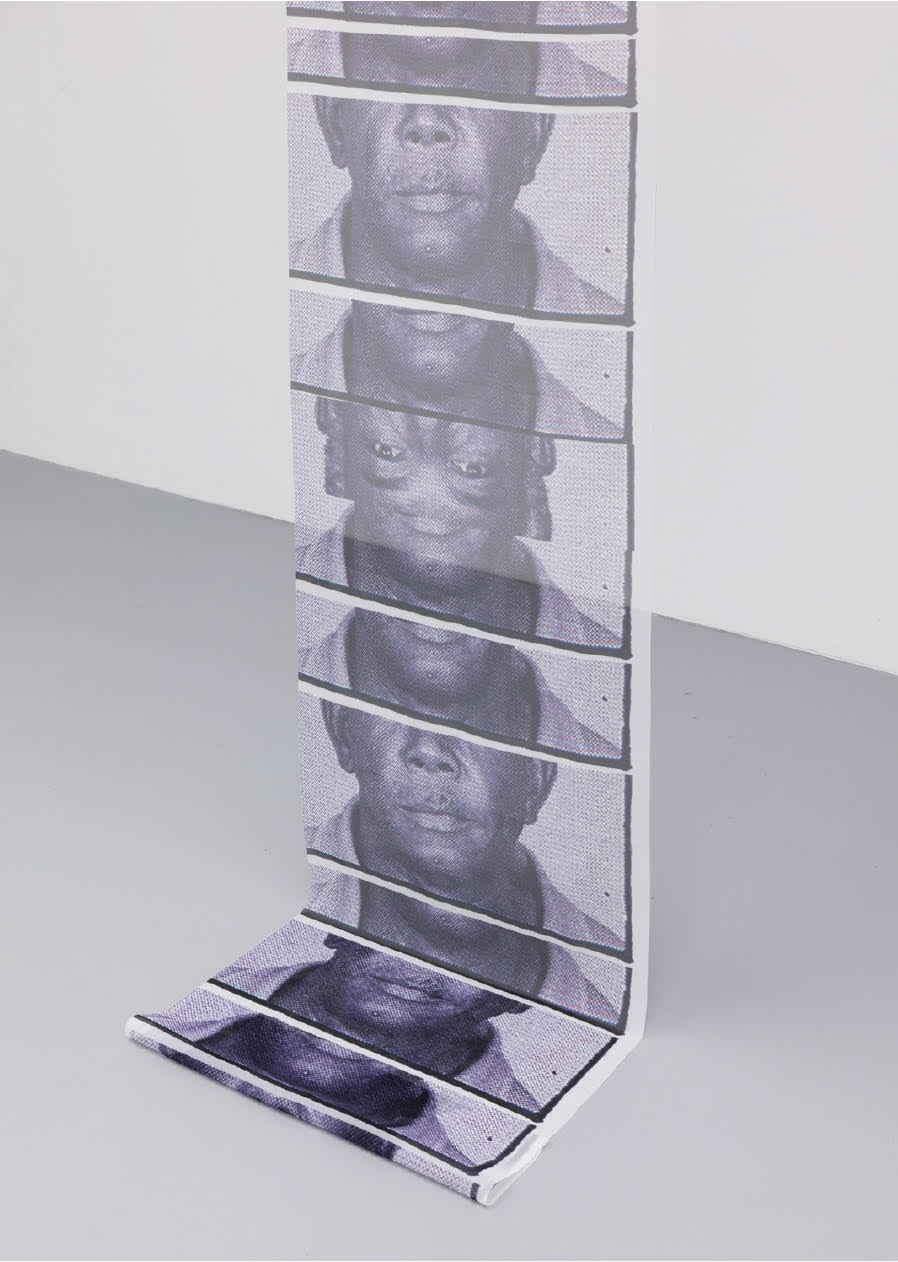

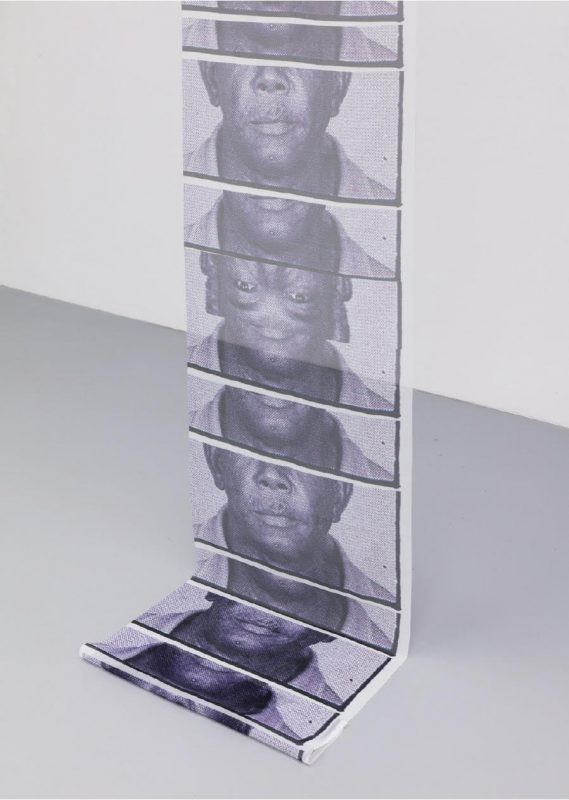

The materials, visual cues and invocations vary. Volcanic images are presented on voile fabric print and are placed overhead, draped across the ceiling. Repeated photographs of Jamaican Deputy Prime Minister Seymour Mullings, also on voile fabric print, stretch from the ceiling and onto the floor. Televisions are encased in metal, cement board, wood. The videos—single-channel, two-channel—are looped and accompanied by mashed-up soundtracks composed of voices, ambient undertones, jazz samples, light soul beats.

Volcanic Spine offers fragmented histories, sounds and textures, all of which collapse into expressions of diasporic curiosity: visual and textual prompts that momentarily signal, but do not totally reveal, shards of global black histories. In placing different worlds together—fabric and screens and song and earth ruptures and Brathwaite and Ghanaian brigadier William Akuffo—Hunter visually offers a series of uneasy contradictions. How do we think screens and fabric together? How do we connect the ocean to gridlock? How are these soundtracks fusing different times and spaces? What happened after the volcanic rupture, after the traffic accident? The contradictions and questions are not resolved. Instead, unknowingness and vulnerability hover.

Hunter manipulates time and space by slowing down and speeding up and layering multi-textures; what is not supposed to be there (here)—black aesthetics—emerges momentarily, gets tethered to elsewhere, and is made into a different kind of facsimile. Using visual and sonic loops and looping techniques throughout the installation, he gestures to and builds on the work of black artists who manipulate, splice, and reinvent existing sound samples and tracks to reconfigure music.

The practice of looping also relies on repetition and return; the art of looping is a studied, measured and persistent intervention into colonial time-space, filled up with collaged and collated texts and sounds. The intervention is a creative act that speaks to the praxis that underlies Volcanic Spine. Hunter describes his art as inextricably tied to research; inquiry punctuates the creative practice and text. Or, research (reading, studying, writing, questioning, searching, experimenting) is art. With this, the constraints of race thinking are unsettled, callous racial-sexual categories and positivist grammars are named and abandoned, and a black creative worlds contradict, spiral and unfurl.

In February 2022 I interviewed Timothy Yanick Hunter about Volcanic Spine. We talked about origins and found objects and screens and J Dilla and studying-as-art-practice and note taking and chopping and loops. I learned about pace and invention and repetitive interruptions and curiosity as vulnerability.

Katherine: Volcanic Spine provides us with different and overlapping entry points into some visual texts that are animated by the black diaspora. Who inspired this project?

Tim: One of the most notable influences would be Wangechi Mutu and her collage work. I was studying art history in my undergraduate degree, and I had an assignment where you had to submit an exhibition review. Before that time, I never really had exposure to art in an institution, like at the Art Gallery of Ontario. So Mutu’s exhibit was my first exposure to contemporary work within a gallery setting. She produces these beautiful collages mixed with ink drawings and ink paintings. I never saw artwork by a Black artist at that scale—and I was so enamored by it, and from that day, thought, "Oh, I want to make a body of work like Mutu's collage series." So, that's my origin story.

Katherine: That was one of Mutu’s very first solo exhibitions in North America, at the AGO, in 2010. She’d never had a show to that scale yet, from what I remember—it was called This You Call Civilization? I remember it well! I remember there were the bloody bullet holes on the walls and these unsettling massive collages. There were also glass cases of found pictures and smaller collages. It was both an installation and a set of collage on the wall.

Tim: Exactly. And I think that's one of the things that drew me to the work, because at the time, I had kind of a narrow view of art. I was studying and learning on my own and using the internet to look at artwork and thinking it through not in an institutional sense, but through my own research. Mutu showed what it means when black objects enter the gallery space, and what it means to create an environment with your artwork. And again, who knows. I'm thinking back to it, that might have been my first time even walking into the AGO.

Katherine: That is a whole experience in itself, right? Walking into a curated space, walking into a building that is so often curated for white viewership and audiences, and then going in and seeing these mangled Mutu bodies.

Tim: Totally, yeah.

Katherine: And I think one of the things about your work that I like is that you enter into the space and you insist that art isn't flat or two-dimensional, but that it's a bigger experience. A lot of installations work in this way, but you're also working with several creative invocations, like televisual images, sounds, and fabrics, which thicken the space.The idea of collaging and putting things together is part of that thickening. Can you talk a bit about your method and the act of entwining images and sounds and textures? What guides how you make things, I guess, is the question?

Tim: When it comes down to putting different things together by layering and looping, then whether it's a video or sound or image, I think of Black music as my main inspiration. Before Mutu, my main adolescent influence was rap, which led me to think about producing and the art of sampling. So, whether I'm working with an image or a video, I go into it with that feeling where it's like I'm digging for samples. The first student loan check I received, I went and bought turntables and I started going to record shops.

Katherine: Yes! Yes, you did.

Tim: Yeah, I spent a lot of money, a lot of my student loan funds, doing that for a few years. And I was just so excited to go through sonic material like that. I think seeing Mutu's work helped me think about that—the digging and the sounds and putting different music together in terms of flat 2D images with paper. But also, I think my process is definitely tied to the idea of selecting and arranging different texts, kind of like DJing or sampling. So, I might find a video of an interview with a writer or something and pair that with some obscure R&B track. I think the process is intuitive. But there is also this underlying attempt of paying homage to contemporary forms of Black cultural production and to explore archives and share my findings.

Katherine: I wanted to talk to you about that idea of sharing (sampling, DJing, collaging) in relation to citation. Because one of the important things that Black Studies and Black creative works offer is sampling and citations as a way to make the world legible. But at times, the citation or the sample is very specific to Black people. So, the obscure soul sample is obscured for some, but it might invoke nostalgia or a joyful memory or a clear feeling of loss for someone else. I'm thinking of J. Dilla or someone like that, and how he employed longer samples, shards of songs that were identifiable. He is asking us to pay homage to a particular genre of song history. But not everybody has access to that history. And so, there's something interesting about your method as a version of that kind of sampling. You are putting things together intuitively, but you are also cautious and patient. You don't just throw anything together. You think about how to share what you find.

Tim: With someone like Dilla, there’s an intentionality in the sample beyond audio or visual aesthetics. I think of it like a research process. You're studying a genre, sometimes over the course of months or years. I'll be like, "Oh, South African jazz." And that can spark the beginning of the research process. Then I start to develop batches of samples and sounds. Music-making is also part of the research process. I'll be chopping samples and playing with them and arranging them and creating something new. So thinking back to Dilla or anyone who's ever worked really in that framework and that practice—there's something just magical about being able to take fifteen seconds of a longer piece and then creating something brand new out of it, but still be paying homage to that bigger research batch I'm drawing from.

Katherine: Mark Campbell talks about this. His new book, Afrosonic Life also uses that kind of language—the beauty of making and inventing. What does it mean when we take a piece of something and invent or reinvent the world around us? Or what happens when we take a moment and ask it to do something different than it was originally intended to do? This comes up in your work a lot. You don't just use photography, you don't just use collage, but you use televisions, and you use soundtracks and found objects. So maybe you can talk a little bit about the different kinds of materials you use in Volcanic Spine. You bring these big TVs into the room and the way they are placed, it means we must look into the screen in a particular kind of way—we might have to crouch or look down. What are you trying to piece together with the kinds of material you work with?

Tim: I've always been multidisciplinary. I think my work now is a more synthesized version of what I was trying to do before anyone was really seeing my art, when I was just working in my grandma's basement. I was painting things and making collages and at the same time and then I would make music. And I kept them in very separate places. It was just, "Oh I should show paintings, but I'll keep the music to myself. And then the collages, I'm still developing." But I think from a raw art making standpoint, for me, I'm never really just satisfied with any singular object or singular way of exhibiting work.

Beyond that, I think of how technology informs our lives and art making practices. Just like the idea of sampling, digging through archives, DJing, the idea of somebody taking the turntable and creating something brand new out of these pieces of technology. This translates in the exhibition space, where I engage with the television as a screen that is in some ways a marker of the time we're in, whether it's the TV screen or the computer or our phone. And so, for example, “Pélees Tower” has a screen facing upwards, so that the audience has to lean over and engage with this large video from above. I was thinking about how the orientation of the television screen makes us think differently or engage differently with an artwork. I am not the first person to show a screen like that, but the idea is to consider how the position of the screen reorients us.

Katherine: I was drawn to your use of fabric in “Untitled (Loop 2)”–it looks like an explosion on fabric. I appreciate the contradictions you are giving us. In a sense, it is a photograph of the volcano. And yet you have placed it on something that we can touch—this cotton kind of gauze fabric—that's like a sensory tool, something touchable or soft. But it's also something that we can't have. It's an image that we're distanced from. So, it draws you in because it's touchable, but at the same time, it pulls you back, because your experience with the volcano is necessarily elsewhere... You’re in the same room, but you're not in the same room.And it is placed on the ceiling, so it is touchable but not accessible.

Tim: And this translucency too. You can see through these images. I guess thinking about the weight of the image, the volcano, but also contradicting that weight with this soft material.

Katherine: Yeah. Where it's almost fragile. And, like you said, it's translucent. It's heavy, but it's not. There are so many different oppositions at play. That's what the aesthetic synthesis is doing. It's bringing together things, putting things together that shouldn't be together, but at the same time, it's holding the contradiction steady.

Tim: I guess that's something I've always been trying to work with—connecting things that are seemingly in opposition. And again, I think back to music making and sampling and DJing and how that is done so effectively. I worked at nightclubs for years. I got to listen to the DJs and talk with them and see how they work. I thought it was so interesting, again, that process of being able to take maybe two seemingly almost unlike records, but then you could find this thread between them. And it's intentional. You're building the mix before you hit the stage, but also you’re improvising. I always thought that was something I wanted to accomplish in my work: how do you take these two different feelings or objects and put them together? Like concrete and a TV screen–how do you make those two things feel like a solid whole object?

Katherine: This is what W.E.B. Dubois talks about a little in The Souls of Black Folk: the two striving souls, and what it means to be black and part of a nation that continually excises and displaces you. So how do we live as a contradiction, and how do we embody that contradiction and navigate the world? Black visual artists attend to that contradiction differently. So Mutu does it one way, Kara Walker does it another way; Krista Franklin or Lorna Simpson or Sadie Barnette take this up, too, but in really different ways. In your work, you're in some ways extending that conversation about what we do with these paradoxes and contradictions, and acknowledging what you place in the installation, what is sitting in front of us, is not only an expression of black life, but also in part how we live and invent blackness. What does it mean that black musicians are idolized and mimicked and yet, at the same time, black people are the most despised community on the planet? It comes up over and over again! More repetition!

Tim: That's exactly what I've been thinking through—how to bring a language to those contradictions. I think this is the reason why I always go back to the archive.. I don't feel like I'm necessarily bringing any brand new ideas necessarily, but I do think it's a re-investigation of what is laid in front of me, and my goal is to go deeper into it.

Katherine: You called your creative practice a research process, which is really very cool. It’s very Wynteresque, because you're telling us that creative and academic processes are necessarily interconnected. You are not placing the creative work or even creative workspaces in one room, on its own, and then leaving that room and reading history books elsewhere. You are saying that your process is chopping samples, studying, working with screens and fabrics, moving concrete, reading, digging, researching, returning, rewriting. In Volcanic Spine, the creative-intellectual world behind the installation is one of enmeshment. Your research is creativity and creativity is research. Can you talk a bit more about this process? Where do you access your archives?

Tim: My initial thoughts around the art and art practice being research really comes from being a young black kid in a Canadian school system. We didn’t learn much about black history. I think about my creative practice as research because I feel like I'm really using my work as a way to study.

And again, it's just thinking about this hierarchy of academia and art and creativity. White supremacy emphasizes this top down approach, where some knowledge bases are privileged over others. I love Dear Science because it thinks about art as theory and theory as creative text, and shows how that dynamism works.

As for the actual creative process, it goes so many different directions. It might start with reading. For example, I was doing some research about the Medu Art Ensemble and the anti- apartheid resistance in South Africa. I was fortunate enough to get a copy of The People Shall Govern! from a mentor of mine, Felicia Mings, who had co-curated a project at the Art Institute of Chicago under the same name. In 2019, I had the opportunity to visit Chicago and see these political posters from all over the continent. That sparked my interest related to the unique independence struggles across the continent and the cultural work that was produced in that time period. The exhibit and the book informed my research in very obvious and not so obvious ways. Slowly and slowly, I noticed that I was creating works that reference back to that research and reading process. Sometimes the creative process might be online research, from YouTube, all the way to deep into my Google searches looking for activist archives and these kinds of things. Reference libraries, especially pre-pandemic, was where I would spend a lot of time if I wasn't at the studio, just digging through books.

The Cooper Cole exhibit is called The Volcanic Spine because it follows this eruption in Martinique in 1902, which was one of the most disastrous volcanic eruptions ever documented at that point. The show isn't entirely focused on this incident or this natural disaster per se, but it’s more of a nod to that research process: me learning about the eruption in Martinique in 1902 and thinking about the archive. I discovered that particular incident by going through the Montgomery Collection at the AGO. I was doing an artist residency project. I was looking through this folder of photos, and then after learning about this volcanic eruption, it directed me to research the actual incident. And then months later, this show is built off of that process of researching and reading and digging.

Katherine: For me, that’s real wonder and curiosity at work. Your practice asks us, what else can I know, where will this small citation take me? I really love thinking about art practice as a way to learn, rather than as a means of producing a piece that is intended to be knowable or finished or static. Instead, you are pointing to a learning activity, and that activity sits within the art exhibit. There's a vulnerability there, too. The curiosity is vulnerable because it's about creating work that is unsteady or partial, rather than producing something polished and confident and complete.

Tim: Exactly. The vulnerability of it is exposed, especially because you're sharing these creative ideas with the world. And so you're so worried that the work will be taken out of context or misread. Or someone might think that I'm an expert on a concept, idea or history, when really I'm approaching it as a student. These creative pieces are my notes. You're seeing my notes. True and Functional, my web project, is a manifestation of that. The piece is a collection of my notes that are housed on a website, and people can land there and go through my notes. Sometimes, I go in with that idea of knowing or desiring to know, but I always end up finding out that I have to relinquish that feeling.

Katherine: What you're doing with your notes is a kind of anti-colonial project that turns normative note taking practices upside down. When you were talking about notes and knowing, I was thinking about when I was in a small Ontario public school and often the only black kid in class. And I remember those math classes where you always had to show your work. And there was and is something very punitive about being a black kid in the Ontario public school system–in any kind of education system where it's not open to curiosity and wonder and unknowingness, I guess. To show your notes in that way, you had to prove you did the work; you had to prove you didn’t sidestep the system, you had to measure up. But that was really difficult when the entire educational infrastructure has deemed you either a failure or an impossibility. So, opening up your notes to us kind of rethinks the practice of recording and collecting information that is funneled into a system that so often ignores, in fact, punishes black students, and, at the same time, cannot imagine subversive black note-taking! I would also like to recognize that what you're revealing is that your creative process is ongoing. There’s no overseer clocking your work. I think we could call it a living document–something that will change over time.

Tim: It's funny you say that, because I was one of those kids who struggled with math. And showing your work always felt so scary. Sometimes you didn't even know how you got there. And it's funny, because that's how I feel with my creative practice, which means sitting with vulnerability and letting go of this idea of knowing. It’s like showing my process—like showing your work—but accepting the idea that it's okay to not know, too. When I put the work out there, I hope there are black people who relate to it, who might even know more about some of these ideas and texts, and that this opens up a whole dialogue.

Katherine: Yeah, and so then it invites a conversation rather than a kind of foreclosure or closing down.

Tim: Exactly.

Katherine: But there also is a moment where black artists are also asking us not to be experts. They are asking us, as viewers, to not colonize the work. If you're saying that your creative practice is indicative of a research process and if your creative practice is a way to learn and be a student, then you're also asking those who view your work to engage with it in a different way: as learners, rather than as people who can colonize it and know it completely. So, that's really mind-blowingly cool and insightful, because it understands art as educational and uncertain, rather than polished and complete. Can we talk about the music that you use in the exhibit? I love those pieces. Who are the artists? Are they remixes?

Tim: There's two pieces: “Pelée's Tower” and “No More Accidents,” which are both videos with soundtracks. With “Pelée's Tower,” there's an excerpt from Kamau Brathwaite reading from Born to Slow Horses. There's also this R&B record from this group named Mission. The song is called “Lena.” It was really simple: I just was making these beats, and I took moments from audio and I just really chopped it at a certain point and looped it. I sped it up and took Kamau's voice and then overlaid it. Especially when I'm working with sounds, it really is just finding the parts that fit, it's like puzzling. It's an intuitive process of matching, you know?

That also goes back to thinking about DJing, music and sampling. In “No More Accidents” I take this light, airy melody and the audio and the video is of Brigadier William Akuffo. He's mentioning past traffic accidents and this mundane state decision to change the left-hand traffic to right-hand traffic. I put the audio together with his speech and, again, that's the intuition part. I was thinking about this historical yet bureaucratic moment. Black history highlights struggle, but at the same time, there are these really mundane histories that have nothing to do with white supremacy. Sometimes we are working through something as boring as the change of traffic directions. What if that is a historical moment?

Katherine: You’re also talking about getting through the day and the ordinary tasks that accompany living in this world. So, it is perhaps showing what it's like, within that context of violence, to have everyday conversations and to live in worlds that aren't always punctuated with brutality. Sometimes, just getting through the day is an amazing feat!

Tim: And sometimes the liberation struggle is not necessarily obvious.

Katherine: I think that's important to sit with, because, speaking with black visual artists, I have noticed some curators complaining that the artist’s work, their black art, wasn't violent enough, or it wasn’t black enough. They really wanted to see black people in chains. So, if you want to center, say, black quietness and elegance and love as, to use your term, a meaningful or everyday historical moment, you may not be invited to exhibit your work. And still, black artists press on, showing layers of black livingness as aesthetic practice. This kind of vibe is at play in your work, because I see you subverting and navigating the complex demands of curators and the viewers that really want to see a spectacle of violence.

Tim: Exactly. I also like the idea of pacing and taking people through a story and a narrative so that it is not a singular or flat representation but an uneven or fragmented visual and sonic experience. And you can create breaks for your audience. As a black viewer, there are moments where we want or need a break from the brutality. This is not to dismiss racial violence and anti-blackness, it's more just thinking about how our experience is varied and working out how we situate ourselves differently in this world and also what it means to pace ourselves.

Katherine: Pacing ourselves might give us time to invent or reinvent new worlds. So, in the spirit of Richard Iton, what are you listening to right now?

Tim: What am I listening to? I’ve been listening to KeiyaA, who makes really beautiful music. UK based punk group Big Joanie, a lot of underground rap, Smiley from Toronto. I've also been listening to a lot of South African jazz, between the 1970s and 1980s, like Johnny Dyani and Witchdoctors Son. So that's been really cool, especially when I'm in the music making process and thinking of samples. I've been going there a lot, discovering artists along the way.