The breakdown of the political economy and the means of value production have led to cultural and ideological confusion about what is valuable—and the resulting vacuum in consensus has positioned eliminationist rhetoric as a convincing solution. Debates over who speaks, who is heard, and who is respected are debates about who is valued. The debates turn vicious because they end by answering the question: who society is willing to lose? As Covid revealed, we are willing to lose more people than ever.

It isn’t surprising that eugenicist policy is trending alongside increasing commitment to austerity governance. The centrist majority can no longer unite under the security the political economy once afforded them. Now those centrists—after decades of predation—find themselves becoming prey.

New commodity forms such as NFTs and crypto insist that the world is now pure exchange value, meatless data ricocheting in a frictionless ouroboros while global shortages in food, fuel, and housing continue unabated. The urgent desire for newly minted asset classes is just people looking to be rescued from the very market that has produced the crisis from which they seek to be insulated.

The saying goes that money talks, while wealth whispers—right now both are inflected with the anxiety of loss. By the time “supply chain issues” was a meme phrase, around the time strip clubs observed that we’re in a recession, and before the Johnny Depp trial provided the coda to any perceived social-media-facilitated culture war wins, targets had already been locked.

We’ve reached the expiration date on the neoliberalism and austerity that Western democracies long relied upon to maintain a mask of civility on centrism’s fascist values. Market capitulation was never a sustainable form of statecraft; the consequences of its failures have increased in range.

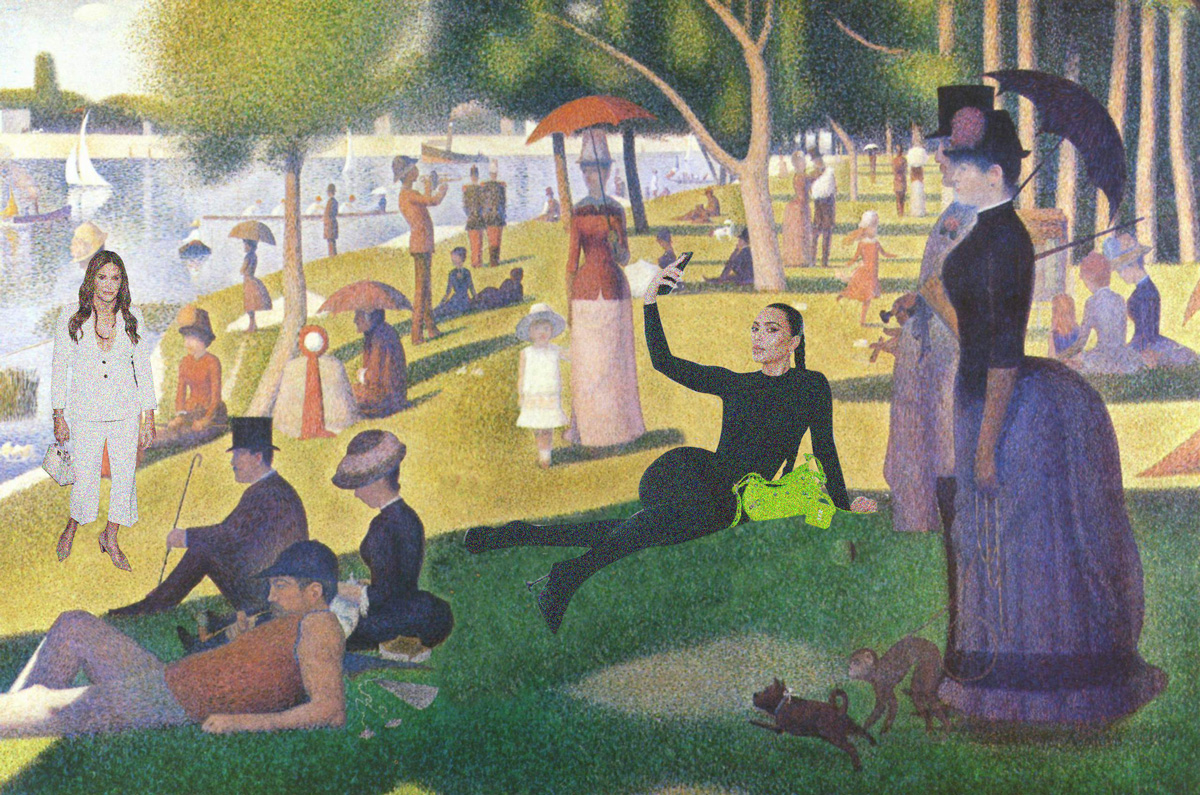

“Assets” asks what will be valuable, not just in our current crisis, but fifty years from now. Half of the issue looks at the privatization of public space. The remaining issue interprets newly valuable commodities.

In “Champagne Wishes and Crypto Dreams” Patrick McGinty reviews the recurring tropes of crypto-memoirs, and what stories of people who risk it all have in common. Then, in “Laundering Bodies,” physician-scholar Mike Gallagher analyzes the rise of bioethics as a distinct and highly privatized medical field, showing how “triage guidelines help assuage the guilt of caregivers faced with impossible decisions.” Elias Rodriques and Clint Williamson’s piece, “Organized Plunder,” describes how some US cities make up for lost income with fines and forfeitures, and, in doing so, turn their own citizens into assets.

“London (Poverty)”—the opening of Aurelia Guo’s new book, World of Interiors—contextualizes London’s financialized housing market with a cultural history of the eighties, the decade in which both she and neoliberalism were born. “Prefab Freedom” by KT Thompson analyzes how skyrocketing ATV usage produces an experience that validates whiteness as an asset. In “Can’t See the Wood for the Trees,” Malcolm Sanger asks whether trees are worth more standing or chopped down as wood; his analysis ranges from Marx’s analysis of wood theft to carbon credit programs. Mason Wong’s “In The Mood For Loss” shows how the financialization of Hong Kong facilitated China’s authoritarian takeover.

This issue’s interview is with Xine Yao, the author of Disaffected: The Cultural Politics of Unfeeling in Nineteenth-Century America (2021). TNI managing editor Charlie Markbreiter talks with Yao about how dissociation is racialized, classed and gendered. Sometimes, the way society is ill-equipped to see you provides some shelter from the consequences of a hostile gaze. And lastly, in “Mall Gothic,” Anna Aguiar Kosicki looks at the rise and decline of the mall, which they link to how the Midwest was developed since its inception. And, lastly, “Baby Heist” by Andrew Lee shows how transnational adoption is used to justify empire.

The old world is dying; the new world is trained to kill. Who survives is increasingly aligned with what they’re fighting for. In examining the concept of “assets” as a flashpoint of decline management, we hope to clarify what holds value when valuation systems disappear.