The hermit crab lives in pursuit of a bigger, better, shell

The World of Interiors (1981–present), The Glossy Years (2019), ‘On Contradiction’ (1937), Hampstead, Golden Eighties (1986), the HIV/AIDS epidemic, gentrification, displacement, migration, the laws of homelessness, vagrancy and lewdness, Margaret Thatcher/Ruth Ellis, Anna Nicole Smith, the functions of the body (sleeping, eating, sex, urinating, defecating, changing clothes), the vulnerability and disgustingness of the body, the Great Chinese Famine, the post‑1980s generation, Sesame Street (1969–present), Piccadilly (1929), “The Getting‑By Years.”

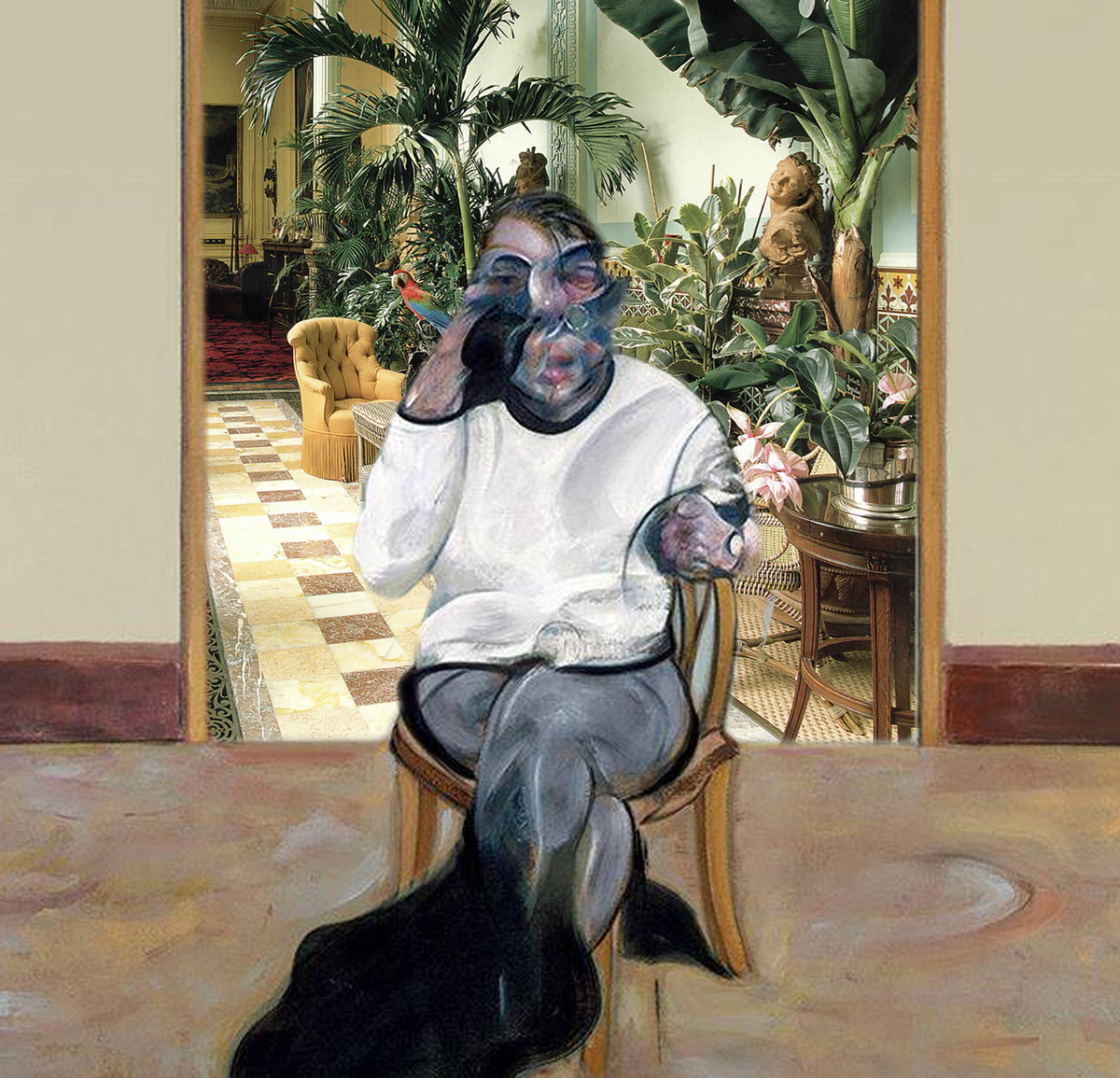

▼

The World of Interiors was first independently published in London in 1981. Known originally as Interiors, the publication was headquartered above a florist’s shop on Fulham Road. Besides being the year in which Prince Charles married Princess Diana, 1981 was the year in which a rare lung infection, a sign of catastrophic immune deficiency, was first reported in five previously healthy gay men in Los Angeles. The 1980s were also the beginning of the period remembered as The Glossy Years in the 2019 memoir of that title by Nicholas Coleridge, the outgoing chairman of Condé Nast Britain, on thirty years spent working for the company spanning the “golden period” in which “ad revenue and circulation climbed year after year and editors brimmed with creative gusto.”

Purchased and rechristened by Condé Nast Britain in 1982, The World of Interiors was a desirable acquisition for the magazine portfolio begun in New York by the businessman Condé Nast at the start of the twentieth century. Beginning with the acquisitions of Vogue in 1909 and Vanity Fair in 1913, Nast’s portfolio was the first of its kind, bringing into being the high‑end glossy as we know it today. At a time in which periodicals, first associated with professions, were expanding to address less specialised audiences, Nast’s innovation was to create “class publications,” magazines that “aimed at a well‑defined socioeconomic group”: Nast recognised in 1915 that business success lay in conspiring “not only to get all their readers from one particular class to which the magazine is dedicated, but rigorously to exclude all others.” As the journalist Kyle Chayka writes in his review of Susan Ronald’s 2019 book Condé Nast: The Man and His Empire, Nast’s dual ambitions to establish himself in Manhattan high society and to build a media empire were “interdependent and mutually reinforcing: Who else but a peer could tell the elite how to act, what to like, and what to buy?”

From its beginnings, Interiors stood out from more established “shelter magazines” focusing on homemaking, furnishings and décor from a more practical standpoint, including the existing Condé Nast title House & Garden. Born in London, Interiors’ founding editor Min Hogg was the daughter of Sir James Cecil Hogg, physician to the Queen. Publishing unprecedented pictures of Buckingham Palace’s private quarters in its first issue, Interiors reflected Hogg’s access as well as tastes. Preferring genteel aesthetics over commercial and professional ones, Hogg favoured a decorating style that was “cluttered, ancestral, simple, eccentric”: The World of Interiors coined the term “shabby chic.”

Showcasing seemingly “every facet of the decorative arts and crafts over the centuries,” The World of Interiors features images of “dusty attics, flaking frescoes, crowded shelves, worn carpets, the kitchens of the schloss… the potting shed of the palazzo.” The magazine had only two editors for almost forty years: its founding editor Hogg until 2000, and then her protégé Rupert Thomas, replaced in 2022 by Hamish Bowles, formerly editor‑at‑large at American Vogue. My August 2021 print copy promises features on “a Neoclassical gem in Piedmont, with Mongiardino interiors” and on “Chafarcani, the patterned linings of 18th‑century Provençal clothes.”

For many years, I have struggled to piece together writing on housing, hoarding and homelessness, gathered between moving house six times in seven years, between Melbourne and London. Perhaps the writing will come together through the pages of “shelter magazines.” What questions about shelter, exposure, shame, pleasure and freedom will I attempt to answer in these pages?

Between shelter and exposure, there is the space of provisional, precarious and irregular housing, negotiated with other people who want or need shared housing. In the lead‑up to the 2019 general election, I reflected on the years I had spent in London since arriving in March 2016, three months before the Brexit referendum. The first London I came to know was gentrifying South London; later, in the years after the 2012 Summer Olympics, I came to know gentrifying East London. Between 2016 and 2020, I lived in a series of sublets and shared flats, including a room in a terrace near Queens Road Peckham Overground station, a room in a run‑down Camberwell terrace, and a room in an ex‑council flat in De Beauvoir Town, part of a large block of council flats off Kingsland Road.

All of these flats were damp, grimy and overcrowded. They all had peeling linoleum floors and mould in the kitchens and bathrooms, and they were all cluttered with the assorted detritus and belongings of long‑departed flatmates. These qualities made the flats similar to flats where I had lived in Sydney and Melbourne, cities that are also full of dilapidated, overcrowded terrace housing. London housing was different in that London winters are colder, darker and damper. In London winters I often visited the Finnish sauna in the basement of the Finnish Church in Rotherhithe. This was a rare place I felt adequately clean and warm.

Living in poor conditions has been the norm among most people I know for most of my adult life, at least in large cities like Sydney, Melbourne and London. Living in a cheap room in a grimy flat, discovered by word of mouth, has been commonplace. For some of the people who share housing in these circumstances, it is an optional form of sociability applicable only to young adulthood. For others, sharing housing in poor conditions is a necessary form of survival that has a prior beginning and that does not have a clear end. When living in close proximity with others, it helps to forget who belongs to what group and to what degree.

I left “home” at seventeen; “home” is a place to which I can’t return. The places I lived between 2007 and 2020 include a series of single dorms in student housing in Canberra and a single‑room occupancy in Sydney. I lived “alone” in single rooms for seven years, before living in rooms in flatshares for six years, without counting periods of even less regular housing, including sleeping on a couch, or at a hostel. For six months, as an exchange student in Maastricht, I lived in a shared room inside a wing of a hospital. When I returned to law school in Canberra, in a shortfall of student housing, I drifted between friends’ couches and a friend’s family home. I had known housing upheavals throughout my childhood. I first came to know secure housing relatively late in my adult life.

In “Life at the Corner of Poverty and Abjection,” the legal theorist Libby Adler connects modern American laws criminalising homelessness to their historical origin in late-medieval and early-modern English vagrancy laws. In a crumbling feudal order, threatened by the rising wages and increasing mobility of labour in the wake of depopulation by the Black Death, these laws had served the economic purpose of binding labourers to their agrarian responsibilities. These laws reflected social as well as economic concerns: they cast migrants as social deviants and likely criminals. In the words of the legal scholar Margaret K. Rosenheim, “The unattached stranger lacking visible means of support was seen as a predator, a threat to public safety.”

A restricted class of the “impotent poor” were entitled to limited forms of poor relief through local parishes. The rest of the poor were forbidden to refuse work, to bargain for wages, or to leave their local areas through vagrancy statutes that sought to tie workers to their jobs. Citing work by Rosenheim and the legal scholar Caleb Foote, Adler writes that the Elizabethan poor law of 1601 reiterated this “principle of local responsibility” for the poor and also emphasized “the principle of settlement and removal”:

The mid‑seventeenth‑century “Law of Settlement” provided additional administrative mechanisms for “removal,” largely to address migration to urban areas. Cities did not wish to be “burdened with the annoyance and economic liability of foreign paupers and idlers.” Such migrants could be not only removed, but also punished.

Adler criticises the importance that has been accorded to a right to privacy in gay law reform, noting the over‑representation of queer people, particularly young queer people, among the homeless. Unable to benefit from legal protections accorded to privacy, of which they have none, queer homeless youth are vulnerable to the criminalisation of homelessness in general, and to criminalisation more specifically under laws forbidding ‘lewdness’ and indecent exposure of the naked body. Adler, quoting the legal philosopher Jeremy Waldron, writes that

If everyone had “access to a private home, activities deemed particularly appropriate to the private realm––activities like sleeping, lovemaking, washing, urinating, etc.––could be confined to that realm. Public places could be put off‑limits to such activities, and dedicated instead to activities which complement those that citizens ought to perform in their own homes”. . . [but] the homeless “have no alternative but to be and remain and live all their lives (all aspects of their lives) in public.” For such persons there is an unavoidable failure of the complementarity between the use of private space and the use of public space.

In the 1980s, the decade in which I was born, I search for the world in which I was born. In the July 1987 issue of Marxism Today, following the third consecutive electoral victory––and the second landslide victory––of the Conservative Party in Britain, the sociologist Stuart Hall wrote that “the electorate is thinking politically, not in terms of policies but of images.” Hall argued that the Labour Party had underestimated the importance of political identities and identifications, failing to offer an imaginative and ideological alternative to Thatcherism. The feminist scholar Jacqueline Rose quotes Hall in her essay on Margaret Thatcher and Ruth Ellis, the last woman to be executed in Britain. Born in 1925, a year before Thatcher, the nightclub hostess Ellis was hanged in 1955 for the fatal shooting of her boyfriend David Blakely, a wealthy socialite and race‑car driver. In a footnote to the essay, Rose notes certain socio‑economic parallels between the two women:

Ellis’s father came from a successful and respected middle‑class family which had made its money out of weaving. His own father was a musician (a cathedral organ player) and he himself was a cellist and cinema musician until the advent of speaking pictures drove him down the social scale into unemployment, and then work as porter, caretaker and chauffeur. Her mother was a Belgian‑French refugee. Ellis could be said to have tried to make her way as a woman back up that scale by working as a model and then a club hostess. In that post‑war period which was so decisive for the two women, therefore, Ellis had strong aspirations to social mobility not dissimilar in form, although unlike in trajectory, to Thatcher’s own.

I search for a relation between womanhood, wealth and poverty in the petit bourgeois trajectories of Ellis and Thatcher. Rose notes, also, the “same iconography of meticulous artificiality and precision’ of personal appearance in press images of Ellis and of Thatcher.” Of Thatcher’s relation to her femininity, Rose writes,

We can only note the contradictions: from denial (“People are more conscious of me being a woman than I am of being a woman”), embracing of the most phallic of self‑images (the iron lady), to the insistence on her femininity as utterly banal (the housewife managing the purse‑strings of the nation).

Margaret Thatcher and Ruth Ellis meet as “victim” and “executioner” in Rose, who argues, after the psychoanalytic philosopher Julia Kristeva, that Thatcher, a proponent of capital punishment whose 1983 electoral success could partly be credited to the Falklands War, was able to “get away with murder” as a woman, a subject whose capacity for violence is at once embraced and disavowed.

I read Rose in the Hampstead apartment that I share with my husband. We live on the street that ends in The Magdala pub, outside which Ellis shot Blakely. Her 1955 hanging bereaved a husband, a son and a daughter. Both her husband and her son, ten years old at the time of Ellis’s death, later died by suicide, in 1958 and 1982 respectively; her daughter, three years old at the time of her mother’s execution, was raised in foster care after her father’s suicide. Described in an area guide from the estate agency Knight Frank as populated by “intellectuals, thespians, artists, architects and the wealthy,” Hampstead is where I have settled. “Hampstead has more millionaires within its boundaries than any other area of the United Kingdom.”

In Hampstead, I search for a relation between family and violence. In Hampstead I watch Chantal Akerman’s 1986 film Golden Eighties, also known as Window Shopping, an exuberant musical in the Technicolor tradition of MGM. Set within the confines of a Belgian shopping mall, Golden Eighties takes place in a brightly coloured world into which Jeanne, now a married boutique‑owner with an adult daughter, has emerged after surviving Auschwitz. Immaculately groomed, dressed and made‑up, Jeanne sings, dances and gently resists the advances of an ex‑boyfriend, an American who was a soldier stationed in France during World War II. Of life in the Toison d’Or (“Golden Fleece”) shopping mall, the filmmaker and curator Adam Roberts writes,

everything is for sale, everything is desirable if beautifully presented in a shop window . . . This is after all the 80s––golden or not, depending on your outlook. The film also makes it very clear that the 1980s are a time of economic difficulty––where businesses are failing, where customers are scarce, where only the fittest will survive – and there is no alternative world view on offer. Everything is for sale, if only someone would buy.

Among the “intellectuals, thespians, artists, architects and the wealthy,” Hampstead’s residents include generational survivors of Jewish displacement from Europe. In Hampstead I think about survival when we receive letters addressed to a former resident of our apartment, an elderly German‑Jewish woman who arrived in England on the Kindertransport. A British state initiative in response to political pressure to rescue Jewish children from Nazi persecution, the Kindertransport was also a policy of family separation and a concession to anti‑immigrant sentiment. Many child refugees of the Kindertransport would emerge from the war as the only surviving members of their families. Dispersed in Britain through foster families and group homes, older children performed domestic and agricultural work. Despite some volunteering for the British military on reaching eighteen, in 1940 Kindertransportees were caught in a storm of “Fifth Column” hysteria. Over 1,000 were interned on the Isle of Man and other sites, while others were deported to Canada and Australia, ostensibly to prevent them collaborating with the Nazis. What lives did survivors of twentieth‑century atrocities build in their aftermath? In Golden Eighties, Jeanne must negotiate shifting family dynamics and keep a struggling boutique solvent after Auschwitz.

In Hampstead, I search for the meaning of poverty in the books that I borrow from the library. In Untimely Beggar, Patrick Greaney writes that it is a “simple, well‑known fact” that “in the nineteenth century, the poor were associated with power”; that in their “labour power and revolutionary potential,” Europe’s nineteenth‑century poor embodied “productive and destructive forces.” I search for meaning in the London‑centred world economy of the nineteenth century, built on the “system of private enterprise and competition that arose in the 16th century from the development of sea routes, international trade, and colonialism.” The rise of the system “had been facilitated by changes in the forces of production . . . the adoption of mechanization, and technical progress. The wealth of the societies that brought this economy into play had been acquired through an “enormous accumulation of commodities.”

Famously in Marx, the expansion of capital is interdependent with the growing impoverishment of the working class: “Accumulation of wealth at one pole is, therefore, at the same time accumulation of misery, agony of toil slavery, ignorance, brutality, mental degradation at the opposite pole.” Marx cites the eighteenth‑century Venetian monk Ortes, who regards the antagonism of capitalist production as a general natural law of social wealth:

In the economy of a nation, advantages and evils always balance one another (il bene ed il male economico in una nazione sempre all’ istessa misura): the abundance of wealth with some people, is always equal to the want of it with others (la copia dei beni in alcuni sempre egualealia mancanza di essi in altri) . . .

In Hampstead I read the glossy magazines that have fascinated me since I was a child. I read about the products that I can buy. In Crap: A History of Cheap Stuff in America, the historian Wendy Woloson writes of the expanded availability of consumer goods in nineteenth‑century America, lessening the burdens of ownership and making available the pleasure of acquiring new things, “a historical shift that meant the public no longer had to make do with just a few things that would have to last a lifetime.” This is the genesis of “crap,” “typically low-priced, poorly made, composed of inferior materials, lacking in meaningful purpose, and not meant to last.” Of nineteenth‑century tenement dwellers, Woloson writes that although they lived in “filthy, damp and dismal conditions . . . [they] nevertheless were able to ‘crowd’ their mantelpieces with cheap figurines.”

In Hampstead, I think about survival, displacement and dispossession, including in the basic sense of lost and forfeited belongings. When I think about the twentieth century, I think about the consumer iconography that I have known since childhood, advertising the expanded range of consumer goods available, at times affordable, for all to buy. I think about consumer goods and the ways in which they may replace lost belongings. I think about their accumulation in permanent and in provisional homes. I think about the clothing, cosmetics and accoutrements needed to produce a feminine appearance, and how sexual desirability represents one of few paths to survival, if not social mobility, for many women.

I search for a relation between womanhood, wealth, poverty and consumer products. Does womanhood enrich or impoverish? Can one escape poverty through womanhood, as if poverty were a place, as if poverty could be left behind? In a 2017 essay on the celebrity Anna Nicole Smith, the journalist Sarah Marshall describes poverty as a “legacy.” Marshall’s use of the term suggests that one can inherit poverty from one’s family, much as another person might inherit wealth or property. The 1993 Playmate of the Year and Guess jeans model, then aged twenty‑six, gained infamy in 1994 after marrying her boyfriend of three years, the eighty‑nine‑year‑old billionaire oilman J. Howard Marshall.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1905 into a distinguished family which had made a fortune in steel, by the time of his marriage to Smith Marshall had been a “master of every aspect of the oil business, from exploration to marketing, from the courtroom to the government” for over five decades. The part‑owner of Koch Industries and one of America’s richest men was reported to have been left “crying in his wheelchair” when his bride departed for a photoshoot after their wedding ceremony. Later allegations against Smith included that she once left Marshall outside in heavy rain. Public ridicule of Smith’s marriage offered an outlet for the discomfort of witnessing a powerful man’s vulnerability.

The 2002 E! reality television series, The Anna Nicole Show, filmed in the last decade of Smith’s life, took part in this derision. At the same time, the series documented Smith’s legacy. This legacy was one of poverty from her parents, not riches from her husband. Marshall died thirteen months into their marriage, and his estate remained bitterly contested almost two decades after his death. Smith’s mother, Virgie, had given birth to Smith at sixteen. Her marriage to Smith’s father ended after he pleaded guilty to the statutory rape of Virgie’s ten‑year‑old sister. By the time she was an adult, Smith remained “almost illiterate.” As Sarah Marshall writes, Smith’s struggles with pain, addiction and ageing, with legal and family troubles, were part of a family legacy of “poor health, disability, abuse, and helplessness.”

Family appears as the personification of poverty in the episode of The Anna Nicole Show in which Smith’s cousin Shelly appears at Smith’s doorstep, her own camera team in tow, to ask Smith for money. Shelly has no teeth, having lost them since they were last repaired at Smith’s expense. Smith promises another fix. In a separate episode, Smith has twenty crowns placed over her own teeth: she has sustained lasting nerve damage from grinding them due to stress. Smith’s legal battles were not confined to those fought over her late husband’s estate against his sons. Smith also faced allegations from one domestic worker that she neglectfully underfed her infant daughter. From a separate domestic worker, Smith faced allegations of sexual harassment. Smith was said to have repeatedly propositioned her and to have told her she loved her.

Who was Anna Nicole Smith, born Vickie Lynn Hogan on 28 November 1967, in Houston, Texas? She once reminded the cameras that she had married, become a mother and divorced, all by the age of eighteen. In her years working as an exotic dancer, Smith dated women as well as men. Prescribed extensive drugs for post‑surgical pain and epileptic seizures, Smith died of an accidental overdose in a Florida hotel room in February 2007, aged thirty‑nine, five months after the drug‑related death of her twenty‑year‑old son. She left behind a five‑month‑old daughter.

In Hampstead I think about parenting. In the privacy of my home, I accumulate products for “sleeping, lovemaking, washing, urinating, etc.” In the privacy of my home I examine my teeth in the mirror on the wall. I think about dentistry. “I only started going to the dentist in my twenties,” Smith tells the cameras. “I hate the dentist because they hurt me.” In Smith’s struggles, I think about the ways in which taking care of one’s appearance can both converge with and diverge from taking care of one’s more basic needs. In May 2012, the cultural theorist Lauren Berlant wrote of their mother’s death,

My mother died of femininity . . . In her late teens she took up smoking, because it was sold as a weight-reduction aid. When she died she had aggressive stage 4 lung cancer. In her teens she started wearing high heels . . . Later, she had an abortion and on the way out tripped down the stairs in those heels, hurting her back permanently. Decades later, selling dresses at Bloomingdale’s, she was forced to carry, by her estimate, 500 lbs. of clothes each day. Shop girls, you know, are forced to dress like their customers. They have to do this to show that they understand the appropriate universe of taste, even while working like mules in that same universe, carrying to their ladies stacks of hanging things and having to reorganise what their ladies left behind on the dressing room floor. She liked this job, because she liked being known as having good taste. These tasks threw her back out anew, and the result of this was an overconsumption of painkillers that ultimately blew out her kidneys. She had to go onto dialysis . . . more comically, she had two fingers partly amputated because her nails got infected by a ‘French wrap’ gone wrong, and she was too ashamed to tell anyone about it, numbing the pain of infection with Anbesol, which she had also used for many years to avoid going to the dentist.

For the first time living in a permanent home, for the first time I accumulate “abundant” and “varied” clothing. I recall the historian Howard French explaining how “cotton grown by enslaved people in the American south helped launch formal industrialization, along with a second wave of consumerism. Abundant and varied clothing for the masses became a reality for the first time in human history.”

In Hampstead, I no longer wear the same black t‐shirt, shorts and sneakers year‐round, the “uniform” of years of poverty. Now I have changes of clothing: for seasons, for occasions, for the sake of fashion. As I get changed, I examine myself in the mirror. I think about Mao Zedong’s 1937 essay “On Contradiction”: “The law of contradiction in things, that is, the law of the unity of opposites, is the basic law of materialist dialectics.” Marx writes of the interdependent and mutually constitutive nature of the bourgeoisie and proletariat; Mao writes of their unsettling capacity for interchangeability.

In “On Contradiction,” Mao espouses a philosophical position of materialist dialectics, a world view opposed to that of those he terms the “metaphysicians, or vulgar evolutionists,” who “hold that all the different kinds of things in the universe and all their characteristics have been the same ever since they first came into being,” ascribing social change to external factors like climate and geography. By contrast, in materialist dialectics, Mao writes, “The fundamental cause of the development of a thing is not external but internal; it lies in the contradictoriness within the thing. There is internal contradiction in every single thing, hence its motion and development.” He writes that “opposites possess identity, and consequently can coexist in a single entity and can transform themselves into each other . . . But the struggle of opposites is ceaseless, it goes on both when the opposites are coexisting and when they are transforming themselves into each other, and becomes especially conspicuous when they are transforming themselves into one another.”

[essay continues in book]

***

World of Interiors by Aurelia Guo was published April 2022 by Divided Press.