Youth is provisional. The stuff of market pictures, loans and auctioned prospects, finance and gentrification, enhancement and anxiety. Or else it is, away from the metropole, the material of the drain, which is to say that either youth itself is drained, or the nation-state is drained of the youth: it is either unemployment or remittances.

If youth is ever fatally confrontational, they say it is misdirected will, gone too soon. It is without history.

There is a delay before the learned persons of an era adequately register the proclamations made by the youth. Ten years ago, Alain Badiou made a distinction between “immediate riot” (race riots in France and UK) and “historical riot” (“Arab Spring”). To make this kind of distinction is to miss the writing on the wall for the dirt that the inscriptions were made with. If we wait long enough for the books, we may find out whether the feminist uprising currently underway in Iran is historical, or not.

Between the romance of the moment of revolt and the bitterness of loss is a tragic bookkeeping. The time of the restoration, after political defeat, is a time of tallying and making lists if it is not to be a time of surrender. This form of enumeration is eulogistic, and must start from an account of both those who are made to depart and to disappear.

+

Here is a list of two youths who brought torrents with them when they left the world of the living, by choice or by force, and whose deaths have become generational plot devices: Mahsa [Kurdish name: Jîna] Amini (1999-2022) and Mohamed Bouazizi (1984-2011). Between these two, chronologically, there is a third: Sarah Hegazi (1989-2020), the Egyptian writer and activist who was imprisoned for three months and tortured after waving a (Western) rainbow flag at a Mashrou’ Leila concert in 2017. This is a very partial list.

All three are young, but I grant that I am using youth in a loose and noncommittal kind of way, more to indicate nascent political subjectivity than anyone’s age. Some struggles, because they are not thought to be anchored in the wage relation or the nation-state, are prone to be perceived narrowly through their particular identity markers, those by which they are known and targeted.

Spontaneity begets misunderstanding and dismissal. A riot is direct, interpersonal, and fully spontaneous.

Putting aside any identity markers that Hegazi and I share, she was also a communist, and excusing the sectarianism, she was a revolutionary socialist. On the eve of the uprising in Beirut, October 19th, 2019, she was in Ontari giving a talk about the lessons learned from the Egyptian uprising, on the different odors of counterrevolution, to a Sudanese audience whose country of origin was then ablaze as well.

She, the atheist lesbian, could not resist saying that any revolutionary alliance with political Islamism will not hold, because that alliance will be betrayed. It is a telling reversal, given that political Islam repeatedly claims to be betrayed by queers and feminists and other objectors in favor of the lifestyles of empire, in the continuing post-9/11 world. To borrow the language of world-systems theory: it is a matter of accepting that there is currently one world-hegemon, the United States, which does not in any way imply that other states, like Russia or China, cannot engage in imperialist expansion, or that dissent against enemy regimes to the United States implies implicit defense of the hegemonic world order. Any ongoing struggles in the world-system dominated by a waning hegemon are warped by the gravitational pull of that hegemon. Then there is no surprise that barely a few days into the uprising in Iran Vice President Kamala Harris met with Iranian human rights activists, or that the Israeli Foreign Ministry launched a video campaign titled Israeli Women Stand with Iranian Women. We have to continue insisting that this speaks more of empire and the world-system than it does of the protests in Tehran or Damascus or Beirut.

I myself had to leave Beirut soon after the uprising. As I type on a computer in Berlin—among German “Antideutsche” punks who have such merited and unmerited distrust of organized movement, of an Anti-Semitic immigrant who will dredge up what preceded the unification myths, who in November had a German-translation launch event for a 1983 book titled Von Moskau nach Beirut: Essay über die Desinformation which retraces the alleged eruption of the figure of the “professional Palestinian ‘oppressed’” and backlash against Israel during its invasion of Lebanon in 1982, back to the Six-Day War (Arab Naksa) of 1967 and into the student movements of 1968, as though 1982 was not the year of the massacre of Palestinian civilians in their beds in Sabra and Chatila—my vision frays at the edges and I have to squint. I have just returned from a Western Union shop, and I have myself become remittances. I wonder, did Sarah Hegazi, in her exile in Canada, ever send back remittances to her family? At the Western Union, the currency exchange rate is always adverse and I am delivered into the confines of the following thought: if not I or we, then those friends of friends from Cairo or El Mansoura who had come to Berlin in the last decade after their incomplete revolution and who had also died in exile, who were sent back to their family plots or buried in the Neukolln cemetery after unexplained causes, due to something about Egypt, that ancient machine for humor and pop culture export—do they not contain within them a Hegazi? Or the cousin of mine in Lebanon who drove around on a motorcycle for years delivering sushi platters, whose motorcycle was stolen last week, who is constantly becoming unemployed, does he not contain in him a Bouazizi? I am not trying to say that there is still a quotient of solidarity, that panacea, that must be proclaimed. Rather I am, both more humbly and more delusionally, trying to say that every one of those persons, like every remittance and commodity, contains within them the whole of the others, the thrumming current, a many-headed Hydra that is neither identical nor equal to itself.

This I can say in prose, in English from a safe distance in Berlin, like a poet without many great stakes, but I don’t think it would be very easy to explain this to, say, the sitting elders of the Communist Party in Beirut. It is not that the youths have rejected organization, but that existing organization has, more often than not, repelled the youths. But that also cannot be fully true, or should not continue to be true: Sarah Hegazi was a founding member of the democratic socialist Bread and Freedom Party, and organization is not just a question of the party.

Between spontaneity and organization, there are forms which flash by and must be stubbornly recorded by any historian of the immediate. A text written by an unnamed Iranian protester under the name L, titled “Women Reflected in Their Own History” and published in the first weeks of the uprising in Iran, attempts that formal work of the historian of the immediate, she who reaches for language to approximate the appearances of struggle that are not easily contained by pre-existing signifiers such as worker’s strike, even if the workers have rallied to support the women in the streets. In the text, L described a particular logic of the feminist riot, whereby groups of rioters flock around particular situations, such as waving a headscarf or burning a hijab, an insurrectionist dynamic which is very different from the demo or march. She speaks of a “figural desire,” a form of mimetic contagion, experienced by herself and comrades upon catching sight of other women facing state violence. On the street, the body is warm and numb and can take a police baton. “Historical syncope” is the term she uses for the pause in history felt upon witnessing another body in the face-off. The riot is always within history, which is to say a lot, and not nearly enough.

At the time of writing, more than 18,000 individuals have been arrested and more than 500 killed by Iranian regime forces since the start of the revolt in September 2022. It may be recalled that after the Islamic regime reaped the fruits of the 1979 revolution in Iran, the eighties became a decade of extrajudicial killings of leftists in the region, fractally mirroring the waves of anti-communism initiated by US-aligned governments across the 20th century. In Lebanon, towards the end of the civil war in the late eighties, Hezbollah partook in assassinations of Communist Party intellectuals, having risen to power as a local paramilitary force bolstered by the ascendant Iranian regime and its policy of “Exporting the Revolution.” We are still living through the dearth created in those years.

But if in Iran it is now an ambivalent dawn, with ongoing executions and mass imprisonment, elsewhere it is far past dusk. After an uprising, there may be a restoration of reactionary power; after a spring there may come the prison. In Egypt, more than thirty-five new prisons have been built since Sisi’s coup in 2013, to house more than 120,000 prisoners, 65,000 of whom are recognized as political prisoners. To make a distinction between a political and a non-political prisoner is to lapse into the diction of the state while attempting to wield the cudgel against it. It is to fall back into drawing a line between deserving and undeserving victim, dissident and criminal, leftist and Islamist. Mahienour El-Massry, legal activist and former political prisoner, has remarked that among Egyptian progressives, there is a division about extending solidarity, between those who say, “against the Islamists always, with the government sometimes” versus others who reverse that to say, “against the government always, with the Islamists sometimes” when the Islamists are imprisoned. Alaa Abdel Fattah—arguably the most well-known of the political prisoners in Egypt, who went on hunger strike for more than six months last year and has not yet been released—wrote in 2016 that it became a narrative battle to get some leftists to accept that the Rabaa el-Adaweya massacre, which took the lives of more than 1000 civilians, the majority of whom were Islamists, was a massacre at all.

Even if the Islamists never owed much to the leftists, the latter, if they are sufficiently abolitionist, must not reciprocate in kind.

+

I’ve heard one question posed often, about why it is that both the art and politics of the slave society of ancient Greece, the epic and the agora, still fascinate and enthrall, notwithstanding the supremacist biases of the disciplines tasked with studying the Hellenics. Some Marxists answer this question by suggesting that the fascination is due to the fact that ancient Greek society was not mediated by an impersonal money-form, but was ruthlessly direct: direct forms of political participation (Athenian democracy), direct forms of subjugation (slavery), directness in aesthetic and literary form (gods and men and women sleeping with each other in the epic). So there is a romantic longing for the direct and interpersonal, or for an agora reachable by way of the eradication of all currencies.

But this remains farfetched. Against an agora (ἀγορά) in space, I am thinking of a syntagma (σύνταγμα) in time.

Syntagma Square, the central square in Athens, was site of the mass anti-austerity protests which began in 2010 following the Greek debt crisis; it is named after the country’s first constitution which was conceded by the German monarch of the Kingdom of Greece in 1884, also referred to as a syntagma. So it is after all a city square, and also that highest, most legitimized form of power: a new state’s constitution is only written after the revolutionary moment has passed.

In semiotics, a syntagma is simply a list where the items, not necessarily in one order, amount to more than their sum. So I’ll say it is a sort of list that begins in the early 2010s, or in the late 19th century.

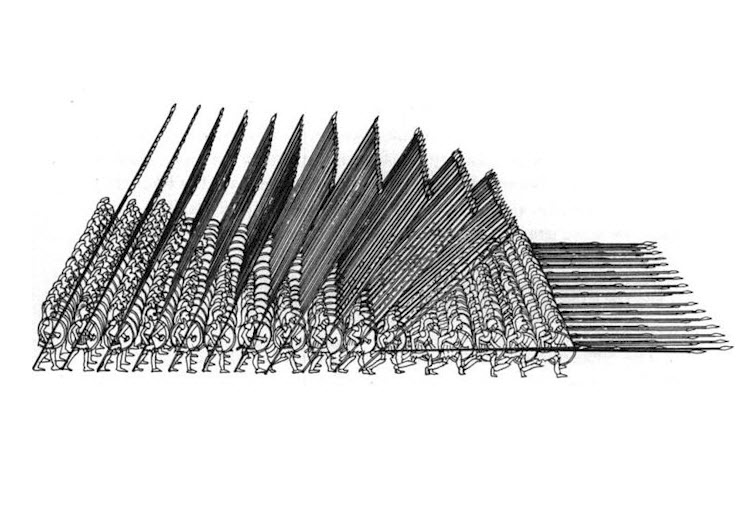

A syntagma is also the most basic infantry unit, armed with spears, in the Macedonian army. If we squint enough, we might see Tiktok videos of the newly-assembled armed units in the West Bank who have named themselves the Lion’s Den, after the 2021 Palestinian Unity Intifada—all of whom are, in the stricter sense, youths.

Of syntagmas in the texts of socialist utopian Charles Fourier, Roland Barthes writes that their “enumerative cumulus” joins together “a very ambitious thought and a very futile object,” intervening “between the domestic details of the example and the scope of the utopian plan,” in this case, an inventory of a burning domicile.

So here we may draw up a tentative list, one that joins the futile subjects of a very ambitious thought: self-immolating man, barely employed street vendor, unemployed racialized surplus, stateless Kurd, Palestinian after Unity Intifada, South queer in North exile, woman burning hijab, political and non-political prisoner—