“The Nisha Chicken Salad” on Weight Watchers’s website bears little resemblance to the salad Nisha Godfrey went viral for in 2022. It is two cups of spinach leaves with three ounces of grilled skinless, boneless chicken breast and an assortment of raw toppings in fractioned quantities coated with a single tablespoon of vinaigrette and a dusting of parmigiano reggiano. But it was never really about the salad.

The popularity of Godfrey’s reaction to the chicken salad from Cleveland’s East 81st Street Deli, with its bed of crunchy lettuce covered in chicken and other toppings smothered in a creamy white salad dressing, was all Godfrey. It was about her personality, her ability to communicate her enjoyment of and satisfaction from the salad between plastic forkfuls: “Y'all better come out here and get one of these… It’s a chicken salad.” One commenter on the original video pinned to the top of the deli’s TikTok page noted that she “said it like a teacher on their lunch break.” Countless others declared that they “trust” her, that her voice and cadence are “comforting.” Audio of her speaking—rubbing over the words “chicken salad,” reminding you of the last thing that really hit the spot—appears on more than 200,000 TikToks, ranging from odes to other chicken salads to pink iPads to butt-accentuating pants.

After being contacted and lowballed by several companies, including Google, Godfrey landed a lucrative brand deal with Weight Watchers to recreate and promote “The Nisha Chicken Salad.” On Weight Watchers’s TikTok account, the video of Godfrey recreating her viral moment with the WW salad is their most watched video (by a very large margin) with 2.8 million views. Unsurprisingly, she is also one of very few fat or Black people shown on the account and even fewer, if not, the only, fat Black woman in any of Weight Watchers’s TikTok videos.

Weight Watchers’s collaboration with Godfrey is one of many examples of how the weight loss industry has worked to adapt and expand their market within a cultural moment that has changed how and why weight loss sells. A new cultural moment with “game changing” weight loss medications that promise unseen levels of profit. A new cultural moment that, if it is to be capitalized on, requires the right tools: Black women.

It is not that Black women have never been invited into the estate that antifatness built. Jennifer Hudson and Oprah Winfrey’s years-long affiliations with Weight Watchers were mainstays of 2010s advertising and, in Winfrey’s case, has led to an eight-percent stake in a company worth millions of dollars. However, the context that new entries to the scene are operating in is a complete departure from the overt fatphobia of the 2010s, as well as the previous collective consciousness around social justice, racism, and oppression. In contrast to the social moment in which Hudson and Winfrey were prominent WW ambassadors, the weight loss industry is presently operating in a post-“body positivity,” post-“racial reckoning” era.

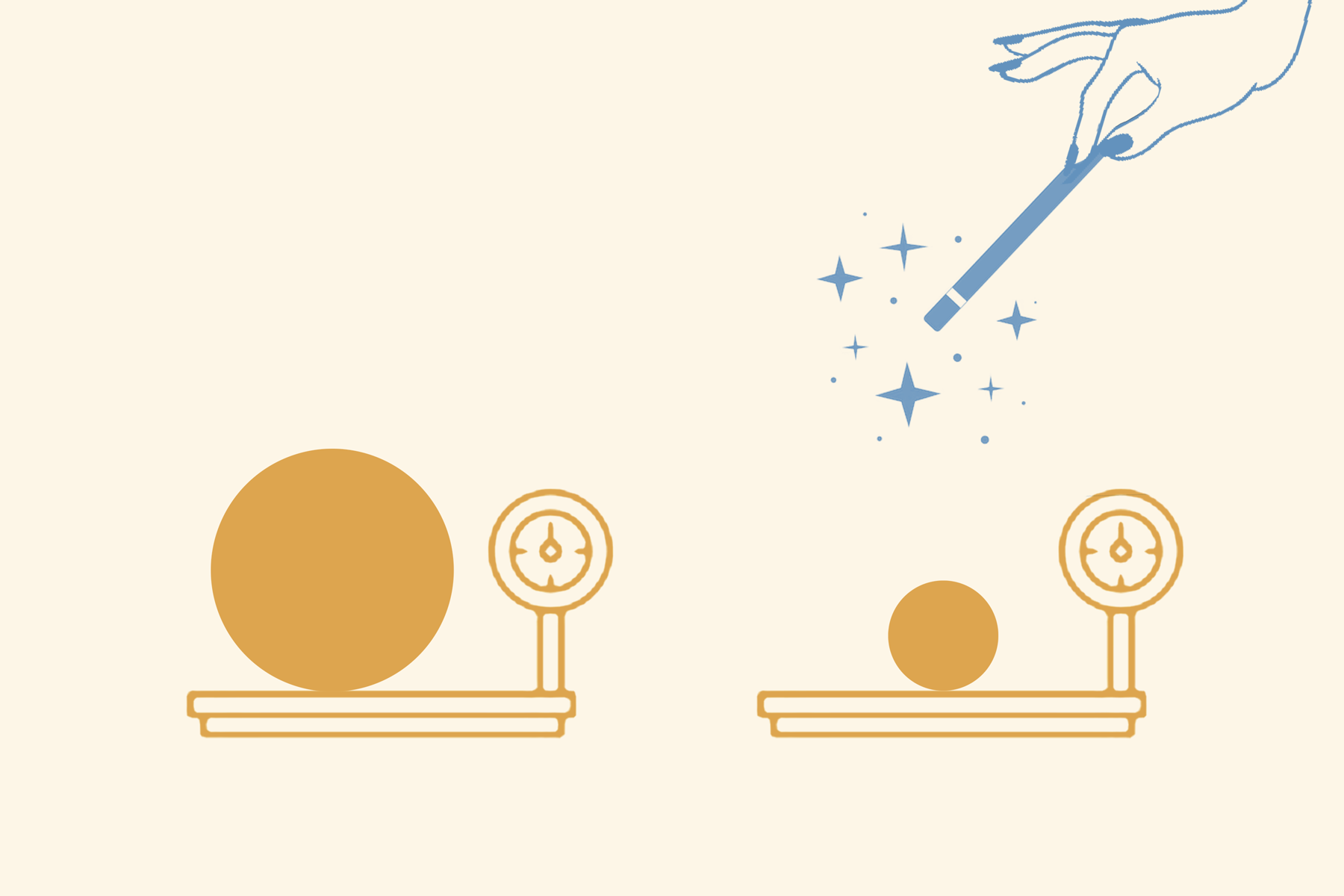

People still want to be thinner, but after almost two decades of corporate slogans about “real beauty” and the mainstreaming of “body positivity,” weight loss products have to be presented with some decorum. Fewer units—inches, pounds, dress sizes—and more nouns—joy, stress, freedom, you. “Wellness*” (*as signified by weight), versus something less friendly, less holistic. This shift is not uniform across all people, but as a fat liberationist, it is obvious that the cultural consciousness about weight loss has shifted . More and more people are concerned with “just being healthy” instead of being thin, even though the wider consciousness about being “healthy” remains synonymous with thinness.

Illustrations with the phrase “all bodies are good bodies” now exist on the same social media timelines as Flat Tummy teas. This is the social moment when Noom’s pivot to being not just a diet app, but “a way to understand yourself better,” meant a reported 400 million dollars in 2020 sales. The foundations of global fatphobia—antiblackness, healthism, ableism, classism, capitalism, etc.—are undisrupted, but our sensitivities have changed.

The summer of 2020, with its protests against the police murders of Black folks including George Floyd and Breonna Taylor was supposed to be a turning point in the US’s fight for “racial justice,”, but the turn ended as soon as the corporate statements were posted and the white outrage died. It was, as NPR’s Code Switch dubbed it, “the racial reckoning that wasn’t.” We’ve settled in a place where Black oppression is uncomfortable, objectionable—and also kind of passé to ignore—for many more people, but not potentially world-breaking. Never world-breaking.

As abolitionist and critical urban theorist Tea Troutman shared in an interview with Black Agenda Report, “waves of spectacular violence, summer uprisings, and hypervisible social justice organizing has increased demand for market-approved work from its radical, leftist counterparts that offer romanticism of Black resistance.” Troutman’s interview includes crucial criticisms of a landscape increasingly made up of state-aligned strategies, “celebrity activists,” and continued defanging of resistance tactics. I have seen this landscape bloom.There is capital (social and otherwise) to be hoarded by reading the right books, feigning proximity to revolutionary action, and publicly pondering—for some parties, for the first time—about what it means to be oppressed.

If awareness and visibility meant the end of oppression, we would be in an unprecedented moment; instead, we are in an ongoing and minimized global pandemic in which the Black, fat, disabled, elderly, poor, and otherwise vulnerable will continue to “fall by the wayside”, dual sacrifices and scapegoats, as dictated by those with the power to preserve our lives. The same neoliberal market logics that gave rise to our hands-off, business-first public health infrastructure are inherent to our evolving but persistent desires to be “in shape,” to be in a state of perpetual self-growth, to be “taking care of ourselves.” But in the absence of true state investment in keeping people alive through comprehensive messaging and social safety nets, the public is forced to offset our “return to normal” with market-sourced tools. The public, reaching for life, for longevity, for survival among the fittest (as dictated by eugenics) has turned its eyes to its physique.

Ozempic, to shareholders glee, arrived right on time.

A 2022 Morgan Stanley Research report (“Unlocking the Obesity Challenge: A >$50bn Market”) predicted that, “with conservative pricing assumptions,” global “obesity” sales have the potential to reach $54 billion in 2030. If the weight loss industry manages to achieve its desired policy changes—most prominently, uniform insurance coverage for weight loss medications—they will have removed one of the most significant hurdles left to mainstreaming these medications in primary care.

The fat activism movement in the US, which has its documented beginnings in the 1960s, is made of a particularly diffuse array of actors who participate in diverse forms of awareness-raising, coalition building, and agitating. (For a record of the movement’s development and significant events, I recommend Charlotte Cooper’s Fat Activism: A Radical Social Movement, which was published in 2016. The development and history of antifatness is beyond the scope of this essay, but I cover them here.). The domain that basically all fat activists engage with, directly or indirectly, is healthcare.

The last place most fat people want to be is a clinical examination room. The question of our medical trauma and mistreatment is in the hows, whens, or to what degrees. This is due to the all-encompassing nature of the existing obesity elimination paradigm which shapes fat and not-fat people’s lives at every level. The “war on obesity” has transformed fat people into medical targets for healthcare providers and non-providers alike. As I wrote previously, “When you see a fat person, you associate them with ob*sity. What you believe about ob*sity and have internalized from health authorities—its causes, symptoms, consequences, treatment, and more—then guide your interaction with that fat person. You see an affliction to be cured rather than a human being. Fatphobia starts at the top, with scientific authorities who set the tone for how we think about health and illness, then seeps down to shape the lives of every fat person everywhere.” (This pattern is a summary of what my colleague Rachel Fox and her team dubbed “pathologization”.)

Even before the issue of provider or interpersonal antifatness, receiving medical treatment on par to our thin counterparts is near impossible due to inaccessible healthcare environments and inadequate provider education and training. Even if providers didn’t hate us or could resist exhibiting their disgust in various life compromising ways, they wouldn’t be practically equipped to competently treat the fatter/est of us anyway. Engaging with providers is often unpleasant due to the rough handling of our flesh, sometimes to the point of bruising and pain. Researchers have investigated a few related issues such as lack of properly sized equipment (e.g., too-small blood pressure cuffs) but there has not been any sustained attention on the physical treatment of fat people’s bodies during clinical appointments outside of fat communities. To date, weight stigma researchers have focused on providers' negative attitudes towards fat people or how weight stigma impacts folks physiologically (with most attention towards its “ironic” impacts on eating and exercise behaviors) and... that’s basically it. The things we know about antifatness in medicine are really still community-held knowledge. This knowledge gap among providers is partly the result of weight limits on cadavers.

In one of the few formal explorations of this issue, Vice journalist Jeanne Sager found that many institutional programs through which people “donate their bodies to science” disqualify anyone with a BMI over 35. Other institutions have specific height and weight limitations or use language that indicate they use the BMI to screen out too-fat bodies; the frequently asked questions page for my own university's Anatomical Gift Program lists “extreme obesity” as a condition that may make a body “unsuitable for educational purposes”. According to Sager, some places have limits as low as 180 pounds. There is no federal standard or guideline that requires institutions to set weight limits for cadavers, but there are few institutions accepting anatomical gifts that do not reject fat bodies or near fat bodies, citing difficulties in storage and use due to their size. However, rather than creating the infrastructure to store bodies that reflect the majority of patients, fat patients are left to suffer for providers’ lack of experience. This is one of the ways antifatness blocks providers from developing the skills to appropriately serve fat patients. Not to mention the medical guidelines, insurance rules, and BMI limits on needed procedures that complicate the quality of the care we receive even from the most sympathetic practitioners. Being denied needed procedures, like gender affirming surgeries, or having care delayed until weight is lost, such as with total knee arthroplasties, are particularly detrimental to fat patients. To say all this in another way: we get sick, sicker, and die quicker because of how we are treated in medicine, the place you go when you’re sick and/or dying. Hence, all fat activists, directly or indirectly, must engage with healthcare and medical antifatness as they reckon with and challenge that contradiction.

The mainstreaming of weight loss medications into primary care—for example, by uniform insurance coverage—would worsen the lives of fat people through two main mechanisms. The first is through clinical harm. Uniform coverage of weight loss medications would essentially result in most, if not all, fat people being funneled into pharmaceutical treatment for their “obesity” regardless of whether or not they want to be. Compliance with these medications, if accepted as some kind of frontline treatment for all fat patients, could be the difference between fat patients getting care they actually need and being ignored. The withholding of needed care until future weight loss already happens, but this would exponentially worsen if there was an alternative that was “just a shot” or “just a pill” that was reported to guarantee weight loss. It’s a hostage situation worsened by the fact that you have to stay on these medications forever to maintain any weight loss in addition to our lack of knowledge about the long-term effects of these medications (hello, stomach paralysis). Mainstreaming these medications would also exacerbate the harm fat patients already experience from clinicians who blame everything on our fatness, misdiagnose us, and make weight loss the solution to all of our problems.

The second type of damage caused by the mainstreaming of weight loss medications into primary care is social harm. Our society considers health to be a responsibility or asset belonging to individuals, who are tasked with managing this commodity so that it may flourish. If individuals find themselves in poor health, that is considered a failure on their part to properly manage themselves and that failure is deserving of punishment, exclusion, or disinvestment from the collective. With uniform coverage and mainstreaming of weight loss medications, these social logics are primed to be asserted even more aggressively onto fat people.

If these medications become a pillar of primary medicine, even more fat people will be at risk of losing their lives trying to get medical treatment for everything from the mundane to the imminently life threatening. More fat people could be ostracized, isolated, violated, abused. Fighting antifatness has never been about the visibility of curvy white women with smooth skin and underarms sponsored by Dove. It is about the preservation of fat people and our lives. That goal was obscured for quite a while, but I think we’ve reached a place where, at the very least, the shallowness of that brand of body positivity can be critiqued in the mainstream. But now we are shadowed by a new moment of obfuscation. In the post-body positivity, “post-racial reckoning” era, we must learn to cut through a new cast of players who are intent on marketing weight loss as individual and public health imperatives as well as a tool to challenge our oppression.

During these past three years, the weight loss industry has furthered itself through the cause of “Black womens’ health,” and, often, through the presence of Black women themselves. Some of the most prominent representatives have been Queen Latifah, actress Yvette Nicole Brown, and other notable Black women who have participated in Novo Nordisk’s It’s Bigger Than Me campaign, which launched in 2021. It’s Bigger Than Me is, according to its website, about creating “real change” that “ends shame and shatters misconceptions” about “obesity,” encouraging viewers to see “obesity” as “a health condition, not a character flaw.” This marketing strategy—a pivot from “obesity” the “character flaw” to “obesity” the chronic, multifactorial “health condition”—paved the way for targeted clinical and policy level changes that skyrocketed the profitability of current weight loss and off-label diabetes medications such Wegovy, Ozempic (Novo Nordisk), and Mounjaro (Eli Lilly), as well as those that are rapidly coming down the pipeline, such as Tirzepatide for weight loss (Eli Lilly).

It’s Bigger Than Me involves what you might expect from a corporate advocacy marketing campaign. They have a website, social media profiles, hashtags, and paid spokespeople, including celebrities, academics, healthcare providers, and influencers. It’s Bigger Than Me Live is a “three-city tour designed to encourage and empower honest conversations” about obesity, with Queen Latifah acting as host beside a “panel of experts.” It’s Bigger Than Me Series consists of four episodes featuring Yvette Nicole Brown, who hosts conversations with other spokespeople to “unpack the reality of living with this disease.” The hosts interact with spokespeople who are Black and not, fat and not, but that’s also not really the point.

Latifah and Brown’s positions as Black women with lifelong associations with fatness (although they are both in notably smaller bodies than in the past) are essential to the roles they play as intermediaries between other spokespeople—especially white thin spokespeople who have long-term affiliations with the weight loss industry. The campaign uses Latifah and Brown to lend legitimacy in the eyes of a Black and/or fat public audience to industry players and Novo Nordisk spokespeople like Joe Nadglowski and Dr. Scott Kahan. Nadglowski acts as President/CEO of the Obesity Action Coalition, an advocacy arm and fundee of the weight loss industry. Kahan serves as Medical Director for the STOP Obesity Alliance, “a diverse group of business, consumer government, advocacy, and health organizations dedicated to reversing the obesity epidemic in the United States.” Novo Nordisk is a top financial contributor for both the Obesity Action Coalition and STOP Obesity Alliance.

The weight loss industry has also been collaborating with longtime advocates for “Black women’s health,” lending their strategy a different kind of legitimacy. In 2020, Novo Nordisk funded “A Courageous Conversation about Obesity, Healthy Lifestyles, and Black Women”, a program that emphasized how Black women’s “obesity” rates and lack of access to “obesity medicine” are based in racism and sexism. It was put on by the Black Women’s Health Imperative (BWHI)—a group with roots in radical reproductive rights advocacy—in collaboration with the Obesity Action Coalition. BWHI also worked with industry stakeholders on the Novo Nordisk-funded 2021 campaign Reclaim Your Wellness, which focused on “making obesity a healthcare priority, while improving the lives of people with obesity; changing how the world sees, prevents and treats obesity as a disease; and ensuring people living with obesity have access to science-based, comprehensive care.” The first webinar featured comedian and former co-host of The Real Loni Love (who has shared she was inspired by Oprah to become a Weight Watchers brand ambassador).

If you’re wondering how BWHI, with its roots in “radical reproductive rights advocacy,” ends up being involved in something that is ostensibly harmful to fat Black people, it’s because most advocacy groups that focus on Black women’s health, or “minority health” in general, tend to build their priorities around health disparities, or the concept that there are health outcome differences between groups due to those groups’ disparate access to social, political, and material resources. For these groups, their goal is to eliminate health disparities in areas such as birth-related mortality or “obesity” by focusing on the “challenges” that explain Black people’s disproportionate risk for them. While these challenges are symptoms of living in a world oriented by antiblackness, their interventions in these spaces are usually centered around the Black individual’s capacity or desire to make “good choices” in death-dealing environments, as well as shallow notions of the power of representation. Antifatness runs rampant in Black women’s health or “minority health” advocacy, as Black “obesity” is often seen as an injustice wrought by “food deserts,” “unhealthy” cultural behaviors, and sedentary environments. Ultimately, the matter of how “radical” these groups are in their approach to “Black health” is wholly dependent on a host of factors, including funding, as well as their investment in paternalistic forms of health promotion.

BWHI also collaborated with several weight loss industry players (including a Novo Nordisk Senior Medical Director and Obesity Action Coalition board members) on a National Consumers League 2022 report titled “A New Patient Centered Obesity Action Agenda.” The report advocates for changes that further the weight loss industry’s promotion of weight loss medications, including more “obesity” education for training and practicing doctors, establishing “excess weight” as a vital sign akin to body temperature and heart rate, covering “obesity” treatment across the insurance industry, removing Medicare rules that exclude weight loss medications from Medicare Part D coverage, and more.

One of the professionals who participated in the 2020 “Courageous Conversation” program was Dr. Fatima Cody Stanford, an “obesity medicine” physician-scientist affiliated with Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School. She has also emerged as a key player in the weight loss industry’s promotion of weight loss medications over the past few years. By her own estimation, she does up to 200 news media interviews and an average of 150 lectures per year about “obesity as a disease.” In 2022, Dr. Stanford co-authored a STAT News op-ed with Eli Lilly’s Global Head of Diversity Equity and Inclusion, Kelly Copes Anderson, in support of the Treat and Reduce Obesity Act, which stands to be highly profitable for current and soon-to-be producers of weight loss medications. Two proposed elements of the Act, which was first introduced in 2013, involve broadening Medicare coverage for intensive behavioral therapy to reimburse more providers, as well as covering FDA-approved weight loss medications under Medicare Part D. Their op-ed notes that “nearly 50% of Black adults and 45% of Hispanic adults have obesity,” before arguing that “the significance of these two [proposed elements] goes beyond treating individuals with obesity. They represent a decisive moment in shifting society away from viewing obesity as caused by individuals making poor choices and toward treating obesity as a manageable chronic disease like asthma or high blood pressure. This is a crucial step in eliminating bias against people with obesity, which has hobbled efforts to address this epidemic even as it fuels health inequity.”

In January 2023, Stanford was one of two experts, both of which were paid Novo Nordisk consultants, featured in the 60 Minutes segment “Recognizing and treating obesity as a disease.” Stanford used the rhetorical slant she often uses, the same discourse that is present in most of the industry’s present marketing, such as It’s Bigger Than Me. She takes the “empathetic debunker” position, highlighting the inaccuracies of how we, including other doctors, understand causes of “obesity.” She argues that “the number one cause of obesity is genetics,” as well as using sympathetic language to describe her fat patients (“My last patient that I saw today was a young woman who’s thirty-nine who struggles with severe obesity… She’s eating very little. Her brain is defending a certain set point.”) In the structure of Stanford’s discussion of “obesity,” having access to weight loss medications is a solution to bodies that are physiologically wired to protest against weight loss as well as a way to address anti-fat stigma that her patients deal with in their lives.

She may have laid it on a bit too thick considering that the FDA confirmed its plans to investigate the 60 Minutes segment after a nonprofit physicians group filed a complaint about it being an ad for Novo Nordisk medications. In the complaint, the group also cited over two hundred thousand dollars in contributions from Novo Nordisk’s PAC to federal candidates in 2021-2022 as part of them “actively funding an effort to pass federal legislation such that the U.S. government would pay for Wegovy for the treatment of obesity as part of the Medicare and Medicaid benefit.” Still, there are good reasons for why it is difficult to read or watch current media discussing “obesity stigma” without coming across Stanford.

Stanford—a thin Black female “obesity medicine” practitioner—plays a different role within the weight loss industry’s strategy to maximize its profits than Nisha Godfrey, Queen Latifah, or Yvette Nicole Brown; her positioning outside of fatness is crucial to the legitimacy of her expert status granted by her degrees and professional status. And her own Blackness is essential to her ability to say she has special insight into what causes fat people, especially Black fat people, to become and stay “obese.” This holds even if she, herself, is not fat. Black people, specifically as a “population of focus” for health professionals and researchers, are never not struggling with our unruly bodies, never existing outside the context of poverty, “food insecurity,” “lack of access” to one thing or the other, and so on. We are abject aliens to white people, who are always grappling with how to ‘reach’ or ‘understand’ us (for extractive purposes). Stanford, as a thin Black physician, can play the dual role of knowledgeable insider while also being legitimized by her professional, class, and body status. Still, despite wielding this special dual role, she performs in the same exact context that Godfrey, Latifah, and Brown all do.

To appreciate the significance of the weight loss industry’s engagement of Black women and “Black women’s health,” we have to talk about what I am calling health equity capture, a form of elite capture pertaining to the appropriation of health equity concepts, aesthetics, and language.

In a 2022 article by Dr. Elle Lett and her co-authors, they coined and described the term health equity tourism as follows: “The practice of investigators—without prior experience or commitment to health equity research—parachuting into the field in response to timely and often temporary increases in public interest and resources.” Health equity tourists flock to health equity work because they see potential for research productivity or fiscal return due to market favorability.. The commentary cites the influx of researchers focusing on the disproportionate burden of COVID-19 experienced by Black and Latinx people in the US––several promoting genetic causes as an explainer for these disparities––diluting the field and drowning out the voices of experienced members of the health equity research landscape.

While health equity research has historically been a field of lesser focus primarily made up of non-white people who belong to the communities they focus on, Lett and her co-authors note that the capitalist structures that determine researchers’ success ultimately incentivize bandwagoning onto trendy topics––like health equity––by people with no true connection to them. Health equity tourism thus falls under a broader umbrella of health equity capture. Health equity capture iselite capture pertaining to the appropriation, or “hijacking” of health equity concepts, aesthetics, and language. It hijacks health equity concepts, aesthetics, and language by the “well positioned and better resourced” for the purpose of posing the problem—in our case, the institutions and processes (like the weight loss industry) that create, prop up, or exist due to inequality—as the solution. Elite capture comes from global development studies and has typically referred to how elite groups gain control over what is meant for all, such as via corruption or bribery. However, as Olúfémi O. Táíwò writes in his book Elite Capture (2022), it can also describe how political projects, like activist work, “can be hijacked—in principle or in effect—by the well positioned and better resourced.”

There is nothing in an unequal society that is safe from elite capture. As Táíwò notes, it is not about an individual’s or institution’s conscious will to do elite capture that results in elite capture—although singular examples, like certain marketing choices, are as intentional as they seem. Elite capture is the logical result of systems, processes, and histories in which inequality is inscribed. Ideologies, knowledge, frameworks—they are all resources that can be and are unevenly distributed, hoarded, withheld, and co-opted for hegemonic ends.

An essential component of the industry pivot from “obesity,” the “character flaw” to “obesity” the chronic, multifactorial “health condition” is the acknowledgement that “obesity” is impacted by social determinants of health like poverty and racism. The acknowledgement of how something like racism can create physiological or social conditions that result in “obesity,” when paired with the evidence that Black women are the (overly simplistic) racial/gender group with the highest proportion of “obese” individuals, makes room for the weight loss industry and its proponents to say that making weight loss drugs available to fat Black women is a health equity issue. And that is precisely what they are doing. By hijacking concepts like equity, justice, and stigma; buttressing themselves with fat and not-fat Black women ambassadors; and manipulating rhetoric to equate weight loss with ending weight stigma, the industry is opening itself to levels of revenue it has never seen before—and even seeming more empathetic to fat people while doing it.