Memorial altars in Los Angeles offer resistance to the digital

Anyone can be a curator online, arranging image-objects and images of objects as they please, even if they may never see these objects in person. In its relationship to digital imagery, the trend in curation subtly undermines awareness of the structures that deny true access both to material goods and space.

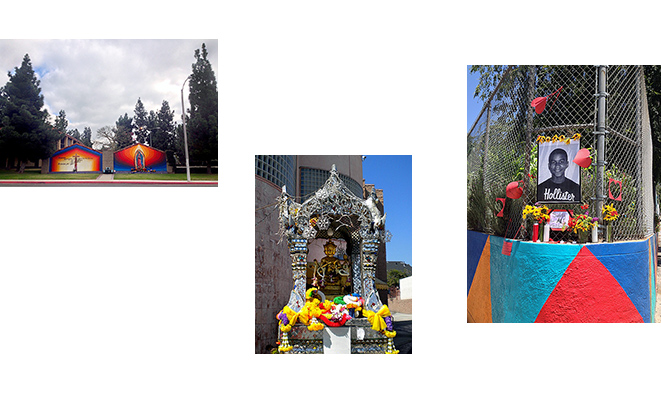

Altars resist this erasure. As installations, they are inherently site-specific. Sometimes, as with memorial altars, the reasoning behind the site is obvious, and other times it may seem more arbitrary. They very often incorporate photographic images, but they just as frequently rely on photography’s predecessor, the icon. They are adaptable and porous, fitting simultaneously with histories of folk religion and paganism as with narratives of postmodern hybridity. They are almost always recognizable in their form, but no two are alike. Each unit is an individual expression of its maker’s intention to remember something that cannot be seen, because it exists first and foremost in their own mind. In this way, the altarmaker employs visuality as a manifestation not only of their faith in what’s being represented, but in the personalized act of representation.

The tempting slippage between altar and alterity has been expanded upon by at least one scholar. As a condensed, physical unit of curation, the altar can be seen as a passive disruption in the mechanisms of capitalist visuality, one that paradoxically expresses faith in the unseen while worshipping visibility itself.