On Richard Hell's I Dreamed I Was A Very Clean Tramp and the art form of persona-creation

My introduction to the 1970s New York punk scene took place in the bathroom at the Hungarian Pastry Shop. On a wall by the mirror, amidst all the other pretentious graffiti there, small, neat capital letters spelled out the words “Punk is making up life for yourself.”The quotation was attributed to Legs McNeil, in Please Kill Me. I had no idea who or what that was, but I was nineteen years old, and the idea of self-reinvention was my catnip. I bought a copy of Please Kill Me, Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain’s account of the 1970s punk scenes, that afternoon. Actually listening to the music came next, as a sort of footnote. I got to the punk scene through its philosophies, the big worded and wild-eyed myth-making of its participants. Punk was making up life for yourself, punk was inventing yourself, and punk was inventing the people around you, too, inflating them to the size of Gods or perhaps just cartoons. Punk was a scene and scenes are a form of myth-making.

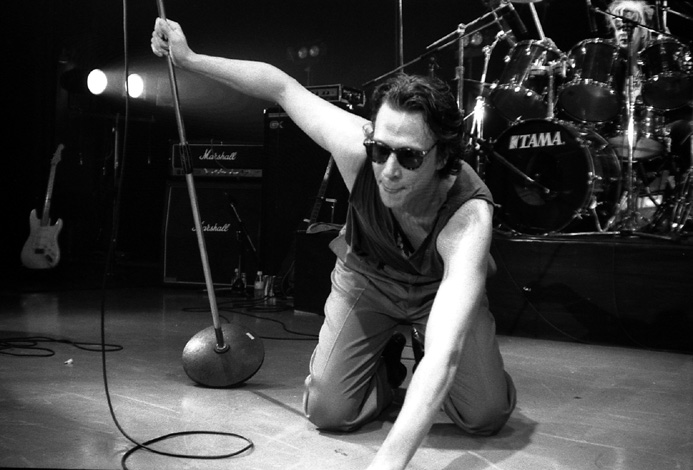

In the past few years, the elder statesmen of this particular New York scene -- patrons and stars of CBGBs between the late Sixties and mid-Eighties, to vastly oversimplify a category -- have come out with their own literature, and enough has been written by and about them to make the telling of this particular scene almost a genre unto itself. This year, Richard Hell, punk rock pioneer with bands such as Television, The Heartbreakers and The Voidoids, published his memoir I Dreamed I was A Very Clean Tramp. The memoir comes less than three years after Patti Smith’s Just Kids, a memoir of the exact same scene, if from a very different perspective.

Much of the fun of Hell's book is its plurality and intertextuality, the way in which it interacts with previously and recently published works. The scene in which Hell describes Patti Smith’s first, momentous performance at St. Mark’s church calls up the central scene in Just Kids where Smith describes her own memory of this same evening. While there’s no real discrepancy-- everyone could tell Smith was a transcendentally compelling, illogically hyper-sexual genius of a performer -- what’s fascinating is the way in which these multiple voices begin to create a collage of New York in the 70s.

Hell’s narrative follows the same trajectories of the same group of people, their journey from disparate, lonely kids to a group of people known for creating a certain type of art and music. There is, once again, the story of Television talking CBGB’s owner Hilly into giving them a Sunday night gig, of which I’d read at least five other printed versions, none of the details of which quite square each other. The same established figures feature as inspirations, and the same unexpected nobodies emerge from shadowy corners at Max’s to become somebodies. The book runs parallel to existing downtown histories, adding itself as one more voice in a familiar narrative.

Hell’s memoir begins with his determined, adolescent arrival in New York. The coming to New York narrative is its own form of punk: punk is making up life for yourself, and New York is where people go to make up new lives, to invent themselves over again. Hell tells us, in easy, informal, and occasionally stilted prose, the story of how he did just that. As it so happens, that’s also the story of how he made up punk for everybody else. We watch him seize the world with the audacity of his own fiction, determined to to catapult himself into the merciful possibility of artifice.

Hell arrives in New York with the intention of becoming a poet. As was the case for so many people in this same scene (and in another parallel to Just Kids) he fails at this particular endeavor and, in failing, becomes a rock star instead. The book chronicles his relationship with Tom Verlaine, the other frontman of the band Television. It details the success of Television and then Hell’s ultimate break from the group due to his personal (as well as artistic) rift with Verlaine. It takes the reader through his subsequent work with The Heartbreakers and then his formation of The Voidoids, with whom he finally released and had a platform for the punk anthem “Blank Generation.” It tells the story of his confrontations with British punk on the Voidoids’ European tours, and follows his drug addiction, his numerous relationships with numerous, numerous women, and his interaction with just about anyone you’ve ever heard of from 1970s downtown New York City. In narrating the events of his own life, Hell tells the story of the rise, saturation, and ultimate deflation of CBGBs and the scene that grew out of it.

Television is the band that originally brought Hell to prominence, but the details of his split from the band are vague, and “Marquee Moon, their definitive album, is barely mentioned. Despite the years that have elapsed, Hell seems too close to the material to talk about it. The wounds are just too raw. Just as Patti Smith's relationship with Robert Mapplethorpe is what made Just Kids so moving, Hell’s relationship with Tom Verlaine gives I Dreamed I Was A Very Clean Tramp its emotional anchor, only Patti Smith had lived long enough away from these events that they no longer felt current. There’s no such closure or distancing to Hell’s prose, and the result is exhilarating in exactly the same way his music and the music it spawned is exhilarating. Hell is still angry at Verlaine, still doesn’t want to talk about Marquee Moon, still anxious to proclaim his own genius and still possessive of the importance of “Blank Generation.” He’s angry about slights that took place forty years ago. He still wants to fuck the girls he was fucking when he was 19, and still is racked with injustice over girls he didn’t get to fuck. He’s still jealous of the Sex Pistols, and he still misses heroin. It’s childish, bratty, and fantastic.

Hell’s account of his relationship with Verlaine effectively ends less than halfway through the narrative. Yet that relationship remains the central story of his memoir. Too often, stories about youth told by people who are not young focus, incorrectly, on romantic love. But traditional, romantic love is not what defines our formative years. As we emerge into, out of, and back and forth from adolescence, what defines these years of self-formation are the friendships. Hell and Verlaine, in their early years together, after they escape from the same boarding school and then meet up again in New York, are not simply constant companions. They define and mold each other’s emergent personas.

Hell talks about this blending of self, the way in which the two became inextricable creations of one another: “Our mentalities got intermixed....People thought we were brothers... Our speech tones and patterns even became similar-- people mistook us for each other on the phone. [...] It was the most meaningful friendship I’ve had, I think, and the last male friendship of its importance.”

People would mistake Hell and Verlaine for brothers, Hell recounts. The mistake is exciting because they aren’t. Their sameness is trained, chosen, rather than ordained from birth. This kind of love is a rebellion, a freedom from the strictures of home and family. Punk is friendship, not love. It is the friend with whom we are literally or figuratively cutting class and hiding behind the gym, smoking and making plans to run away. In counter-cultures that refuse and reject patterns of domesticity, tradition, and adulthood, we define ourselves far more by strange friendships, by relationships that mimic not the love our parents were (or were supposed to be) in, but the camaraderie we had with our childhood best friends. These are the people with whom we first discovered connections outside of the familial, ties outside of those dictated by blood and DNA.

Hell describes staying up all night talking with Verlaine in the early days of their friendship. “There’s an eternal, godlike feeling to sitting with a good friend in the middle of the night, speaking low and laughing, lazily ricocheting around in each other’s minds,” he writes, then calls those nights, those endless conversations “the strongest dose yet of my favorite feeling: of leaving myself behind for another world.” He goes on to compare this feeling to the one he got from sex or drugs, but more so. The friendship with Verlaine is the strongest thing in an arsenal of rebellious behaviors by which Hell is defining himself and mapping out his own world.

If punk is making up life for yourself, Verlaine and Hell make up life for each other, and make up the other for themselves. Relationships like these are always about self-definition. They teeter on the border between family love and romantic love, and come to define a time when everything is liminal, when everything is a negotiation of borders and boundary-spaces. Throughout the early parts of the book, Hell narrates influences to which he introduced Verlaine and vice versa, everything from poetry and philosophy to drugs and getting gigs for the band. They create a language out of what they share with each other. Both their stage names, which each kept all his life, are collaborations. Hell describes searching for the perfect reference to a French poet, why nothing worked except “Verlaine,” and how “Hell” with its reference to A Season in Hell linked them by making them into a new version of Verlaine and Rimbaud. They create themselves through this other person, through mimicry, imitation, and agreed-upon invented languages.

In talking about Verlaine, Hell’s narrative voice turns from that of a cool and wise poet to that of a wronged child. He complains about things he discovered for which Verlaine was credited, things Verlaine learned or outright stole from him, all in the jealous, immediate language of a break-up in the present tense. “We hated each other,” explains Hell, “as only best friends can.” After Hell’s departure from Television, Verlaine is barely mentioned, but it's clear that Hell remains attached to Verlaine and to the idea of punk itself, despite his having left both the man and the scene decades ago.

Punk may be about making up life for oneself, but its central figures made up that life out of reference, not out of thin air. It is more an assemblage than a creation. Two of Patti Smith’s greatest songs -- “Hey Joe” and “Gloria” -- are viciously re-imagined covers of pre-existing material, after all. Similarly, I Dreamed I Was A Very Clean Tramp is filled with homages and literary references. Hell and Verlaine try heroin “because we were interested in William Burroughs and Lou Reed.” Hell’s series of small, lonely apartments are made bearable by thinking of poets such as Rimbaud who lived in small, lonely apartments. His girlfriends look like Bob Dylan’s former girlfriends, his nights of black-out drinking recreate Dylan Thomas’s nights of blackout drinking. Even Hell and Verlaine’s invented names are references to poetry. In earliest chapters of the book, Hell details how he was punk before he knew what punk was, his childhood signposted by experiments with drugs and stealing cars, usually both at the same time. These examples of the death drive - examples that would come to define punk music -- don’t even emerge from a continuum of rock music. Rather, Hell tells us how he based his “no future” choices on the philosophies of French poets such as Baudelaire. Hell also name-checks Frank O’Hara frequently, linking the amateurism and studied spontaneity of “Lunch Poems” to the ethos of punk.

Hell's book ends with an encounter with Verlaine in an East Village bookstore. The myth-making, it appears, has worked. They pick up bantering about nothing as though no time has passed and no break has occurred. “When Tom spoke to me there outside the bookstore,” Hell explains, “it was forty-two years ago, 1969, and he was nineteen years old; we both were. His misshapen, larded, worn flesh somehow just emphasized the purity of the spirit inside. He made a bunch of beautiful recordings too. Who gives a fuck about the worldly achievers, the succeeders at conventional ambitions?”

But of course, Hell succeeded at exactly the ambitions he set out for himself at nineteen; Verlaine too. While both of them may be “misshapen, larded, worn” and neither may be conventionally famous or wealthy, they’ll be written and spoken about, cited as influences by kids starting bands and moving to the city, for generations after they’re gone. Someone has asked them to tell their story, and cared enough to bring it out in hardcover, and here I am considering it as part of a larger literature about this particular scene.

In the epilogue, Hell describes himself and Verlaine as “two monsters confiding.” Much earlier in the book he defines rock stars as a kind of monster. To reinvent oneself, perhaps one always has to become a monster, larger than life and at least a bit ruthless. But the fiction of himself, and of the scene around himself, in I Dreamed I Was A Very Clean Tramp, goes one step further and makes an argument for persona-creation as a useful art form. Hell offers his invented self to a next generation of longing kids. These are the kids reading this and Smith’s memoir and all the other books about New York in the 1970s, and making up life for themselves, locating the quotations out of which the next generation of punks will invent themselves.