The Union of Radical Workers and Writers (URWW) Mission Statement, March 24, 2005:

The URWW network strives to confront, impede, and revise neoliberal policies and practices in the everyday lives of workers of the word. Understanding the larger and ultimate political project of these neoliberal policies and practices to be the abolition of collective action “for humanity and against neoliberalism,” we seek to establish public platforms and virtual networks for the democratic struggle to work in the first-person plural.

•

ZAINA ALSOUS. Can you share a bit of the history of the formation of the URWW, how it came about, and what a vision for working in the “first-person plural” means to you/all?

MARK NOWAK. Jason and Holly and I were already meeting up for a while after Borders workers announced their organizing drive at the Borders bookstore in Minneapolis. I had gone to South Korea for a few weeks in the summer of 2002, I believe it was, where I gave a talk to the English teachers’ union and traveled around the country visiting the Hyundai factory and other sites. At this time, I was reading a lot on small Marxist organizations that C. L. R. James had formed (and regularly separated from): the Johnson-Forest Tendency, News and Letters Committees, and especially Facing Reality. It felt, to me, like a usable model for forming a group that would aid the organizers of the union drive and, potentially, radicalize the larger community around issues like this. The Twin Cities with all its renowned presses and bookstores and literary institutions felt like it had the potential to become a kind of center for this type of activity given the nature of this struggle. Ultimately, this didn’t prove to be the case.

JASON EVANS. For us, it was connecting the material site of Borders to larger ideas and ideologies of organizing. The URWW was significant because it would broaden our politics. I didn’t have too many connections in the radical political movements here before the Borders drive. It was through the URWW that I met others—it was my conduit to becoming more politically conscious. Reaching out to other stores was almost impossible beforehand. The URWW helped make this happen and this was hugely important.

What was the impetus for organizing the Resist Retail Nihilism conference? What conversations and connections happened there, and what collective objectives came out of it?

HOLLY KRIG. I think what became most clear for me and others was that organizing a workplace—as we did successfully at the Uptown Borders—is far more impactful if we approach that as a community-building effort as much as a campaign against exploitation. It was so crucial to see beyond the specifics of our particular jobs and jobsites in order to see comrades sharing struggle, both the economic and the despair of endless, isolated struggle. It was crucial to acknowledge that we were each so much more than our wage labor; our individual identities should not be used to further exploit us by employers seeking to divide us; rather, we are best supported in a community of workers. It was also important to consider, through that shared space of the conference and the relationships that grew from it, that there is no “somewhere else,” as the employer loves to say to workers demanding more. The same conditions underlie all wage labor, the violent history and systems that sustain it, and we have to meet there at that realization, and arm ourselves, first and foremost, with imagining a new world, a somewhere else in the making.

JASON EVANS. For me, there were more practical connections. I met Emmanuel Ortiz from the unionized Resource Center of the Americas bookstore [and] got in touch with people from Powells, the Borders people in New York. It gave me a wealth of information on Borders strategies. These new connections sent me materials: minutes from meetings on the contracts, their tactics, etc. It felt like we were inventing this retail-organizing model, especially from the Powells people. It reduced that isolation as a worker. It was also bringing the radical writers in, like you, Mark, and Sun Yung Shin and Emmanuel. This was the kind of language I otherwise had only heard in punk and hip-hop. That felt like something we could really develop.

What were some of the key lessons you learned in attempting to organize with writers and retail workers? Did it change your relationship to poetry?

MARK NOWAK. [A key lesson was] that most writers aren’t interested in class struggle, to be blunt. I was really rather astonished that, aside from poets Sun Yung Shin and Emmanuel Ortiz, who was working at the time at another great unionized store, the bookstore inside the sadly defunct Resource Center of the Americas, no one was really interested in joining us in our regular URWW meetings and in our public actions at the store and at our national conference of bookstore workers. I remember a protest we publicized pretty widely that was going to take place out in front of the store on the day after Thanksgiving (I was also head of the Political Action Committee of the Twin Cities branch of the National Writers Union at the time, and I’d been editing XCP: Cross Cultural Poetics for about six or seven years in Minneapolis by this point, so I had a pretty decent Rolodex of contacts in the writing community); well, I was pretty surprised that not a single writer showed up that day. There were labor activists and others, but not a single author.

Typically, socialist organizing grapples with the question of how to advance the material conditions of the working class. Do you think that advancement can be made through and within writing?

HOLLY KRIG. I believe that this is absolutely true, though I no longer remember how clearly I understood that at the time we organized our bookstore, and formed URWW. I think it took some time to realize that my own experience of struggle and poverty in an isolated, rural community, and my fear that I would always struggle to survive in vulnerable, even unsafe circumstances—which low-wage work would never keep me safe from—was underlying my desire to build toward a liberatory politic. It is through writing and reading personal narratives that I more fully understand how low-wage work—and lack of affordable housing, health care, clean water, etc.—supports other (poverty is violence too) kinds of violence women experience in their homes and communities, especially women of color, undocumented, and trans women. It was through writing and reading the words of women who shared an experience of violence that I began to think about liberation in terms of mutual-support organizing, supporting survival as we move beyond a world where basic needs are met through transaction, and people who are forced outside the formal labor market to meet those needs are criminalized. I think the only way we can take on the despair we carry from personal histories and very contemporary exploitation is through writing our way right to the center, meeting there together, and organizing like our lives depend on it—and they do—toward the new futures we write, together.

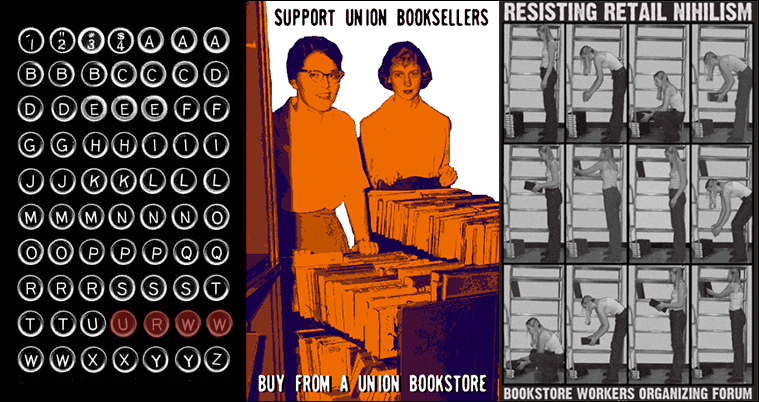

JASON EVANS. I also think we did amazing work with our posters, our flyers, our website. For me, the aesthetic elements are important. The dated “older white man” aesthetic of wrenches, hard pails, and hard hats doesn’t translate to retail work and young workers. We tried to bring relevant, contemporary language to political organizing. Although we’re seeing some of this today from worker centers, we don’t really see it from the unions with money. We looked at the AFL-CIO websites and we said, “Gross!” As a worker in your twenties, you looked at these websites and you said, “This isn’t me.” And if you joined one of those unions, this old aesthetic was really what you got. Breaking the cliché was an attempt to reimagine what could happen in these unions. Seattle—the WTO protests in 1999—was really important to us. That merging of trade unions and social movements. It was pretty exciting. And the Zapatistas. The odds against the Zapatistas were gargantuan. Their communiqués and other materials were interesting, well packaged, accessible. It felt like a small organization could do the impossible, that broad, international organizing from the jungles of southern Mexico could have such reach. It gave us hope. The Zapatistas “packaged” themselves, for lack of better words, presented the movement in such a way that you’re going to garner tremendous support. I think that’s something the Left overlooks. Plus, it captures the imagination, it’s more motivating. I think we developed a new modern language and aesthetic for the trade union movement, or at least that’s what we were trying to do.

Most of the creative writing workshops I’ve been a part of emphasize the role of the poet to excavate their individual experience as a political gesture. How can poets and writers see themselves and the work of poetry as embedded and accountable to a broader working class?

MARK NOWAK. Maybe the models the creative writing workshop teachers are using are a bit dismissive of the working class and the history of workers’ culture? When you look at important writers from across history and around the world—writers like Meridel Le Sueur, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Muriel Rukeyser, and so many others—there’s certainly a strong sense of writers “embedded and accountable to a broader working class.” One of the things we’re trying to do at the Worker Writers School is to bring the incredible range of global political literature to the workshop environment and use those works as inspiration and models for participants who come from these fabulous worker centers in New York City: Domestic Workers United, the New York Taxi Workers Alliance, the Street Vendor Project, Retail Action Project, the New York Worker Center Federation, and others. We look at poets from across the spectrum, many of whom have been largely either excised from the canon or never managed to be considered for it in the first place, poets who maybe haven’t won prestigious awards or been in the anthologies usually taught in university classrooms but who nevertheless we feel are vital poets of today. I’m thinking here of some recent poets we’ve used in workshops: Etheridge Knight, the new anthology of Chinese worker-poets [Iron Moon, from White Pine Press], the extraordinary Cuban poet Nancy Morejón and her collaborative book with documentary photographer Milton Rogovin, writings from anthologies like Thunder from the Mountains: Poems and Songs from the Mau Mau, or the great South African anti-apartheid worker-poetry anthology Black Mamba Rising. Really, there’s so much out there.

In the essay “Poet’s Strike (version 2.0),” Mark writes that a onetime strike event probably isn’t enough for poets and writers to enact significant resistance. A lot is being written about the role of “political poetry” in the midst of neofascism. How can we stop thinking about poetry as detached exalted narration? How do poets actually shut shit down?

MARK NOWAK. I’m not sure I’d separate poets or writers from everyone else. If we really want to “actually shut shit down,” that’s a massive project. We need poets and writers, sure, but we need workers and students and everyone. Every time I’m reading Ngugi’s work, I underline when he talks about the unity “with workers and peasants,” and I have a lot of underlines in so many of his books, books like Detained: A Writer’s Prison Diary and Barrel of a Pen: Resistance to Repression in Neo-Colonial Kenya. I’m actually not so much a fan of “political poetry” as I am of political movements, of building them. Then again, there’s the example of our collaborators at the New York Taxi Alliance who actually did “shut shit down” during their one-hour protest that silenced the international terminal at JFK airport after Trump’s #MuslimBan. Christine, who has been with our NYC workshops from the very beginning with Domestic Workers United, always makes us happy when, at the end of our Worker Writers School workshop, she reminds us that this, too, is a movement. We, as worker-writers, are building a movement.

CHRISTINE LEWIS. It is a movement, Mark! How long have we been on the front line speaking our truth to power? The writing workshop which began in New York City with Domestic Workers United, and then other groups, as Mark mentioned, were added on along the way. Listen, some movements haven’t made it past two years, and we’re in our seventh. It has to be a movement. Can you imagine sitting with other groups whose struggle is the same as yours? We’re still within our community fighting for a decent living wage. More so in this era of #45. How important is community? We’ve got the sword which is the word and each other when we sit to scribe our struggles. Hello!!!!!!!!!! We are griots, we are sadhus and sages, we are preachers, teachers, wordsmiths, prophets. We are poets. Let me tell ya, vexation of spirit and sick and tired of being sick and tired build movements. Especially when you are working on the margin or just simply excluded from most labor laws. Or, where you might have emigrated from. Here at the Worker Writers workshop we come bearing love and vexation of spirit. Then our pen becomes our friend, and we get to write what Mark prompts us to write or not write. But to look in our heads and write. We write our truth. We are a movement. Fearless.

What do you think a mass organization of worker-writers and writer-workers could look like?

CHRISTINE LEWIS. A force to be reckoned with. No borders. No walls. We must tell the truth. As Jewish Puerto Rican writer Aurora Levins Morales said, “Our stories are our medicine.” Writers are healers. Writers are magicians. And if we come together in a cohesive way, we would write anything we want into being. Remember what I said before, we are griots and sages. We’d write 45 and his cohorts right out of dat oval office. We’d truly shut shit down. We have the power in our hands. The pen. Note, I didn’t say a gun.

MARK NOWAK. And this is one of the things we’re talking about now. The Worker Writers School this fall expanded to Buffalo and Albany, New York’s capital. And we’re in conversations with people in Chicago, in Oakland, and in Miami about offering Worker Writers School programs there, too. We’ve built the NYC hub over seven years, so we’ll see what the next seven years will hold for, as Christine says, our movement.

•

Jason Evans, co-organizer of the Borders Uptown union drive in Minneapolis, is currently a graduate student in mathematics, a math tutor in the Twin Cities, and a member on AFSCME.

Holly Krig, co-organizer of the Borders Uptown union drive in Minneapolis, is the director of organizing for Moms United Against Violence and Incarceration, coordinator of Reunification Ride, and mom of a 5-year-old named Sophie Lucy Parsons.

Christine Lewis is a musician, poet, and activist and the Secretary and Cultural Outreach Coordinator of Domestic Workers United.

Mark Nowak is author of Shut Up Shut Down and Coal Mountain Elementary and founding director of the Worker Writers School.