The following excerpt is from Anastasiya Osipova's Black Squares, the introductory essay to Cicada Press's beautifully designed newsprint publication of essays on Maidan, art and their interpolation titled Circling the Square. It is available as a PDF immediately (for a pay-what-you-will donation) at Cicada Press' website, and will be released as a full-color newsprint next week. For those in the New York City area, a launch event, featuring co-editors Osipova and Matthew Whitley, Olga Kopenkina, who curated artworks at Maidan, and Ian Dreiblatt, one of Circling the Square's translators, will be held at the Interference Archive next Tuesday, June 26th, at 7PM.

Art Arsenal museum, founded by the dashing Natalia Zabolotnaya, the platinum-blonde wife of a deputy, positions itself as a main venue and vehicle for popularizing and supporting modern and contemporary art in Ukraine. To walk in step with the governmental line, the administration of this institution decided on the occasion of the anniversary of the Baptism [of Kievan Rus], to somehow reconcile its ‘progressive’ orientation with the official endorsement of clericalism by gathering everyone and everything under the banner of “spirituality” in art. Only a very supple and generous imagination could stretch far enough to make this connection between most of the very eclectic objects culled for the exhibition and the spirit of Christianity. The very first item that a visitor to Arsenal saw after the ticket booth, was a proudly displayed and lit Peugeot car of the latest model (its presence being as straightforward as it was inexplicable from the point of view of either art or “Christian values” - no performance artist was crucified on its hood). A few halls down, mammoth bones with ancient pagan carvings were displayed next to Constructivist sculptures – for their formal purity, I suppose.

To cite the press release:

“Great and Grand seeks to examine the civilizing effect of Christendom on the development of Ukrainian culture, and to demonstrate how the modern individual – embracing the history reflected in this sublime artistic legacy – involves himself in it, and invigorates the sense of what it is to be Ukrainian.”

It is not hard to guess that only a miracle could have prevented the internal contradictions of Arsenal’s politics from detonating, and sure enough, the explosion did go off.

On the eve of the opening, Zabolotnaya was making her final rounds examining the process of the installation. Passing by the “Last Judgment” mural by Volodymyr Kuznetsov, still in progress at that time, she found his vision of Apocalypse so genuinely disturbing, that she hastened to personally paint it over with black paint. (It should be noted that she had commissioned the mural, and that it was both aesthetically and thematically consistent with Kuznetsov’s previous work of the same Koliyivshyna cycle, named after the eighteenth-century Ukrainian peasant and Cossack rebellion against Polish oppression.)

What frightened Zabolotnaya so?

Only a few low-quality cellphone photos of Kuznetsov’s mural survive. As commissioned, he painted a scene of the second coming of Christ, who arrives to earth to right all wrongs. Aided by Chernobyl firemen, angry pensioners, Pussy Riot members, workers, and Irina Krashkova from Vradiivka village (whose unpunished rape and attempted murder by five policemen prompted a large popular protest earlier that summer), Jesus ushers corrupt politicians and judges, together with clergy, mafioso, their whores, and luminous limos (the likes of which not only stop general traffic for hours, but also, have struck dead many pedestrians on the streets of Ukraine, with their drivers unthreatened by prosecution) straight into the fiery pit of hell.

When asked to comment on her actions, Zabolotnaya’s initial response was a model of populist fury: “the artist has offended his motherland, and it is an unforgivable crime, like offending one’s mother.” In a few days, however, she came to her senses, and offered a more ‘sophisticated’ explanation, claiming (as per Boris Groys’ theory) that the curator is the new artist, and this act of vandalism was nothing less than her own personal performance.

Another artwork was removed with less sensational coverage from the exhibition - a painting by Vasiliy Tsagolov titled “A Molotov Cocktail.”

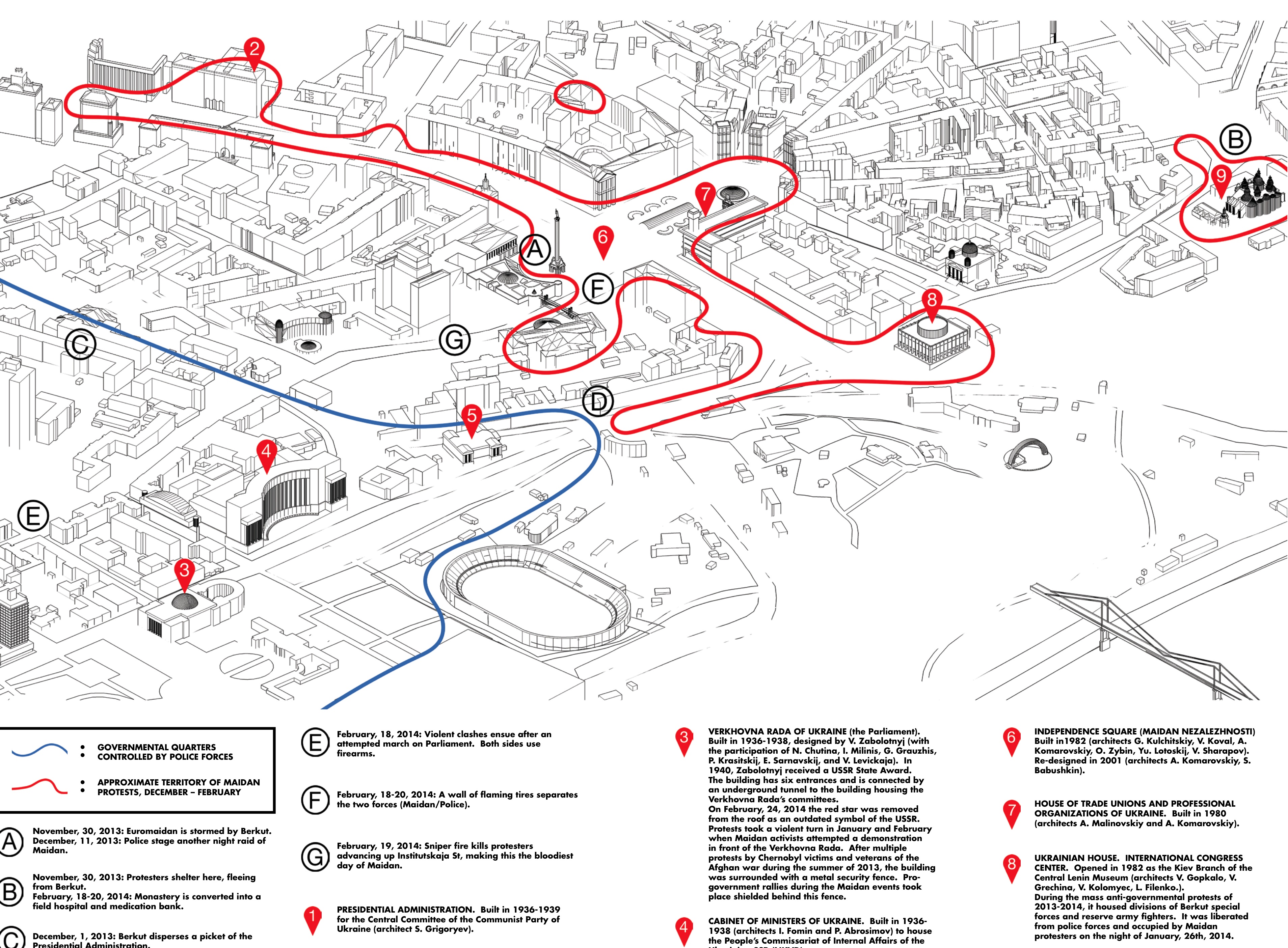

Neo-suprematist Zabolotnaya to this day has not acknowledged an act of censorship and did not officially apologize to the artists. But somehow, by some magic working in reverse, all things censored by her manicured hand sprung to life in Kiev in just a few months’ time, and a thousand real Molotov cocktails were thrown into the air during the Maidan protests of November, 2013-February, 2014. All came true: a ring of fire, an apocalyptic mood, a sense “of fighting the last battle,” and finally, the successful toppling and banishment of the tyrants if not directly to hell, then at least out of their cabinets. Mercedes, Peugeots, and the rest, now represented by a wall of burning tires. Even Zabolotnaya’s own monument to censorship – her black “square” (or rather, black rectangle), to which Kuznetsov’s scene of popular uprising, driven by an almost eschatological hope for the better, was reduced – reminds uncannily of the scorched blackness of Maidan after the battle of February 18-20, in which hundreds of civilians were killed and wounded by the President’s police forces.

I could not travel to Kiev while the events of the Maidan protests were taking place, and have no first-hand account of it. What I know is gathered from anxiously following the pulse of Facebook posts from friends and text messages from parents. The surface of spectacular images of riots, barricades, and wounded easily ossifies into something so cinematic that it becomes impossible to recognize the familiar streets behind this sheen.

Please forgive me, if this juxtaposition of two black cards (the censored panorama of popular indignation and a tarred square covered with flowers for the dead), in which I try to read the past and the future is too formal.

Burnt Maidan remains a degree zero, though. There is hope, made so much sharper by all the people who were willing to and did die for it, that it will become a foundational site of a less corrupt, less repressive, and less reactionary Ukraine.

The success of Maidan and the worth of all of the lives lost for its sake, as well as hopes, emotions, sleepless nights, and personal savings, are now threatened not only by internal enemies (bureaucrats, opportunists, rightwing conservatives, fascists, and bandits of all types), but also by external aggression from Putin’s Russia. And as the war propaganda and chauvinistic hysteria gain momentum, it becomes absolutely crucial to gather accounts and statements that help defray the erasure of experience. In the face of all the lies, the twisting of terms, the brutalizing simplification and bombast of the mass media, it falls to art, on both sides of the Russo-Ukrainian border, to do the work of nuancing, insisting on the complexity of history, memory, and responsibility. And the matter at hand is not at all to promote liberal all-inclusiveness, but to field an active defense of life from the violence of myths, and narrow binary oppositions invented with concrete political interests in mind.