Tom McCarthy’s new novel is attentive to the fibers of our social networks, but forgetful of its fleshy reader

Tom McCarthy, in his capacity as General Secretary of the semi-ironic art organization the International Necronautical Society, delivered a set of austere, art-serious dictums as part of their “Statement of Inauthenticity” in 2007. In these remarks, he riffs off of Rilke’s suggestion in Dunio Elegy Nine that:

Are we here, perhaps, for saying: house,

bridge, fountain, gate, jug, fruit-tree, window –

at most: column, tower......but for saying, realize,

oh, for a saying such as the things themselves would never

have profoundly said.

McCarthy and Co. sub in “cigarette…fruitbat…sponge,” repeating the last item twice more in the ordered style of a treatise, “(7.3) Sponge. (7.4) Sponge.”

He speaks for the sponge. But while Rilke wanted to put us in conversation with these objects to bring us into relation with the world, McCarthy just wants to put us in conversation with objects. “How do we let matter matter?” the manifesto asks.

In the work he has produced over the last decade, McCarthy has committed himself to the idea of fiction not as a sponge, but as a form of radio: something communicated, recirculated, in direct opposition to the romantic vision of it being inspired, proposed out of nothing and, at its best, set up in opposition to its culture. In his new novel Satin Island, McCarthy creates fiction that is so fluid that it’s hard to figure where the work ends and the culture it depicts begins.

McCarthy has already published at least one book about repetition, recirculation, and transmission. Remainder was first published independently in 2005 and propelled him to acclaim and mainstream publication in the US and UK in 2007. Remainder’s nameless narrator is hit on the head by some unspecific overhead debris. He uses his settlement money to recreate and rebuild everyday situations, chasing an aesthetic “tingling” of some nature. Something like authenticity, or singularity, or original experience — it’s never quite settled, and Remainder concludes in a kind of vaporous non-transcendence.

Remainder quickly earned a place as a leading example of a popular avant-garde novel. It was on the syllabus for at least one course of mine in college. Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York was rumored to have been ripped from McCarthy. And the book itself is being adapted to film later this year. Zadie Smith held up Remainder (next to Joseph O’Neill’s Netherland) as one of the “two paths” for the novel in the 21st century. Reading Satin Island, I can’t help but reflect on Smith’s piece, which now seems like a foundational document for reading and understanding contemporary English language fiction.

But I wonder too if Smith’s diagnosis of Netherland’s “lyrical realism” and her heralding of Remainder’s bold avant-ness hasn’t reversed itself. Netherland, Smith claimed, was a perfect sort of novel, while Remainder, in its repetition, was singular. Today Satin Island feels quite perfect, but perfect in the way an uncanny piece of CGI is — lifelike but lifeless, less a piece of art than something with the aura of a version.

McCarthy has made hay of his vanguard position within the Anglo-American scene. A staunch anti-realist (even a kind of “anti-humanist”), he prefers to foreground the shared, the networked. Social architecture before individual psychology, and always the dispersal of meaning over our contact with it. He is also upfront about his own emergence from avant-garde British art traditions and the French nouveau roman as practiced by writers like Alain Robbe-Grillet, Marguerite Duras, later Jean-Phillipe Touissant, preempted in the English scene by Beckett, then echoed by J.G. Ballard, with Don DeLillo its closest American inheritor. McCarthy really does seem perfectly in line with this tradition, but this means his writing, too, begins to feel more and more like part of a historical avant-garde than one that operates in the present tense.

One of the more visible debates in contemporary fiction is the now-routine one between the poles of artifice and authenticity, irony and sincerity, realism and whatever the opposite of realism is, etc. McCarthy gets major credit for being a perceptive critic of one “side” of these conversations: he is vicious toward the cult of authenticity, the kind of status quo fiction honored with national awards, taught in MFA programs, and lauded with proclamations like “Great American Novel.” His disdain for this style (the “lyrical realism” Smith names) is real and necessary. His disposal of traditional fictional architecture is daring. He sacrifices, almost entirely here, recognizable characters, narrative stakes, rising action, all the elemental stuff that supposedly make a novel. But it’s always hard to fully endorse something that isn’t designed, primarily, for real live human readers, but instead systems of analysis. A sugar rope fed through a machine is winnowed down to almost nothing, then a perfectly formed cane, or a droplet, or a taffy pod that tastes sugary at first, but the flavor fades, and only raw substance is left over.

Satin Island reads like an extension of certain ideas in Remainder and his follow up, C.. A lightly- etched protagonist known only by the initial “U.” is a trained anthropologist working for a giant, zeitgeisty consulting firm. Or something like a consulting firm. The narrative relies in large part on our recognition of the unspecificity of this kind of work. U.’s company takes on a big, international account known as the “Koob Sassen Project,” the contents and character of which aren’t clear, but of which our narrator notes:

The project was important. It will have direct effects on you; in fact there’s probably not a single area of your daily life that it hasn’t in some way or another, touched on, penetrated, changed; although you probably don’t know this.

“Network architecture” is how one colleague characterizes it. Satin Island concerns itself with exactly this. The skeleton and underpinnings of a networked culture. The connective tissue of events or themes or memes are U.’s domain. He is paid to observe human behavior, but mostly he just recycles continental philosophy and academic theory into reports and talks for his boss, a mysterious man named Peyman, to deliver, TED-style, around the world. Even the wildest continental theory, the most radical left-wing philosophy, whatever, can boil down easily enough into a banal Silicon Valley slogan.

It’s true, “disruption” is the watchword of prophets Zuckerberg and Žižek alike, and part of McCarthy’s gambit with this book is to cast these vocabularies as, in some sense, complementary. He does a fine job of imitating this prose style, couching things in appealing, allusive, occasionally cute terms — his first report for The Company used Lévi-Strauss to analyze Levis (Straus) jeans, and works with Deleuze’s concept of le pli, the pleat, to deconstruct blue jeans semiotics.

This pretty much set the protocol or MO I’d deploy in my work for the Company from then on in: feeding vanguard theory, almost always from the left side of the spectrum, back into the corporate machine. The machine could swallow everything, incorporate it seamlessly…

The same could be said of the position of the avant-garde novel, an object McCarthy wants badly to weaponize in a way that escapes the warp and weft of culture-making. But a constant “revolutionizing” of technology, of consumer identity, the tailoring of our exact pleats and rips to stand in for our singularity as humanist subjects, seems to make something like that impossible. This is the uneasy grid U. finds himself embedded in; any attempt at “true” disruption of the prevailing logic is now an extension of that logic.

His is an utterly modern form of labor, whatever it is, with unclear implications. There’s rather a lot of literary potential in this: The problem is that McCarthy doesn’t give us a sense of possibility to an agent’s position within a grid or system. In fact, no recent author of this new breed of novel has quite been able to. I say breed because McCarthy has written another iteration of the modern clerk novel. We’ve seen a lot of these contemporary Bartlebys lately: Dave Eggers wrote two variations, Joseph O’Neill had The Dog last year, Teju Cole’s Open City introduced the hospital-resident-clerk, Joshua Cohen’s take on the form comes out this summer. David Foster Wallace’s unfinished The Pale King set a precedent.

These books usually feature ponderous, passive, male protagonists in clerical or otherwise obscure roles at larger, more mysterious conglomerates, tech or finance or the IRS, whatever the case may be. Quietly and at their leisure they deconstruct their own corporate surroundings, prodding at the stitchings of their personal identity onto the corporate body. Trying to find a seam.

The clerk novel seems like a fair and timely genre. It acknowledges, first, that we are all subject to systems not of our own making, the corporate structure not only of business, but of civic society, the culture industry, our social networks. “Corporate” as in embodied, made up, aggregated. It rejects the idea of the solitary, romantic holdout, and asks the rather more practical, grounded, truthful (!) question: What do we do from where we are?

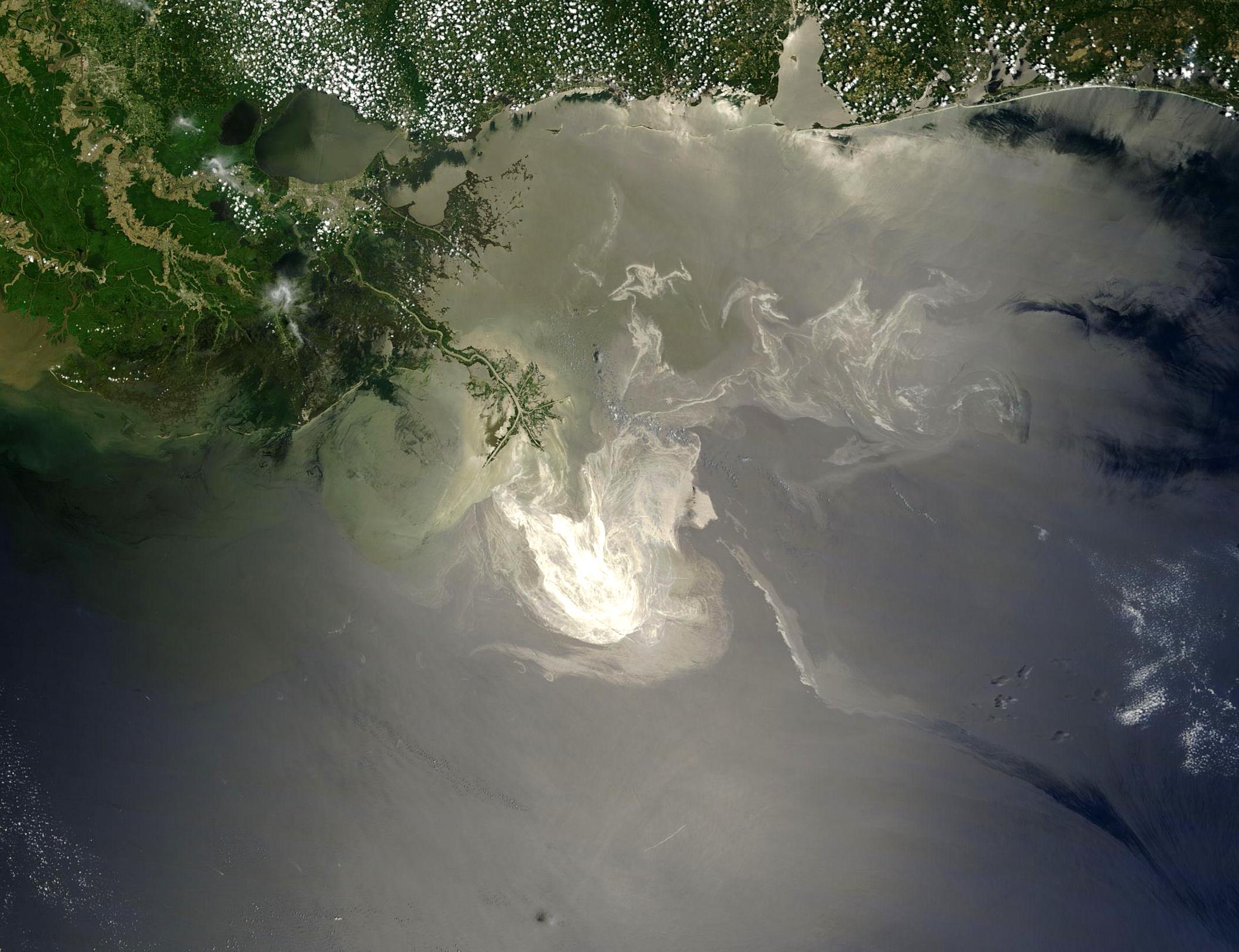

But U. sees this clerk position as more of an art gesture than an operable political or personal one. He thinks of himself a “meaning maker,” a nocturnal worker like bakers or milkmen whose product is immanent, but whose presence is transcendent. He is sure that his construction of “dossiers” (on parachuting deaths, oil spills, jellyfish) will conspire to create some kind of grand narrative. He is working on an ethnographic opus he calls “the Work,” or “The Great Report,” a master document that captures the whole of the contemporary. It is never completed, of course, always amorphously “finding its form.”

This search for the “the Work” quickly veers off into a form of blog-like curation. Tagging. #TheDossier. He arranges objects and events the way you can see them on any number of popular, pseudo-political Tumblrs. Images cycle by and refresh, ad infinitum: a fancy single speed bike, the new Apple product, Angela Davis raising her fist, a clip from a Bergman film, a pristine pair of Nikes, an animal .gif, a quote from Walter Benjamin, a Warhol, porn, a black and white photo of some terrible war atrocity. U. notes somewhere along the way that “An anthropologist’s not interested in singularities, but in generics.” This serves as a kind of mission statement for the rest of the book, which consists of his intellectual wanderings, occasional sex with a woman named Madison, and the slow death of one of his colleagues from cancer.

Sometimes McCarthy has the writerly abilities to do some amazing lyrical, attentive, Knausgaard-like maneuver, for instance when the narrator recalls seeing taffy being made in a San Francisco confectionary as a child:

I’d stood rooted to the pavement in front of a candy-store window in which taffy was being pulled, transfixed by the contortions of the huge, unmanageable lump (what child could eat all that?) as the machine’s arms plied it, its endless metamorphoses in which, despite the regular, repeating movements that stretched and folded, stretched and slapped the taffy through the same shapes over and over again, I knew even then, that no part of it, no molecule, would ever occupy the same spot in the overall formation twice.

There is something important (or at least daring) about showing that you can do all that, and then turning your nose up at it. McCarthy likes to pull the rug out from under unsuspecting readers, lulling us into a madeleine moment, then draining it of its pathos as we get lost in its physicality, its non-humanity. We can never decide if the narrator has fully absorbed the “cultural logic” of contemporary capitalism or if he is working as a kind of agent within it. Maybe this is a simplistic opposition, one that he navigates with the undecidability it implies. He imagines the creation of a new anthropology, and the awards and honors it will bring him:

I imagined cells of clandestine new-ethnographic operators doing strange things in deliberate, strategic ways, like those conceptual artists in the sixties who made careers out of following strangers…Could that kind of stuff, that kind of practice, be applied to modern life?

For McCarthy “authenticity” is the ideological sidekick for a kind of identity-based consumptive capitalism, but does this mean we have to sacrifice recognizable human qualities for a repetitive demonstration of the ideological? I think he deserves credit for saying, or staking that fiction shouldn’t have to do with some kind of original, singular self-expression of the authentic, but such a gambit means that books like Remainder or Satin Island really do work better as treatises or manifestos than as novels.

The “problem” is that Satin Island is so utterly enjoyable. It’s a perfect kind of book. It has the internal consistency and air-tightness of a good manifesto. Catnip for the liberal arts graduate, the dilettante philosopher, the disgruntled culture worker. It goes down so easy. Is it wrong to criticize a book for being so perfectly itself? If you think this unfair, then Satin Island really is the perfection of a form, an expertly produced confection. At the same time, that perfection can be terminal.

Books, not kinds of books, hold our attention, just as people, not kinds of people enrich our lives. Like Zadie Smith says in her assessment of O’Neill’s Netherland,

…our receptive pathways are so solidly established that to read this novel is to feel a powerful, somewhat dispiriting sense of recognition. It seems perfectly done—in a sense that’s the problem.

Before long, you begin to feel like those rats hitting the dopamine levers connected by node to their brains. Like McCarthy’s narrator in Remainder, the reader has become involved in the indulgent project of recreating enigmatically appealing aesthetic scenarios. And so reading Satin Island kind of becomes an exercise in tempering one’s enjoyment of it with certain broader questions. Who is this for? What does it do, serviceably? What parts of me does this activate?

McCarthy seems to so favor the “networked” or “shared” to the singular that the work begins to flatter itself as the kind of fiction a “sharing economy” requires — or deserves. An ecosystem of literature that operates as a kind of data plan, a “platform” of experience. Content’s instantaneous and universal availability might manifest its discontent in the yearning for the authentic the lyrical realist novels deal in. Or it might, as it does here, manifest in an aesthetic overinvestment in the very dreary, inhuman OK Computer universe of “late capitalism” it supposedly inveighs against.

Smith credited Remainder with doing a kind of “constructive deconstruction,” a good spring cleaning away of lyrical realism’s cobwebs. Now we’re left with that old problem of what to build next.