A first-class in-flight magazine makes you feel like you belong in the sky

I first heard about Rhapsody magazine from a New York Times article touting its high profile writers: Joyce Carol Oates, Karen Russell, Emily St. John Mandel, and so on. The noteworthy thing about Rhapsody, for the purposes of that article, was that it wasn’t just any magazine, it was an in-flight magazine. And not just any in-flight magazine, either. Rhapsody is reserved for first class passengers on United Airlines flights. This is airplane reading, rarified.

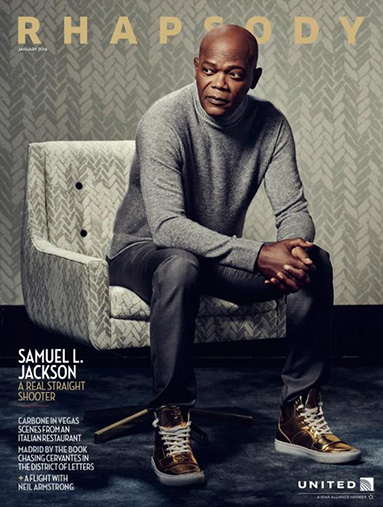

I wanted to track down this publication in order to see how it merged literariness with the privileges of first class air travel. As I do not fly United Airlines regularly—and when I do, I’m not in first class—I assumed I would have to sweet-talk a United gate representative into smuggling a copy out of a waiting airliner and to me. I had the scenario all worked out in my head. On a whim I Googled the magazine, the results of which shattered my fantasy. There it was, Rhapsody, all issues available for download in tidy thumbnail form, no first class itinerary required. That was anticlimactic. I downloaded the most recent issue, January 2016, Samuel L. Jackson chilling on the cover in silver high-top sneakers, the United logo directly under the sole of his left foot.

What is an in-flight magazine? Not Rhapsody, but a regular in-flight magazine, like Hemispheres or Delta’s Sky. Some unifying features come to mind: an introductory note from the CEO stressing the airline’s progress, challenges, and opportunities that lie ahead. Full-page ads for button-down shirts meant to be kept untucked. Articles featuring destination cities and glamour shots of blonde, beaming sales representatives beckoning readers to join a dating service based around the mid-day meal, and testimonials evincing true love finally found. Promotions for the airline’s loyalty program, promising perks for joining their family. Route maps toward the back, in addition to beverage lists, aircraft models and stats, and simplified airport diagrams for major hubs.

Throughout, the normal in-flight magazine reminds me that I am participating in air travel, and encourages me to repeat this activity—to make it more and more a part of my everyday life. If there is something like a perspective of the in-flight magazine, it may be that in these pages is the whole world, poured out glittering, airborne, and replete with everything I need for survival, sustenance, and success.

But Rhapsody is nothing like that.

The magazine is, perhaps not surprisingly, comprised mostly of advertisements: for high-end apparel, luxury items, and hotels. Occasionally a more plebeian object appears, like in a Colavita olive oil ad, which almost reflexively states “Think Outside the Bottle.” If the first-class cabin is a box of sorts, what would it mean to think outside of it? Is there room in this in-flight magazine for critical reflection, or is this medium a predictable product of its own class-based constraints?

There is a wristwatch for sale that is roughly the amount of my entire home mortgage. (The Graff Mastergraff Ultra Flat Icon Skeleton 43 mm., $211,000) In an exclusive interview, Samuel L. Jackson expounds on his choice to star in the movie Snakes on a Plane: “I was like, Hell yeah—I want to see this movie, and I want to see me in it.’” A brief article about the McLaren 570S sports car states, nonchalantly, “A car with technology like this, for under $200,000, is a steal.” That amount, $200,000, keeps coming up like it’s pocket change—perhaps subtly making first class fare seem not so expensive, after all.

The maximalist language of luxury accumulates over the course of the ads:

"The World’s Most Innovative Luggage Has Arrived"—T.R.S. Ballistic “self-balancing”

“Quite simply, the world’s finest fire pit & grill”—Cowboy Cauldron

But then there are more simple and fairly palatable pieces, like the one-page feature on the Italian appetizer staple, melon and prosciutto. The basic message is how good food can involve quality ingredients, and fewer of them at that. The final piece in the magazine is a short personal narrative by Mark Vanhoenacker (pilot-author of the recent bestseller Skyfaring), recalling the time Neil Armstrong was a passenger on one of his flights, waxing positive about views from above, linking space rockets and airliners by the aerial visions they afford.

The Vanhoenacker piece is part of a series of features called “Plane Spoken,” penned by authors of the moment, each somehow or another relating to flight. This is where the aforementioned A-list authors normally appear. But while the New York Times article made it sound like Rhapsody featured literary writing throughout, it turns out that this “high minded” content is given a single page—namely, the last page of the magazine.

Here’s the funny thing about Rhapsody, finally: There’s very little in it, at all, that lets you know it’s an in-flight magazine. There is the United logo on the front cover, and there are two “Fly the Friendly Skies” advertisements within the pages, but otherwise there is nothing about air travel, or the fact that you are (or should be) sitting in a jetliner while you read it. In many ways Rhapsody is the obverse of a normal in-flight magazine, subsuming all the aviation iconography and airline branding under the far more aggressive campaign of luxury living. Human air travel is normalized not through excessive denotation, but through a kind of connotative understatement, wherein a certain standard of life is suggested to be naturally contiguous with first class flight.

The “Plane Spoken” column with its theme of flight seems to stand in contrast to most of the magazine—which barely announces its status as airplane reading. This is air travel refined, meditated upon self-reflexively, as if already accepted to be as natural as breathing. And not only flight, but a set of property relations in tow. Wealth and flight are deemed duly natural in these pages. Rhapsody is no mere in-flight magazine, and not just because it contains the works of bestselling authors. It posits the nature of flight and the history of class struggle as coterminous, calmly in balance. Rhapsody displays progress as if at cruising altitude, entirely on course.