This conversation took place in a busy café in Ridgewood, Queens, where we talked about the AEMP’s “countercartography” work: the use of mapping technologies to aid tenant struggles against displacement. We also discussed the YIMBY (“Yes in My Backyard”) movement, a pro-growth formation that originated in the San Francisco Bay Area and has recently taken hold in cities nationwide (including, to a much lesser extent, New York). YIMBYs embrace the increased construction of market-rate apartments as a solution to the housing crisis. The YIMBYs conflate opponents of market-rate and luxury housing—including working-class and POC tenant groups—with NIMBY (“Not in My Backyard”), a term generally referring to obstructionist, exclusionary, and usually white homeowners opposed to things like homeless shelters and multifamily housing in their neighborhoods. McElroy rejects both NIMBY and YIMBY, and refers to the latter group’s approach as “all housing matters.” As our discussion turned to the role of technology and tech firms in driving displacement, we were interrupted by patrons plugging in laptops beneath our table.

•

RICO CLEFFI.— What is the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project?

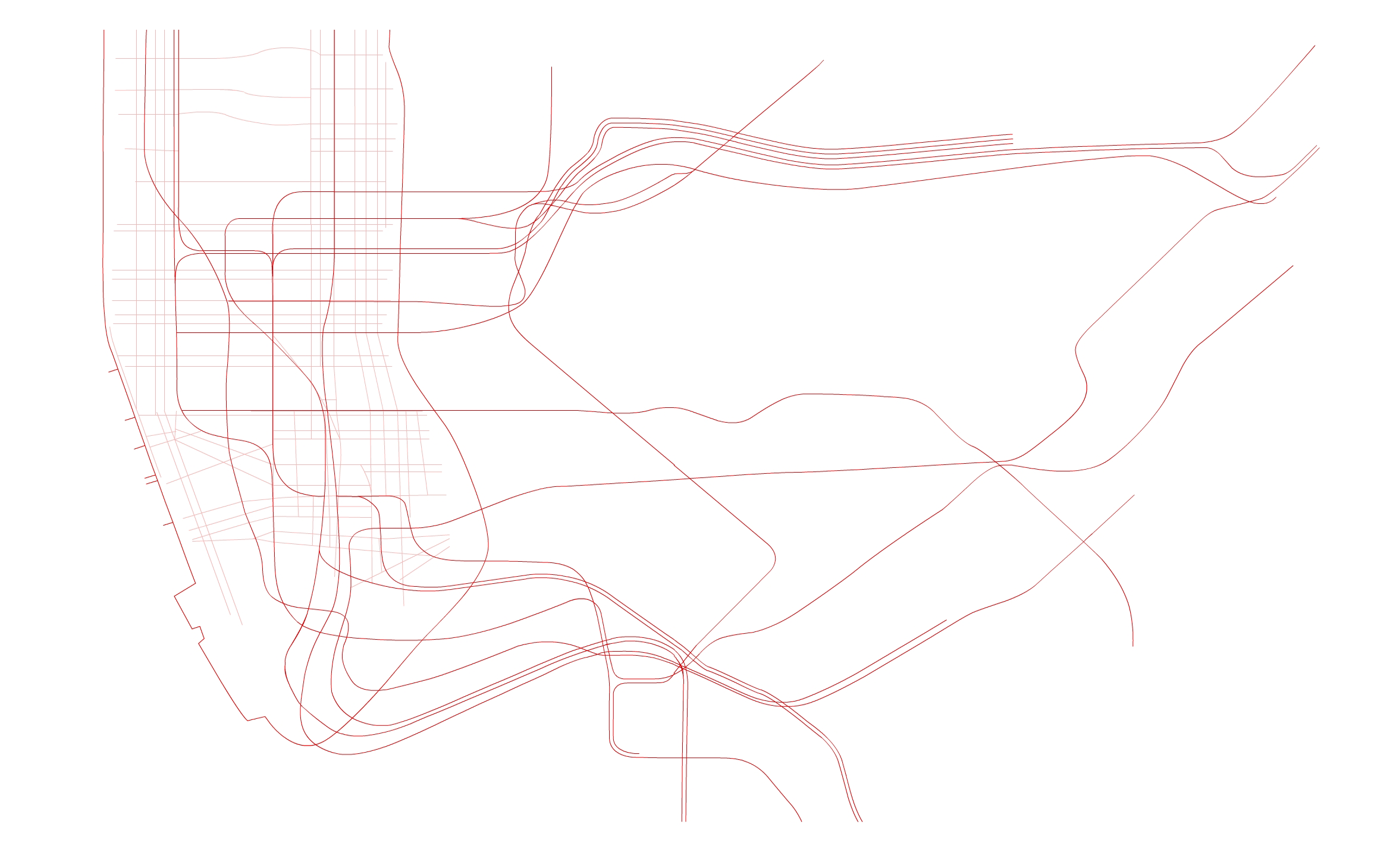

ERIN McELROY.— It’s an activist collective working with digital cartography and oral-history narrative that’s been producing data, maps, and stories to amplify housing-justice struggles in the San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles, and New York City. I helped start the project in San Francisco in 2013, and it’s since expanded in region and scope.

What sort of patterns have you noticed since you started? Are you seeing more evictions?

We started the project in the beginning of the era that people are now calling the tech boom 2.0, or the second dot-com boom, which a lot of people date beginning in 2010 or 2011. It follows the dot-com boom of the late ’90s and early 2000s, as well as the financial recession. This period began where a lot of wealth started accumulating in the Bay Area and Silicon Valley. Real-estate speculators took advantage in different cities differentially, resulting in heightened evictions and the displacement of mostly poor and working-class communities of color. That’s the general trend.

Do you have any idea of the number of evictions?

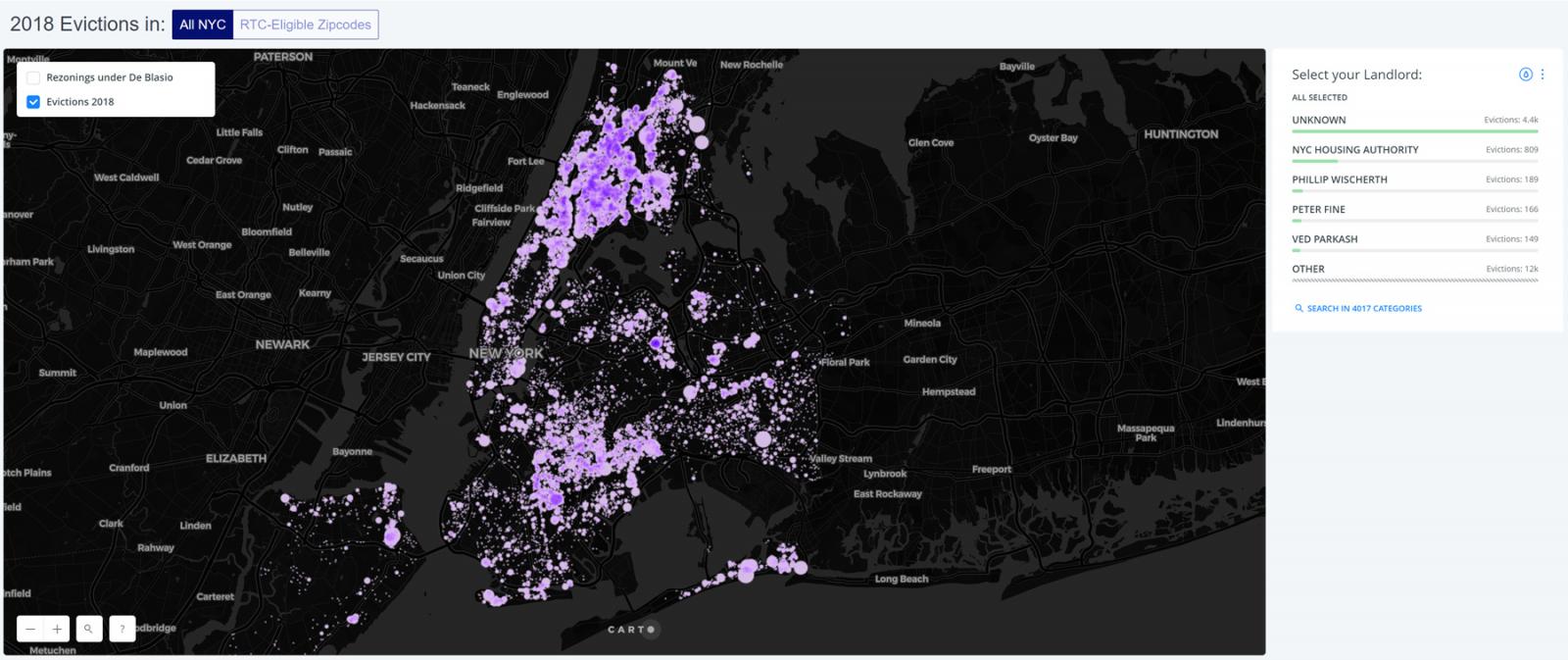

What we have is eviction data from the rent boards in San Francisco and Oakland, and we have court data for the whole region. We have different sets of data for Los Angeles and New York City. But no matter how much official data we get, we can never actually figure out how many people are leaving when their rents go up, forcing them to leave. We do record cases of harassment, but we can never get the full scope of how many people are being pushed out. A lot of people who are undocumented are being harassed out or pushed out by landlords. Not all of that makes its way into our data, or is recorded.

Just looking at your maps, it’s staggering. It’s got to be thousands of evictions.

Yeah, tens of thousands.

Here in New York, I probably know dozens of people who have moved just because their apartment stopped being rent stabilized or they were hit with a rent increase they couldn’t pay—people who moved long before things got to the eviction stage.

In San Francisco beginning in 2015, buyouts began to be recorded by the city. That’s when the landlord says, “I’m going to evict you, and you’re going to have to go through this whole court procedure with me, or I’m going to give you maybe $10,000 under the table.” That’s been going on for a long time. But housing organizations pressured the city to mandate that those sorts of transactions be recorded and registered. So we’ve been getting concrete data on those, and there’s a huge number. Yet we’re still probably not getting even half of what is actually going on in terms of those sort of bribes or buyouts. And that’s just in San Francisco. Buyouts aren’t recorded in most cities—and those aren’t technically counted as “evictions.” A lot of people don’t want to go through court procedures if they don’t have to.

What can you learn from a city by looking at its evictions?

You can look at what neighborhoods are being hit the hardest by real-estate speculation. You can start to understand who’s being displaced. We look at evictions holistically—whether in Oakland or San Francisco or San Jose, or wherever we’re working—to figure out which neighborhoods have the highest rates.

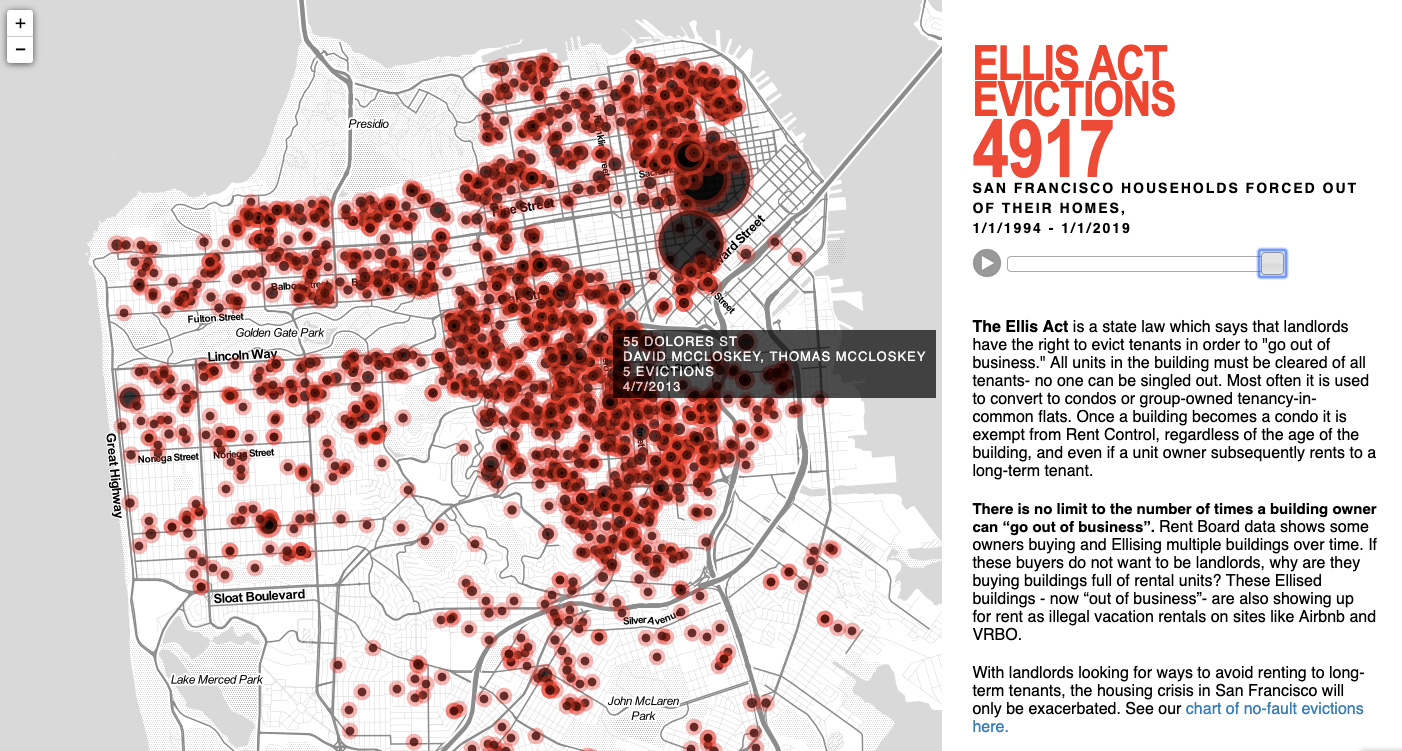

There are different kinds of evictions. Especially in cities with rent control or rent stabilization, there are generally “fault” evictions and “no-fault” evictions. No-fault evictions happen when tenants have done nothing wrong. They’re paying the rent on time, don’t break their lease, and are still evicted. And then there are fault evictions when somebody breaks a lease and they are evicted, though we are careful not to pathologize this latter category, as often fault evictions are highly racialized and class-based. We’ve been seeing both categories of eviction go up. Many are being enacted by LLCs [Limited Liability Companies] and shell companies. We do a lot of research to figure out who owns these LLCs and what kind of financial webs they’re a part of.

In San Francisco, for instance, there might be tenants on one street being evicted by 55 Dolores Street LLC, and on the next block some tenants are being evicted by 49 Guerrero Street LLC. They might not know that there’s some big investment company, Urban Green Investments, who owns not only those two shell companies but also a bunch of other ones; suddenly this investment company is evicting tenants all over the city through generic-sounding LLCs. We do a lot of research to figure out who the actual evictors are and what points of pressure can be activated by people on the ground to pressure landlords into rescinding the evictions. So, we learn a lot about the process of financialization [outside investors (mainly private equity firms) purchasing property]—which has changed quite a bit in the last 10 years. We’ve also learned a lot about infrastructure that correlates with eviction rates. For instance, in San Francisco, we’ve seen evictions spike around Google bus stops, or tech bus stops that private tech companies use to shuttle their workers to and from their Silicon Valley campuses.

Are you seeing the same shell companies over and over again?

What we’re seeing is the same landlords or investors. We won’t see the same shell company, but we’ll see the same person or investor behind the shell companies. There’s this company called Veritas. They’re the biggest landlord in San Francisco right now, and have been behind brutal evictions. Tenants in Veritas buildings have been conducting their own research and organizing together to apply pressure on Veritas. There’s a group in New York called Just Fix NYC who the NYC AEMP chapter partners with, and they’re doing similar research in a really exciting way.

The developers, the private-equity companies, they’re using maps and cartography, right? They aren’t random at all—they are very strategic in selecting locations.

Yeah. And of course there’s the phenomenon of realtors rebranding neighborhoods or parts of neighborhoods to make them more desirable for the new gentry. There’s this real-estate speculator, Jennifer Rosdail, who has rebranded part of the Mission in San Francisco as “the Quad.” So suddenly it becomes not the Mission, a Latinx, working-class neighborhood, but this other place for techies. And next a bunch of Google bus stops are placed within it. We found that 69 percent of no-fault evictions occur within four blocks of these bus stops. Cartography, geography, et cetera, have historically been sciences of colonization. And that endures, especially in terms of cartographies of real-estate rebranding, speculation, and infrastructure. This is why we describe our work as aligned with countercartography.

And you’re using these same technologies as the landlords to subvert capital. Some of the coverage of the AEMP has had this tone of bemusement that you are not using your talents and your brains for “legit” purposes, i.e. to make money.

Yeah, it’s like you’re supposed to start a project, get some capital, sell it to somebody else, and be done with it in two years. That’s the startup idea—it’s just embedded into the fabric of the city. We’re not a startup—we’re just activists. Our endgame is not to make money. Our endgame is to be made obsolete, because we want evictions to be obsolete.

Are you seeing many victories on a micro level?

Sure. Many housing groups have been successful in stopping evictions by simply figuring out who the LLCs are, and where their headquarters are. This is a good example: A friend of mine, Benito, was in his midsixties when his building was sold to Pineapple Boy LLC. Benito didn’t know who Pineapple Boy LLC was, or where they were located. So, we started doing research and found out it is actually the shell company for someone named Michael Harrison who cofounded Vanguard Properties, located right in the Mission.

And on four separate occasions, we went into this real-estate company’s offices to hold demonstrations, always being kicked out. On the fourth time, they kicked us out so violently that they feared legal retaliation, and withdrew the eviction. We didn’t even have to go through any court procedure. It was just research and direct action, and resulted in Benito not being evicted. It was a four-unit building—everybody there was able to stay. Then, of course the building went back on the market, and we said, “Okay, is this going to happen again, is another speculator going to come in?” So, we worked with the San Francisco Community Land Trust to buy the building. Now the Land Trust owns the building, and Benito has a 99-year lease, as do the other tenants in the building. It’s sort of a complete victory. The building’s off the market, and nobody’s being evicted. The speculator didn’t make any money off it. Now it may be more difficult for Harrison to use shell companies in the future, because we’re looking at what he’s doing.

There’s a new victory in San Francisco, the right to counsel that was just passed. Now anybody getting evicted is entitled to a lawyer. That’s really exciting. There are a lot of good legislative and policy things that have happened. Evictions are still accumulating, but so is the anti-eviction movement’s momentum.

What is the YIMBY movement, and how have they been an impediment to social change?

YIMBY stands for “Yes in My Backyard,” and it came to be around 2014, shortly after we started as a project. Its founder, Sonja Trauss, first started this group called literally BARF. I think there was sort of a hipster irony she had going for her. It stands for the Bay Area Renters Federation, but some of the people that were most powerful in BARF were not renters. I think from the beginning you can see with the name BARF there’s this sort of co-option of language and ideas that I think is very endemic to the YIMBY movement. They now are a movement, and almost a political party—not quite. But there are a number of groups and politicians that identify as YIMBY. And they deceptively position their enemy as NIMBY, “Not in My Backyard,” a term which of course goes back decades, referencing mostly white homeowners trying to protect the value of their properties from “undesirables,” whether that was people with disabilities, people of color, or anyone who threatens the white heteronormative property-owning household. YIMBYs conflate NIMBY homeowners with those opposing luxury and market-rate development.

YIMBYs believe that they can solve the housing crisis by developing more housing. To them, it doesn’t matter what kind of housing is built, whether it’s market rate, luxury, or affordable. But the big problem is, as we’ve found—and not just us, a lot of other housing-justice organizations have found this too—unless you’re building at least around 60 percent below-market-rate and low-income housing, you’re not doing anything other than maintaining the status quo. That said, we don’t want even 1% of new development to be market-rate or luxury, and even most "affordable housing" is not affordable.

Of course, developers are being fed by capital, and they’re capitalist by nature. They’re not trying to build 60 percent, 70 percent, 80 percent low-income housing. They’re trying to build 20 percent at most. So, with each new development project, what we’re seeing is an increase of luxury and market-rate housing catering towards the wealthy. The YIMBYs embody the cult of disruption that I think characterizes big tech in general. They like to come to planning and housing meetings, acting elitist, as if they know what’s going on.

When they started, I think because they were called BARF, we thought they were joking. We said, “Just ignore them. They’ll go away. We won’t even give them attention. It’s not worth it.” But they’ve obviously grown. I’m still hoping that they’ll go away.

And one of their tactics is to brand the people fighting actual displacement as the problem?

Yeah, NIMBY. So, they’ll brand me as NIMBY, even though I work against NIMBYism. The world isn’t just YIMBY or NIMBY, but they want that to be the case, because it makes it easy for them to market themselves as the solution. Most people involved in the housing-justice movement consider both NIMBY and YIMBY the problem. But YIMBYs like to just portray the world as either NIMBY or YIMBY, and then equate white wealthy homeowners with tenants (many of whom are people of color) fighting against evictions. Which is ridiculous.

Even though YIMBY really hasn’t taken off in NYC yet, the ideology has been gaining traction. And one of the things they do is to totally disregard established tenant organizations as being out of touch and resistant to change.

In San Francisco you can trace the housing-justice movement to different origins. There was the I-Hotel fight, led mostly by Asian immigrant tenants in the late ’60s, early ’70s—which helped engender other organizing campaigns for rent control and against condoization. San Francisco Tenants Union started around that time. The Housing Rights Committee, Causa Justa Just Cause, and other groups have been doing important work for decades too. So, there are long-standing tenant organizations that have been working with and against politicians, working to basically protect renters for a long time. And then you have YIMBY groups who come along and think that they know better than the groups that have been really embedded in the community for a long time. Of course, the AEMP is also a new group, but by being located within the Tenant’s Union and part of coalitions, we are always deferring to people who have been doing this work for a long time. We’re not trying to step on toes. But the YIMBYs are coming in very much like Airbnb or Uber, companies that just want to disrupt business as usual and who think that they have the knowledge to do things better.

One thing I keep seeing from YIMBY leaders is this idea that the city should be “for everyone,” not just people who live there now. Are they talking about migrants or refugees or are they talking about their wealthy friends?

They’re talking about their wealthy friends. They’re definitely not talking about people moving in to escape economic or social oppression. That’s why we started trying to think of them as people who think “all housing matters.”

That’s a great term—did you coin that?

We thought that it was just the easiest way to describe what they’re saying in terms of housing.

And they generally don’t support rent-control or rent-stabilization legislation?

Not as a movement. They’re just looking at development.

One of the things I really noticed in San Francisco—you really feel a distance between the tech people and everyone else, right? It’s really pronounced.

You could just land from outer space and have no context about what’s going on and feel it right away. It’s very divided. I remember that when blockades against the Google buses began, a lot of tech workers got defensive. There was this French journalist—for some reason there was a lot of interest in what was happening by foreign journalists all of a sudden—who had been reporting for 40 years, and she said she had never had a harder time accessing people to talk to than in the tech industry. She said it was harder here than when she was reporting in Moscow in the eighties.

Do they engage with you at protests? Are there hecklers?

There’s often one or two hecklers. But I don’t think they are political in nature. There’s a lot of avoidance; people have their headphones on; they don’t want to engage. It’s weird. And it changes the city. Suddenly new restaurants go up, catering towards them. Shops catering towards those being evicted lose their clientele as their rents also go up, and then they vanish.

We’ve talked about the backward forces. What struggles inspire you right now?

I’m excited about the ways that we can form new alliances to fight global capital, but from this really local context. So, with Amazon coming to New York [now it’s gone, thanks to organizing], or Google to Berlin and San Jose—how do we think about building new kinds of international solidarity, coming out of the anti-globalization movement, but really rooted in local struggles? I spent a little bit of time in Berlin last year. I’m learning a lot from the folks fighting Google there, and who, in many ways, have been successful. Their actions were done in solidarity with the anti-Google people in San Jose and Toronto, where Google is setting up campuses.

One critique I’ve encountered is the best thing for San Francisco would have been maybe not allowing these companies to accrue so much power in the first place.

Yeah, we want to abolish these companies. We don’t want Google to exist, whether it’s because of its gentrifying effects, or because of its military technology, or data colonization, but unfortunately we’re still very dependent on it. And I think there’s a lot of work to be done in trying to get ourselves off of these platforms. But that also takes a lot of work, and when people are working 14-hour days, they don’t necessarily have time to say, “How can I get myself off Google?” That’s an area we need to grow as a community.

I think it’s important to have a decentralized movement that looks at the various effects of these techno-capitalist entanglements, and that fights them in different ways, with different capacities, depending on what makes sense. It’s also important for people to build alliances between movements, which is something I found inspiring in Berlin; people are trying to create a new search engine to get off Google, but are also fighting Google’s gentrifying effects, while maintaining international solidarity.